The changing face of a very English game

An American's view of the Stanford Super Series and Twenty20's growing influence

Andrew Miller

Oct 31, 2008, 3:51 PM

| ||

Something strange has happened to the staid old game of cricket. As the cliché goes, this is the sport that you can play for five days straight and still not get a result at the end of it all - a quirky state of affairs that delights those who understand the intricacies involved, but baffles anyone on the outside looking in.

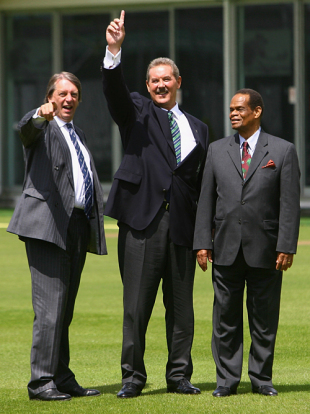

In the past 12 months, however, that most quintessential of English pastimes has undergone a make-over for the 21st Century, and would you believe it, there is an American right at the heart of the revolution. Sir Allen Stanford is a Texan billionaire with cash to burn. He made his fortune in real estate during the property boom of the early 1980s, but is now a citizen of the tiny Caribbean island of Antigua, from where he is making his bid to change the game forever.

Stanford's premise is simple. On November 1, the 27th anniversary of Antigua's independence, he is hosting a one-off fixture at his purpose-built ground, between England and the Stanford Superstars - or West Indies, as they might as well be known. And there is no question of this one ending as a draw. A prize pool of US$20million is up for grabs, of which the eleven players on the winning side will pocket a cool US$1 million each. As for the losers, they will go home with nothing.

It is the biggest single purse in the history of professional team sport, and it has been made possible by the exponential growth of the newest and most talked-about format in cricket. Twenty20 cricket is a scaled-down, sped-up version of the game that has lobotomised the old mystique and made it accessible to audiences that might once have yawned at the prospect. A 30-hour contest has been squashed down to three, and accessorised with coloured clothing, jet-black bats, floodlights and music. This is not cricket as the traditionalists know it, but with the stakes this high, it undoubtedly counts as entertainment.

The motives for Stanford's involvement in cricket are not entirely clear - some say fun, others say business, but it is probably a combination of the two. By his own admission, he is no philanthropist, but by that same token, he recognises the huge business opportunities that reside in sport. In particular, he recognises that, for a game that professes to be global in its outlook, there are some remarkable gaps in cricket's market. The USA, for instance, has never given the sport a second glance, but Stanford's outrageous offer has at least caused a few unconverted heads to be turned in his direction.

It is also possible that there is a human element buried somewhere deep beneath the brashness. When Stanford moved to the Caribbean shortly after Antigua's independence, West Indies' cricketers were the undisputed champions of the world - a toweringly aggressive unit whose fast-bowling resources were the envy, and the fear, of all opponents. Since the turn of the millennium, however, their fortunes had dwindled almost to vanishing point - betrayed by complacent administrators and undermined by economic realities. For the athletes among the Caribbean's youth, fame and fortune was to be found in other sports: football, basketball, track and field, to name but a few.

Sensing this discrepancy, in 2006, Stanford reinvigorated interest among the islands with a hugely successful domestic tournament. Guyana, the inaugural champions, made off with a cheque for US$1million, a bounty worth 200 times as much in their native currency. He is not the first entrepreneur to take hold of this format and run with it, however. In April 2008, India - cricket's financial powerhouse - redefined the game's possibilities when it unveiled the Indian Premier League, a franchise-based tournament that melded the worlds of sport, fashion and celebrity into a month-long fiesta that left the players and public gasping for more when it was over.

Stanford, however, was not a fan, and accused the Indian board of behaving like a "900lb gorilla" for the haste with which they had ushered their new concept onto centre stage. Mind you, his response - to slam $20 million onto the table and declare "take it or leave it" - seems every bit as apeish, but the fact that England and West Indies were so eager to accept his challenge gives an insight into the boardroom battles that cricket's new-found cash-cow is causing. Many of England's star players were eager to join the IPL party but were not released from their contracts because the timing clashed with the English season. This match was intended as a very high-profile sweetener. It remains to be seen whether the cream will turn sour.

Andrew Miller is UK editor of Cricinfo