Is England falling out of love with cricket?

Much of the game still runs to the timescales of a different, distant age. Nothing about the way we live now suggests these ideas still work

Jon Hotten

May 12, 2015, 12:43 PM

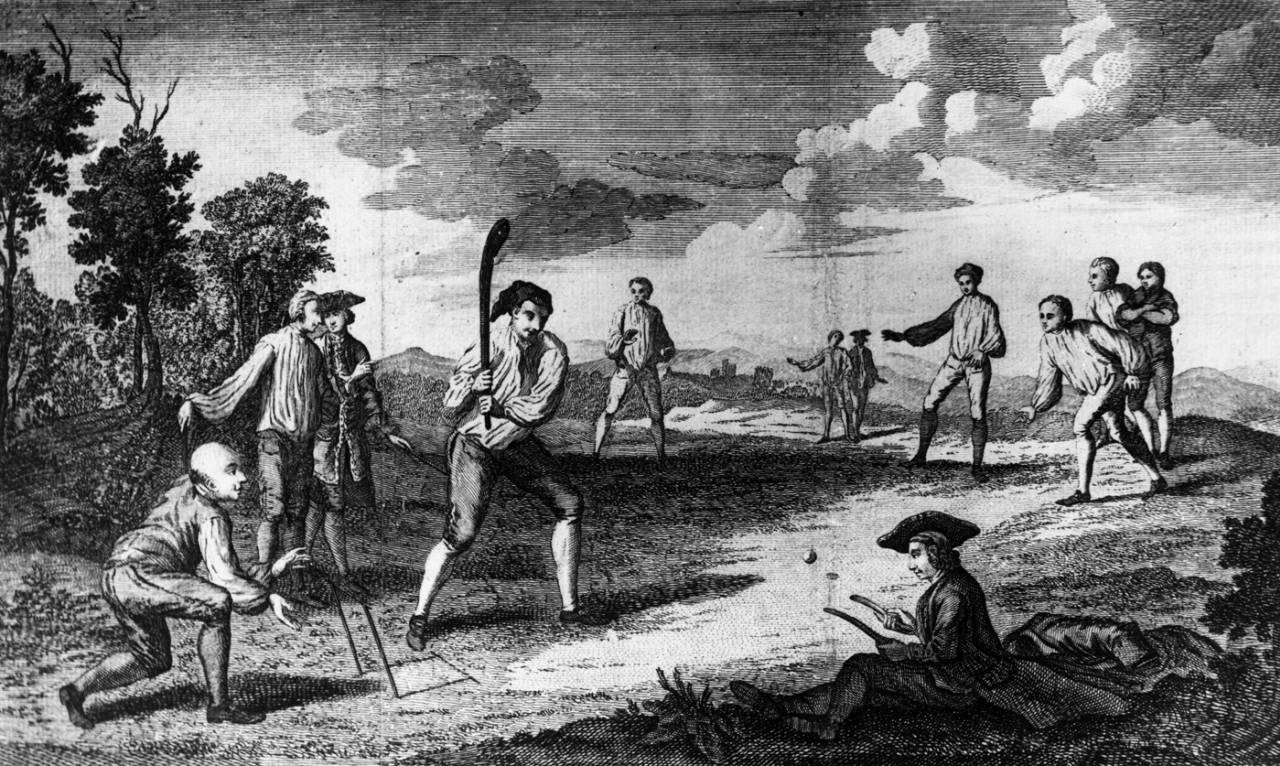

Before the United States of America, there was cricket • Getty Images

On December 14, 1873, the P&O liner Mirzapore docked in Melbourne. Standing by the rail were WG Grace, his new wife Agnes, and a team of English cricketers. "The champion himself looks splendidly, and is a fine, strapping, muscular young Englishman…" reported the Melbourne Age the next day, going on to describe how the thronging crowd offered three cheers to Grace as he took his first steps on Australian soil.

They may not have known exactly what he looked like, but WG Grace was already famous in Australia. He was also the best-known sportsman in Victorian England, a proto-celebrity whose epic life and career would pull cricket from its scattered origins into its recognisable, modern form.

He had grown the great black beard that would create an image that has endured until today. Grace quickly came to represent not just English cricket but a certain kind of Englishness itself. When Monty Python needed a visage for the face of God in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, they chose Grace.

From the moment he began redefining the parameters of the game, WG's mighty image has become unshiftably associated with what English cricket is.

****

On September 12, 2005, England's exultant, exhausted cricketers walked back into the home dressing room at The Oval having achieved the draw that won the Ashes back for the first time in 18 years. Phil Neale, an ECB manager, put his head around the door and said: "Right lads, quick chat - you've got an open-top bus tour tomorrow morning, 9.30… The Lord Mayor's Palace, Ten Downing Street, Trafalgar Square and Lord's…"

England's coach Duncan Fletcher and captain Michael Vaughan had kept the news quiet as they hadn't wanted the Australians getting wind of the plan - the greatest team on earth were already doing everything in their power to wreck English dreams at the death.

People jamming pavements, hanging out of office windows. Prime Minister Tony Blair at the door of No. 10 to greet the team. The day (after the last 2005 Ashes Test) was a celebration of the transformative power of Test cricket

All that the players wanted to do was celebrate the win, revel in the lifting of the intense pressure of five matches in 54 days. They had taken part in that remarkable game at Edgbaston, the second-closest win in history, and then Old Trafford, with 10,000 people locked out of the ground by 8am on the final day, but Fletcher had banned them from reading the papers. They could only guess at the impact the series was having, and they wondered whether anyone would show up for the parade.

By 9.30 the next morning, as they fought terrifying hangovers in the smiting early morning sunshine, the streets of London were lined with people. They were jamming pavements, hanging out of office windows, filling Trafalgar Square with a cheering, happy mass of humanity. Prime Minister Tony Blair, a consummate judge of public mood, made sure he was at the door of No. 10 to greet the team. The day was one long, hazy, booze-sodden celebration not just of victory - although that was ambrosia-sweet - but of the transformative power of Test cricket.

****

When I feel like a little cricketing psycho-geography, I don't have to travel far. Three miles from home is Hartley Wintney, where the village green cricket ground, flanked on one side by a pub, on another by some towering oaks and a third by picture-book tumbledown cottages, has been standing since 1770, making it perhaps the oldest cricket ground in England to have continuously been played on. David Harris, the feared underarm bowler of the 1790s, was born a mile or so away in Elvetham and learned his cricket there. Even in winter, when dogs gallop across the frosty outfield, it's possible to stand there and feel the game deep in the earth.

Five miles in the other direction is Farnham's hilltop ground, set next to a castle above the town. Farnham's first game was played on August 13, 1782, at their early home at Holt Pound, a patch of ground still visible behind the local pub. It was known as "the Oval", from where the London ground took its name. That first match, against Odiham, appears from the scorecard to have featured the 16-year-old "Silver" Billy Beldham, who would become the greatest batsman of the underarm age.

Cricket's first celebrity: the fearsome, magnificently bearded WG Grace. Would he recognise life as we live it these days?•Print Collector/Getty Images

In 1784, Silver Billy faced David Harris when Farnham played Hambledon - Silver Billy claimed in his "Reminiscences" of 1836 that he made 43 and was watched by the Earl of Winchilsea, who became his patron.

If you want to feel how far back in time these places and people go, then think about this: 1770 is closer to the reign of Elizabeth I than it is to that of the current Queen. In 1782, the American War of Independence still had a year to run. Samuel Johnson died in 1784, the same year the first mail coach ran between Bristol and London. The outlaw Jesse James was robbing stagecoaches even as Grace docked in Australia.

Life in 2015 would be unimaginable for David Harris or Silver Billy, and maybe even for Grace, who would have seen its first intimations in the arrival of the telephone and the motor car. And yet we expect the game to cross this great range of experience and remain intact, and at its core, unchanging: 22 yards, three stumps, two bails, two teams, bowler, batsmen, fielders, umpires.

****

How realistic is it for cricket to prosper in our atomised, disposable culture? Much of it is an anachronism, still running to the timescales in which it was invented. County cricket on a weekday? Test matches that take five days to play? A hobby that eats up the entire weekend? Nothing about the way we live now suggests these ideas still work.

The game has made its concessions of course. The first professional limited-overs game came in 1964; the first ODI in 1971. T20 arrived in 2003. These formats suggested a realisation that cricket - or anything - has to accelerate to match the environment in which it exists.

We are realising that we live in a "time-poor" age. But cricket demands our time, as spectators and as players. ECB figures say the number of cricketers between the ages of 14 and 65 have dropped from 908,000 in 2013 to 844,000 last year. Five per cent of formally organised matches were conceded because one side or other failed to raise a team. Cricket demands our money, too. Ticket prices for internationals vary throughout the country but routinely top £100 for a seat. The 2005 Ashes series was the last to be shown live on terrestrial television. All domestic and international cricket, plus franchise tournaments the IPL and the Big Bash League, now require a subscription of around £20 per month to watch.

County cricket on a weekday? A hobby that eats up the entire weekend? Nothing about the way we live suggests these ideas still work

If, in our time-poor, cash-strapped, recession-hit country, cricket is trying to make itself difficult to access and harder to love, it probably couldn't do a better job. Even the Ashes, rejuvenated by 2005's indelible marvels, are being over-supplied. This summer's series is the third since 2013. England play 17 Test matches in a calendar year. Who, apart from the media, has time or money to watch all of that?

The past is a foreign country, as the old line goes, but then England is a foreign country too. Rarely has its hemispherical disconnection from the rest of cricket seemed as relevant. Somewhere between 1979, when England reached their first ODI World Cup final, and 1992, when they reached their last, the game became something different. Those losses did not haunt the country in the way that a World Cup final loss in football might. And had England won, they would not have ignited something in the way that 1983 did for India or 1996 for Sri Lanka.

These were cultural eruptions that allowed countries to see themselves in a new way, through a new game. England has never had that, and became even more entrenched in the connection to Test cricket, and by extension its connection to the past.

Only England could invent T20 cricket and then immediately fail to hold on to either its significance or its structure. It's a World Cup that England have won, yet it's often tucked away at the end of a list of achievements for the side that took three Ashes series in the years surrounding it. For whatever reason, it just means less here.

The franchise system has reignited domestic cricket in India and Australia but terrifies the 18 counties, and perhaps its inception here would do something irrevocable to the county system. Another tie to the past would be gone then.

The Ashes has provided England with its most magical cricketing moments of late, but there is a surfeit of the rivalry now•Getty Images

The County Championship is perhaps the ultimate anachronism, serious cricket played out to an unwatching world, yet its oddness makes it even more loved and clung-to by people who will never go to a game. Instead it has a new half-life as men and women in offices and call centres and a hundred other places of work follow it on their tablets and laptops and phones via a series of live blogs that have flourished in its gentle, winsome atmosphere. The technology is new but this love is about the past, and about the lives we can no longer have.

****

At the start of last season I interviewed Alastair Cook for All Out Cricket magazine. We met at The Oval, where he was going to play for Essex against Surrey in the County Championship. The 5-0 Ashes defeat was still a red-raw wound. Kevin Pietersen had been sacked by the ECB's new managing director Paul Downton, who had publicly backed Cook as captain. Andy Flower had moved to Loughborough. Cook had called Graham Gooch personally to tell him of his removal as batting coach. Downton had appointed Peter Moores and called him "the outstanding coach of his generation".

It had been designed as a decisive response to a winter of despair, and the ECB was selling it hard, but it, and Cook, had not caught the public mood. It was an uneasy morning. Cook was guarded and defensive. He'd talked before about his "vision" for the England team, but he found it hard to define beyond saying, "I think there's a way that you conduct yourself as an England player. And the way you play your cricket."

He also said he felt the team had been "quite insular" and needed to become "more accessible" to the fans and the media. It was a striking statement, in part because it was clear how hard he found it to open up during his own media appearances. The disconnect caused by the famous "England bubble" was apparent even to England's captain (perhaps especially to England's captain), and yet with all of the weight of pressure on him, he seemed unsure how to go about reducing it.

We spoke again on the phone a few days later, by which point England had fostered some goodwill by playing Scotland in an ODI, getting the game on even though the weather was terrible. Cook had spent much of his time in the field standing in a puddle at mid-off. He went out of his way to make the call and he was far more engaging. At the very least it seemed as though the will to reconnect was there, from the players if not the wider establishment.

For every step forward made by the players in "reconnecting" with the wider public, it seemed as though the ECB took them two steps back

The summer veered back and forth from good to bad and back again. For a while Cook couldn't score a run, and then in Southampton against India he batted through the first morning and walked off to a standing ovation that was moving to see. He missed out on a century but when Moeen Ali bowled England to the win, the players spent a long time orbiting the boundary signing autographs, and it appeared the gap between them and the fans was growing smaller.

The Pietersen decision reverberated, though, and the news that he would publish a book at the end of the season hung over England. For every step forward made by the players in "reconnecting" with the wider public, it seemed as though the ECB took them two steps back. Cook was sacked on the eve of the World Cup, a tournament that, as far as England were concerned, seemed to have been staged purely to point out how far adrift of the rest of the world they were.

****

Pietersen's book came out. Two employees of the ECB had to go to a launch event in Manchester to get an advance copy and find out what was in it. Pietersen went out on a promotional tour that would have been the envy of a Booker prize winner. His London appearance was at the Institute of Education, not far from Euston station. Admission was by ticket only, and the price also included a copy of the book.

Huge piles of them sat at a desk in the venue reception. Inside the auditorium, there must have been five- or six hundred people. The atmosphere was charged. Pietersen spoke for more than 90 minutes. What was noticeable was that all of the questions from the crowd were about cricket rather than what had happened in Australia, and when he talked about his batting and how it made him feel, he was a fascinating mix of assertiveness and vulnerability. He was funny too, and surprisingly geeky. It was hard to think of any other cricketer in England who could have done something like it, gaining traction on the news agenda with a book, people filling auditoriums to hear him speak.

The book itself was awful. It was repetitive and lacked the engaging voice Pietersen had shown at the launch. Yet its key points continued to rumble like distant thunder over England: an oppressive, bullying team culture; a squad pushed beyond its physical and mental limits by the schedule imposed on it; a reliance on statistical probability rather than natural flair; a reductive, obsessive coaching system that eliminated the kind of risk-taking individualism that Pietersen personified.

Kevin Pietersen's book was an awful read, but its key points rocked English cricket•Getty Images

In the olden days that I recall from my start in journalism, the way to make a long-running narrative die was to bury it slowly, let it wither on the vine as attention inevitably turned elsewhere. Social media no longer allows such a narrow dictation of the agenda, and Pietersen grasped far better than the ECB that unmoderated, unmediated platforms - through which he has a reach of millions - kept everything about the story fresh on an hourly basis.

When Colin Graves became the ECB's chairman elect and Tom Harrison its new chief executive, one of the first moves was to engineer an opportunity to defuse the Pietersen situation by opening the door to his re-selection. It was a smart decision, easing power away from the unloved Downton and placing responsibility back on Pietersen and the rest of England's players to perform on the pitch and behave in the media. Downton's job was dead in the water from that moment. A restructure brought Andrew Strauss as Director of Cricket and the internecine nature of the argument took another turn. Pietersen was no longer sacked, but could not be selected either. It's what generations of Civil Service Mandarins would recognise as a classic English compromise.

****

Other Graves and Harrison ideas, such as a franchise T20 competition and a suggestion of four-day Test cricket, at least speak of a flexible agenda and a recognition that it is no longer 1873, or even 2005.

As a nation England is especially susceptible to nostalgia. We hanker for times and places that never really existed. Nostalgia ties us to the past and holds us there. Until we let go of it, a part of our cricket will always exist there too.

But are we out of love with the game? Is it possible to quantify such a thing?

In 2003, England won the rugby union World Cup with a last minute-drop goal from Jonny Wilkinson. The nation stood still, and for a while there was talk of rugby taking this huge step forwards. But then it didn't. Instead it slipped back to where it had been. After 2005, cricket took over. Then cricket slipped back. This year, the Six Nations rugby union championship staged a made-for-TV finish, with the three final games played consecutively over a single afternoon. It engineered a ferocious, gripping climax. Almost nine million people watched it on the free-to-air BBC.

The people who sell sport want certainty of attendances and ratings, and yet sport only works when there is uncertainty of outcome. Cricket may be caught forever in this cleft

How many of them will stay? It's impossible to say. But perhaps this boom and bust is as natural to the uncommitted watching public as the ebb and flow of success and failure is to professional sportsmen. The people who sell sport want certainty of attendances and ratings, and yet sport itself only works when there is uncertainty of outcome. Cricket may be caught forever in this cleft. Ironically, other sports that demand commitments of time and money to play, golf and tennis for example, look green-eyed at the T20 format. Anything that can compact a long game without reducing the adrenaline-buzz (and the money) looks like the future to them.

****

This story is supposed to be about the soul of cricket, because unless there is soul, people won't continue to love it. The game's fathomless psychological depths will always have an appeal. Aside from those ECB participation figures, I can offer only anecdotal evidence of its health, but I have played hundreds of matches against thousands of people since I was 11 years old, and apart from the natural passing of time, it feels the same as it ever did. Amateur captains are still filling teams at the last minute (one of my team-mates, who skippers his own occasional side, is not averse to approaching strangers in supermarkets a few hours before the game if he's desperate enough, and sometimes it works too) but even on lazy Sundays we face many a hard-hitting young batter and hot-headed opening bowler.

They attack the game madly. The single biggest change I have seen since I started playing is in how hard the ball is hit. Young guys just want to smack it, far and often.

I remember once, many years ago, being on the ground for a double-hundred, but it was made with a 30-yard boundary on one side. I can think of three scores of 150 I've seen in the last couple of seasons. It's a step-change that echoes the pro arena. What they see there, they want to experience. I grew up watching Geoffrey Boycott. They have grown up with Chris Gayle.

The game renews, as it always has. If it can survive across the oceans of time that separate us from the discovery of Australia, the French and American Revolutions, the First and Second World Wars and the ministrations of ECB president Giles Clarke, we should perhaps at least have faith in our abiding love for it.

Jon Hotten blogs here. @theoldbatsman