Greg Chappell and the Long Run

We all want to know why we lost to Bangladesh and then Sri Lanka

Mukul Kesavan

Feb 25, 2013, 10:25 PM

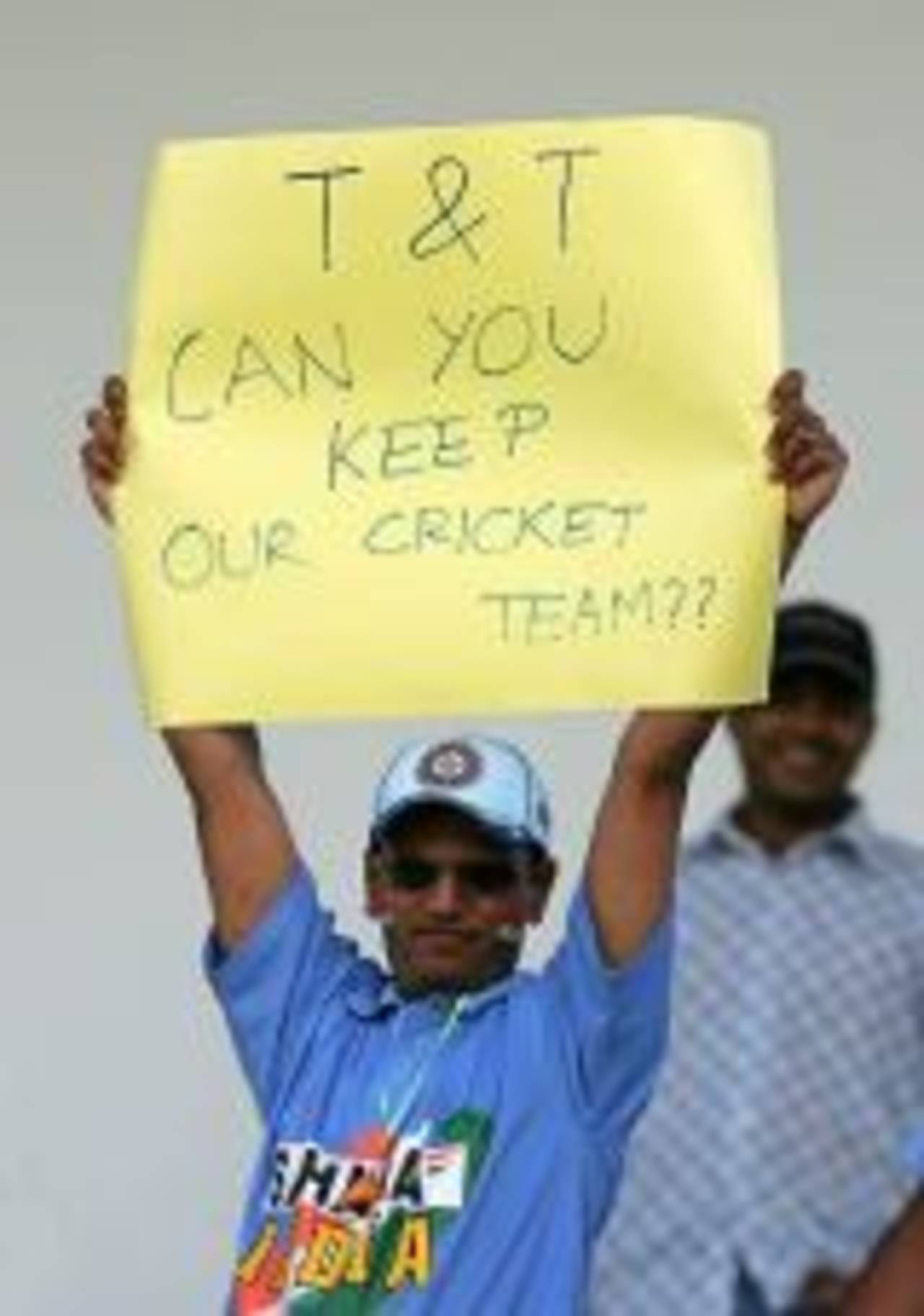

AFP

For historians, the controversy around India's exit from the world cup has a familiar rhythm and pattern. On the face of it all the stakeholders in Indian cricket—the fans, the BCCI, the coach, the captain—want to get to the bottom of this unexpected failure. We all want to know why we lost to Bangladesh and then Sri Lanka. We want the causes for our defeat laid out: we want, in short, a historical explanation for this catastrophe. Post-mortems shall be performed on the Great Slip of 2007, months, years after the World Cup is done. In just this way do historians of the rebellion of 1857 still debate the reasons for that bloody episode.

No one will ever agree on why we got eliminated because every interested party will set his causal explanation in a different time frame. Greg Chappell has already indicated that he favours a long term explanation for India's poor performance. In a press conference after India's loss to Sri Lanka, Chappell was understandably defensive. Quizzed about the reasons for India's losses, he repeatedly said that "we didn't play well enough." When asked why India didn't play well enough he had this to say:

"Well I don't think India has won a tournament overseas since 1985. There is a bit of history to it. There are obviously some reasons."

It seems churlish to point out that the questioner hadn't asked why India hadn't won the World Cup, though this is the question Chappell chose to answer. He was merely asking why we had been slung out in such short order and given the fact that we had reached the finals just four years ago, it was a reasonable question. Be that as it may, Chappell and his admirers were setting out a preliminary sketch of their history of our decline.

It goes like this. The base of Indian cricket is the first-class game. The Australian school (to which Chappell and Dravid belong) argues that there are too many first class teams. These make the Ranji Trophy unwieldy and the huge difference in the level of cricket played by, say, Mumbai and Jharkhand, makes the first class game uncompetitive. Indian cricket at the very top can only improve when this system is reformed and a premier league created that will feature a maximum of six or seven teams following the Australian model. In addition Indian cricket needs paid selectors unconnected with the politics of zonal cricket, professional managers, and curators who can produce the pitches that India encounters overseas.

Once this reformed structure is in place, the skills of top-tier players have to be professionally honed by putting a process in place. Process became something of a totemic word for Chappell and Dravid. It was generally invoked to defend changes in the batting order and team selection and its purpose was to indicate that the choices made were not random but determined by a process that would, in the fullness of time produce a strong and versatile team. Which brings us to another part of Chappell's press conference.

Q. Another word that has been mentioned a lot is 'process'. What went wrong with the process?

A. That's an inflammatory question and I'm not prepared to answer it.

Even allowing for a natural defensiveness, 'inflammatory' is a curious description of the question. It's a pointed question, even a sarcastic one, given the mantra-like significance of 'process' in the team management's jargon, but inflammatory? Chappell's thin-skinned reaction to the question is probably explained by his feeling that the assembled journalists were trying to get him to take responsibility for the debacle when he clearly thought the responsibility ought to be shared around. Feeling as he did, that the Indian press was trying to assign blame (rather than analyse the causes of failure) Chappell took refuge in the longue durée.

The problem is that structural explanations don't really explain success or failure at the highest level in team sport. Brazil has won the soccer world cup four times. England, with one of the richest and best organized football leagues in the world has won it once. The Dutch, who systematically implemented a 'process' called 'total' football for years never won it at all.

The real difference between the Australian team and the Indian team in structural terms is that the former is thrown up by a population which routinely plays outdoor sport into adult life while the latter is chosen from a population where a statistically insignificant number of people do. The despairing references to a nation of a billion people failing at every sport are beside the point.

So are ambitious plans to restructure first class cricket. I don't think anyone has plausibly demonstrated that the infirmities of the present system have led to the wrong players being systematically chosen for India's Test or ODI teams. There has always been debate about the selection of Indian teams and dark aspersions cast on the corruption of the selection process, but I don't see any Tendulkars or Kapil Devs blushing unseen in some cricketing desert. If anything the number of players to make the Indian team from obscure provincial sides has risen steeply in recent times. Think of Mahendra Singh Dhoni, Irfan Pathan, Munaf Patel, Mohammad Kaif and Suresh Raina and it becomes apparent that as far as throwing up talent is concerned, the system's working.

In any case, it's the same system that got us to the final in 2003, so perhaps we should look for explanations in the shorter term and focus on policies and personalities, rather than structure. It's a form of history writing that used to be unfashionable but is making something of a comeback.

I think we lost because Chappell, with the best possible intentions, tried to shake the team out of its settled routines by recruiting new players and rotating their roles. He bet on youth and fitness, on developing the all round skills of players like Dhoni and Pathan, and on undermining notions of seniority and hierarchy. He made an example of Ganguly to this end, made his indifference to slow-moving specialists like Laxman obvious and built up players like Raina on the strength of their fielding skills.

All of these policies are theoretically defensible: the problem is, they didn't work. Raina wasn't ready for prime time as a batsman, Pathan's bowling fell away, the experiments at the top of the order failed and by the time the World Cup came round, the Indian team looked remarkably like the one John Wright had handed over. Ganguly was back and he rejoined a team that had been stirred and shaken so hard that it was an anxious bunch of individuals with no esprit de corps. It didn't help that its captain was so tense and care-worn that his batting form declined.

If the atomization of the team was the medium term cause, the short term trigger was daft team selection. It still isn't clear what Uthappa was doing in the team or what Laxman was doing out of it. Or why the job of bailing India out in the crunch game against Sri Lanka was handed to a rookie instead of being given to Tendulkar who has scored nearly all his one-day centuries opening the batting.

It's in choices like these that the causes of India's embarrassing exit from the World Cup should be sought. A seven team Ranji tournament, the art of total cricket and paid selectors may well be useful in the long run, but it's unwise to base a coaching process on that projection. In the long run we're all dead.

This piece first appeared in the Telegraph.

Mukul Kesavan is a writer based in New Delhi