Twos company: Bill Farrimond and Hopper Levett

A rare duo of wicketkeepers for whom seconds were plenty

Paul Edwards

Jul 7, 2020, 9:51 AM

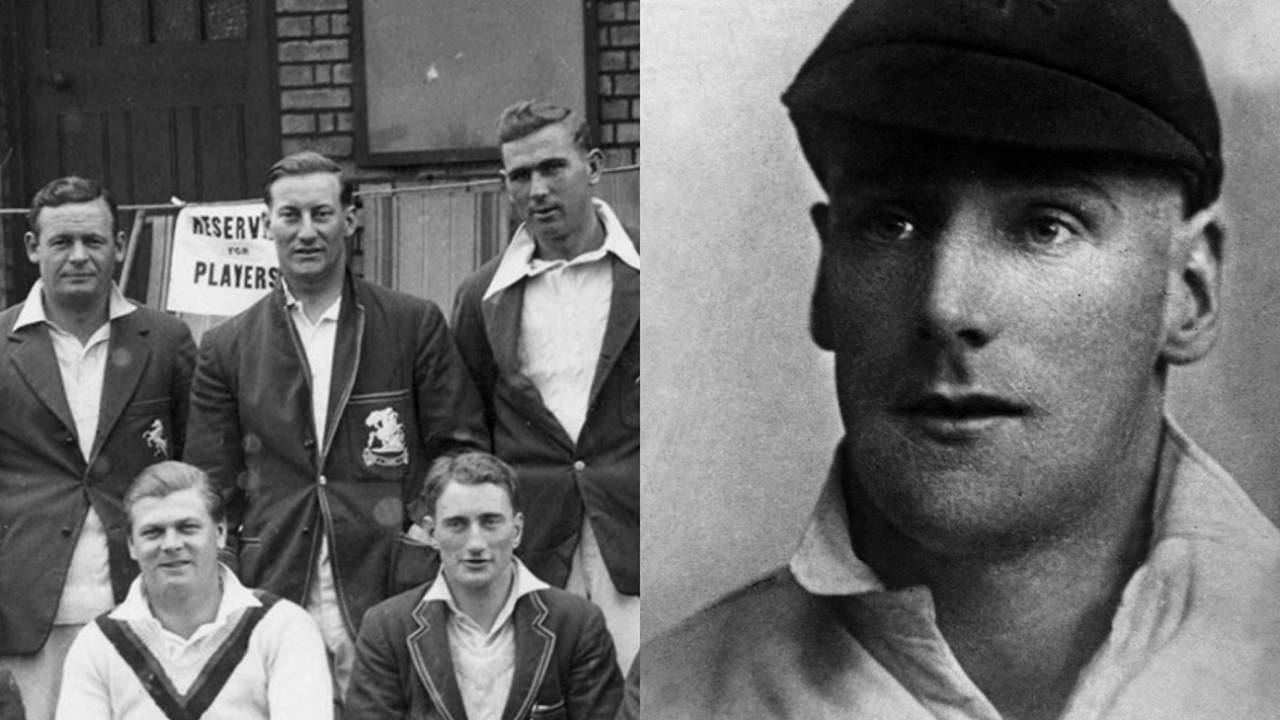

Hopper Levett (left image, top row, middle) and Bill Farrimond (right image) • Getty Images

In the 1930s you would have done well to find two more contented cricketers in England than Bill Farrimond of Lancashire and "Hopper" Levett of Kent. Both were second-choice county wicketkeepers.

Immediately the modern player recoils in disbelief. Surely nobody can ever have been satisfied with life in the twos. Current coaches are always reminding their charges that promising talents must break into the first team after a couple of seasons on a professional staff. Absolutely no one spends his career in the seconds. Except, of course, that Farrimond did more or less precisely that.

In Lancashire's five title-winning seasons he played just 17 championship games, ten of them in 1930 when George Duckworth was in the England team. Yet while Duckworth was always preferred to Farrimond and Les Ames' ability with both gauntlets and bat sometimes restricted Levett's appearances for Kent, the two deputies won Test caps and Farrimond twice played alongside Ames for England.

ALSO READ: Young George Cox, who made Hove his garden

But although Levett and Farrimond are cited as examples of deeply loyal cricketers whose exceptional skills would have made them first-team regulars at other counties their careers followed rather different trajectories. For one thing William Howard Vincent Levett was an amateur whose family involvement in hop-growing gave him both a nickname and relative freedom as regards a chosen career. That last matter was quickly settled.

Born in Goudhurst, he remained with Kent from his debut in 1930 until his retirement in 1947 and became one of the most widely respected and best-loved men in the history of his county's cricket. The authors of Kent: 100 Greats record that, "He would talk to anyone about cricket or life, regardless of age, social status, sex, creed, occupation, state of mind or anything else and without always bothering to finish one sentence before starting the next."

Many of those to whom Levett chatted when he was president of both Kent and its supporters' club will have recalled the high-quality wicketkeeping that earned him 477 victims, 195 of them (40.88%) stumpings. (Farrimond's percentage was 24.09, which is still high and he played half his games on softer, greener Lancashire pitches.)

The presence of AP "Tich" Freeman and Doug Wright in the Kent side helps to explain Levett's statistics and a ratio that would amaze most contemporary keepers. In the years 1933-35 he stumped more batsmen than he caught and his availability was plainly valuable to the county on the frequent occasions when Ames wanted to concentrate on his batting or when back problems prevented him taking the gloves.

Hopper Levett (with gloves) follows Alfred 'Tich' Freeman onto the field as part of the A P Freeman XI playing West Indies at Gravesend in 1933•Getty Images

There were many games when Kent's team included both players and even days when the two would swap duties. He and Ames played against each other in Gentlemen v Players matches and the 1931 contest at Lord's saw Levett stumped by Ames off Hedley Verity for 6 before Ames was caught by Levett off Walter Robins for 2. The game was drawn but it is difficult to think the two men did not enjoy the occasion. "Hopper would roar with laughter when he made a catch," said Doug Wright. "You could hear it all round the ground. The Kent crowd chuckled along with him, sharing his delight."

RC Robertson-Glasgow even invited recollections of one of Dickens' most famous characters in his tribute to Levett's ability. "[He] is the most brilliant of English 'keepers for he brings off catches that would astonish you, and in routine work, if thus you can describe so exciting a craftsman, he is seldom at fault… He has the humour of Sam Weller and the vitality of a man who, by invincible conversation, eventually sells the unsaleable."

Kent were clearly dependent on Levett in the 1930s whereas Farrimond was an understudy at Old Trafford until Duckworth retired in 1937. The Kent keeper made only 45 appearances in second-team championship matches whereas his Lancashire counterpart clocked up 129 such games. And although Levett's career spanned four fewer seasons, he played 22 more first-class matches than Farrimond, 66 of whose 153 games took place in 1938 and 1939 when he was finally first-choice wicketkeeper.

Both men, of course, lost six seasons to the war. Yet having waited uncomplainingly to succeed Duckworth, whose appeals may have woken the dead, Farrimond found his career all but ended by the depredations of Adolf Hitler, another fellow much given to shrieking in public. While the proud Boltonian joined most of the world's population in resenting the Fuhrer's attentions, there is no evidence he bore his predecessor the slightest ill-will and it is this acceptance of his lot that makes his career particularly interesting.

As Keith Hayhurst points out in his affectionate tribute Farrimond was born, bred, married and buried in Westhoughton, which was, and is, a middle-class suburb of Bolton. Having made his debut in 1924 and found his path to Lancashire's first team blocked by Duckworth, who was two years his senior, he settled for his lot in life in a manner today's career-driven cricketers would find faintly astonishing. "He was technically proficient, undemonstrative and unpretentious in character," writes Hayhurst. "A patient and loyal man with a comfortable social life, he was content to receive less remuneration and play alongside his mates in the second team."

Bill Farrimond portrait•Getty Images

For all that he was chosen for two MCC tours and made his four Test appearances when injury prevented either Duckworth or Ames from keeping, Farrimond's ambitions never strayed far beyond Lancashire. Given that he played during two decades in which unemployment was a constant threat and in which home-ownership amounted to prosperity, such seemingly modest goals in life were not to be mocked.

Not everybody could be Herbert Sutcliffe and Farrimond never wanted to be. In his way he was exactly the type of player captured so memorably by Eric Midwinter in his assessment of the great Lancashire side of the 1920s.

"The professional cricketer was the genuine epitome of the respectable topside of the proletariat. Stable, watchful, complacent and a little self-satisfied, they knew their place and preferred it. They were tradesmen, skilled and decently paid. They would stroll, in their good boots, watch chains across their waistcoats, around the wintry streets of their spinning or weaving homelands, unpressurised by the stress of the mill hooter and admired by their peers. In the summer evenings they would sink their pints and smoke their pipes in the quiet second-grade hotels of Worcester or Canterbury, and then off again by train, to Taunton or to Gloucester."

Except that Farrimond was always glad to return to Westhoughton, where he owned a semi-detached house, if you please, and his neighbour was the Lancashire fast bowler Dick Pollard, another Westhoughton lad who also played four Tests. "They have only to step across the fence to compound a stratagem or celebrate a victory," observed Robertson-Glasgow. All of which might be faintly reminiscent of a Hovis advert and ripe for stylish Oxbridge satire until one remembers that Farrimond was probably one of the dozen best wicketkeepers in the world but was perfectly content to label himself as "Lancashire seconds and England." It is sometimes useful to remember that only in the past 20 years have professional cricketers flown in for two games here and three games there. The world has not always been small.

"It was 'Lancashire or nowt' with Farrimond," wrote Robertson-Glasgow. "They are not apt to wander in the North… He has the level and steady look which you see in old seamen who did much earnest 'gazing on the pilot stars'. His style, as you would expect, is calm. Perhaps he thought that his great predecessor had done all the shouting and falling over and demanding that Lancashire needed. He has a sort of noiseless brilliance."

Having risen to the rank of captain in the Second World War, Levett played only 14 more first-class games before retiring in 1947 at the age of 39. Farrimond was 42 when the war ended and he allowed himself just one more appearance for Lancashire. That was made in the 1945 Roses match, arranged to raise funds for Hedley Verity's family. Then he returned home and played in the Westhoughton team that won four successive Bolton League championships. . Just before he died he told Hayhurst that "he wouldn't have changed anything if given the chance. Being able to play the game he loved among his Lancashire friends was all he wished."

For more Odd Men In stories, click here

Paul Edwards is a freelance cricket writer. He has written for the Times, ESPNcricinfo, Wisden, Southport Visiter and other publications