Packer's circus

The circumstances were already in place. The Australian media magnate simply triggered the explosion

Gideon Haigh

21-Aug-2010

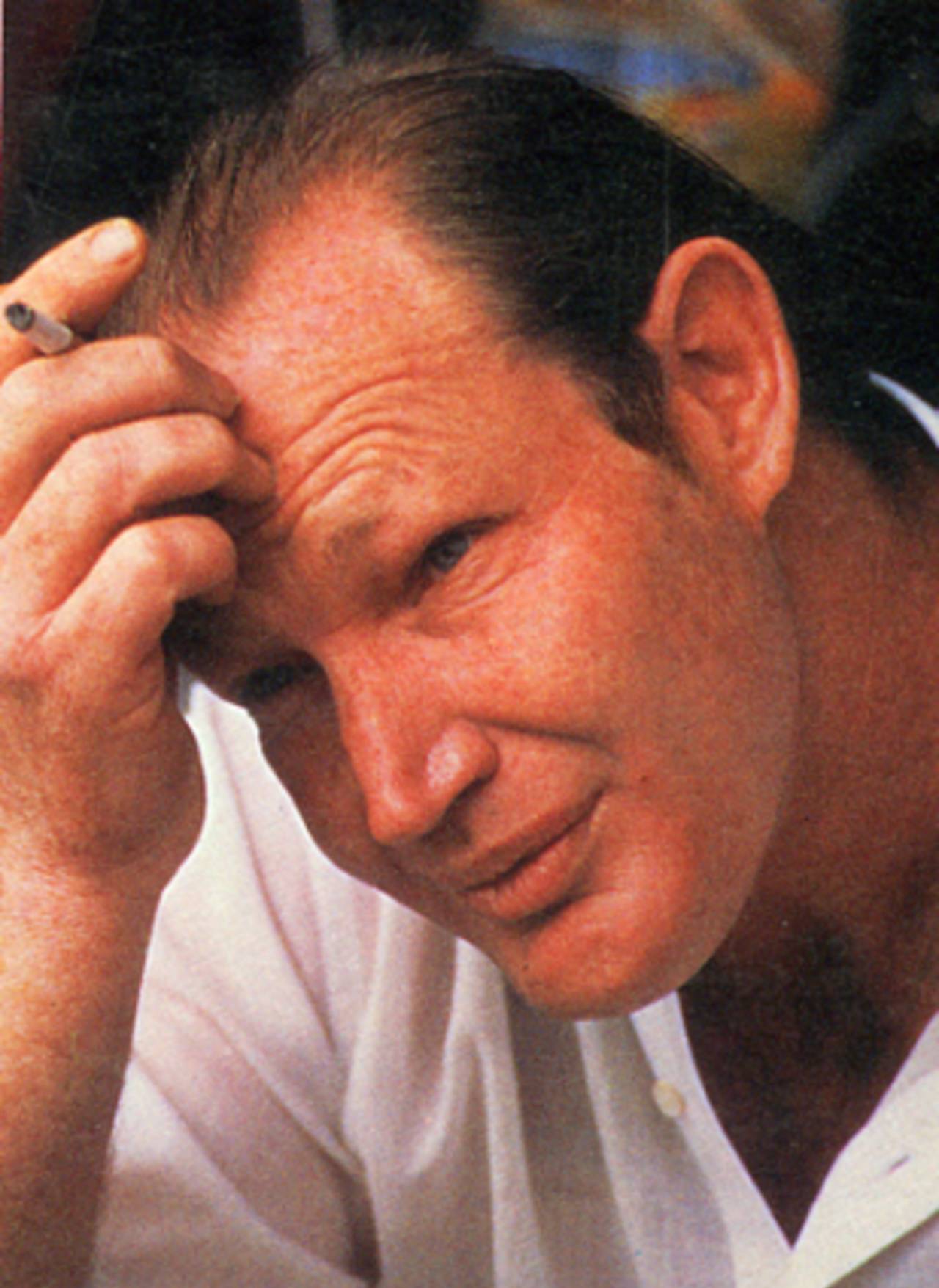

Kerry Packer: A knight without the title • The Cricketer International

1977

In his 1979 book, With A Straight Bat, World Series Cricket's chief administrator Andrew Caro looked forward to a Lord's banquet some 15 years later at which the toast was Caro's boss, "Sir" Kerry Packer. He imagined the Duke of Edinburgh gesturing to a portrait of the television mogul on the Long Room wall - between those depicting Sir Pelham Warner and WG Grace - and proclaiming that "without Sir Kerry, cricket would not have pulled its finger out".

The banquet never happened but it might still be justified. Cricket had gone decades in which it had altered less - considerably less - than in the two years of WSC, the professional cricket troupe Packer backed with his Nine Network in mind. Night cricket, coloured clothing, helmets and drop-in pitches were pioneered. Cricketers, paid like star sportsmen for the first time, became more aware of their worth in the marketplace. Administrators, wakened to the value that the media imputed to their sport, came to recognise television rights as an important revenue source. Mass marketing, embodied in the pop chant "C'mon Aussie C'mon", devised by admen at Mojo, took root in cricket and never went away.

The saga began in May 1977, when it was revealed that Packer had recruited the 35 best international cricketers money could buy for a series of matches to be screened by Channel Nine. The Australian Cricket Board had denied him exclusive broadcast rights for cricket and he had decided to roll his own.

The board fought a successful holding action in that first summer, 1977-78. The national team, rebuilt from young talent that Packer had not recruited, beat India 3-2; WSC, meanwhile, struggled to find an audience, despite its galaxy of talent, grandeur of design and gaudiness of promotion.

The summer of 1978-79, however, found roles reversed: while an inexperienced Test side was routed by England, WSC went from strength to strength. Packer's promotion was directed towards making WSC look more like official cricket rather than less, his Australian team more truly the representative of the people than its establishment equivalent; and the Chappells, Dennis Lillee and Rod Marsh were a persuasive unit. Establishment resistance crumbled: Packer got his exclusive rights and more.

In hindsight there is a historical inevitability about all the changes WSC wrought. They'd either already been dabbled in, or become factors in rival sports. What precipitated events was the availability of cricketers for a bargain price - it was learning how peeved Australian players were by their paltry wages that convinced John Cornell and Austin Robertson, WSC's architects, to take their proposal to a receptive Packer.

Even WSC's investment in the popularity of one-day cricket was hardly a blinding flash after 1975's World Cup. So the important aspect of WSC was not simply the changes but their speed: cricket had never changed so far so fast. It happened at a pace, in fact, that could never have been accommodated by cricket's existing institutional structures. We toast you, Mr P, even if Lord's won't.

Gideon Haigh is a cricket historian and writer. This article was first published in Wisden Asia Cricket magazine in 2003