Colin Milburn was about as far removed from the identikit picture of the perfect international cricketer as it was possible to be. So overweight that he could have starred in

Super Size Me - Morgan Spurlock's exposé of the fast-food industry. Dishevelled, disorganised and gradually drinking himself to death, it was astonishing even in the 1960s that England ever turned to him. These days, even at county level, he would not get a look in.

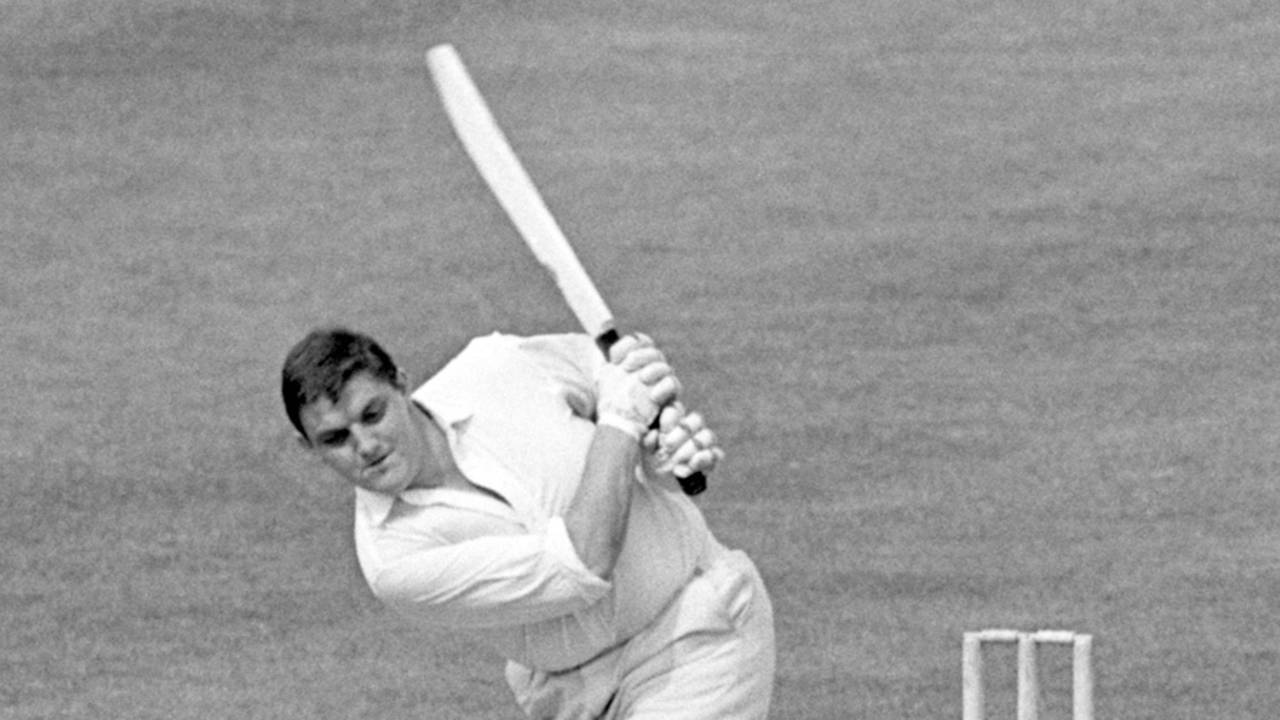

But that was much of Milburn's charm. For all his 18 stone ("and the rest" according to some of those who tried to change his ways at Northamptonshire), he was light on his feet, possessed of rapid reflexes and destructive of shot. The ball could disappear many a mile off a Milburn bat. Add his perpetual image of cheery bonhomie, his love for a joke and a night out, and he was an extraordinary antidote to the seriousness that pervaded English cricket half-a-century ago. For all the notion of the Swinging Sixties, in English cricket only the fat man was swinging.

An average of 46.71 in nine Tests tells of Milburn's talent. But the barbs were already out about his fitness when he lost an eye, and damaged the other, in a car crash in 1968. Northants had just beaten the West Indies tourists and Milburn was in celebratory mood. He lost control of the car, heading back to the Abington pub by the Northants ground for some more beers, and crashed through the windscreen. The Road Safety bill had been introduced in 1966, the breathalyser a year later; seat belts became compulsory in 1983. It was a tragedy of its time, not carrying the mantle of shame that it would today.

Milburn's gloriously unlikely career, and the extent of the mental-health issues that welled up after his accident, are explored in

When The Eye Has Gone, a one-man play written by Dougie Blaxland (aka

James Graham-Brown, the former Kent cricketer), which is about halfway through its tour of the county grounds. It has been produced in association with the Professional Cricketers' Association to promote mental health and well-being. In a desperately unhappy turn of fate, Alan Hodgson, Milburn's former county team-mate, flatmate for a decade, and a primary source for much of the material, died a few days before the premiere.

The strong implication is that Milburn's seeds of self-destruction were sown even before his car accident, and the fact that this is a one-man performance adds to his sense of isolation. "The more you are hurt, the more you smile," was actually the cricketing advice of his father, Jack Milburn, a Durham local-league slugger, about how to take a blow from a fast bowler, but it neatly widens out into Milburn's message for life as he learns from childhood to tell a succession of fat jokes against himself.

Only cricket sustains him. A long-standing engagement eventually falters because he prefers to be out with the lads. He cannot hold down a job in the off season. Whenever he seems down, his mates do what men did - still do - and take him to the pub to cheer him up.

Milburn's accident hastened a decline that perhaps was inevitable, although his mother, Bertha, felt that effectively his life was ended on that night. With his left eye lost - his leading eye, unlike in the case of the Nawab of Pataudi, whose example Milburn hoped he could emulate - and his right eye badly scarred, his prospects of a comeback were minimal, but his bedside manner was so defiant the hospital report that year suggested that it was he who was lifting the nurses.

Ill-advisedly, Northants allowed him one last heave in 1974 - their version, perhaps, of caring for his welfare - and predictably he did not succeed, save for an hour at Guildford against Surrey in light so bright that "the sun lit up the sky like a meteor", one of the most moving passages of the play. But then the clouds rolled in and they never departed.

"I tell them every fat joke I know… I am 'Comedy Ollie', the joker, but it never occurs to you that one day you might run out of jokes."

The play is set in the bar of the North Briton pub in Newton Aycliffe on the last night of his life. It is one last performance for "Comedy Ollie", a traipse through the highs and lows, the tales, the songs and the bonhomie that characterised his life. Feedback from those former Northants team-mates who have seen it has been highly positive: it connects with the Ollie they knew well. Even now, there is a reluctance to accept that there was too much unhappiness, and to some degree the play respects this. Nevertheless, as Milburn reminisces, there is little sense in Dan Gaisford's performance of the alcoholic exhaustion that had set in. His moment of death is delicately skipped around: not so much as a sound effect.

Inevitably this is theatre at its most rudimentary. There is no set, apart from a table, chair and a large glass of gin and coke. Milburn's girth is symbolised by a bit of extra padding around Gaisford's middle, and he is not an overweight man. But by no stretch of the imagination is this austere theatre: there is much laughter to be had. I don't know if the baby balloon joke was Milburn's, but it should have been.

When I was eight, I would pretend to be Ollie Milburn in a knockaround cricket match on a patch of village green. Overweight at the time as I was, it doubtless had its psychological benefits. The role duly chosen, the intent was to try to hit the ball many a mile, a feat occasionally achieved alongside the tumble of many wickets. "Can you be Boycott instead," my mate Bob pleaded one day. "We've only got one tennis ball left."

Late in his life, in the mid-1980s, I joined Milburn as an emergency fill-in for an hour's county cricket commentary at Scarborough on a premium telephone service. He was hungover, shambolic and had little to say. This being Scarborough, I was probably hungover too, and had even less to offer. People were expected to phone in and pay about 30p a minute. There was surely nobody on the line. It was probably his last job and it paid his bar bill. His decline was all too apparent.

When The Eye Has Gone succeeds in capturing Milburn's uniqueness - not an overused word in this case - conveying something of his life at his highest and lowest moments. It left me hankering for something even more ambitious; in its exploration of the sadness behind the famous sporting figure there were reminders of The Damned United. Being about football and Brian Clough, that had a successful theatre run. Cricket, by contrast, must take what it can get but all involved in this production, the PCA included, have delivered not only an entertaining night's theatre but a story that needed to be told.

When The Eye Has Gone is part of the PCA's commitment to mental-health and well-being issues, notably the Mind Matters series, which warns about addictive behaviour through alcohol, substances or gambling and educates about the warning signs of anxiety and depression. David Hopps is a general editor at ESPNcricinfo @davidkhopps