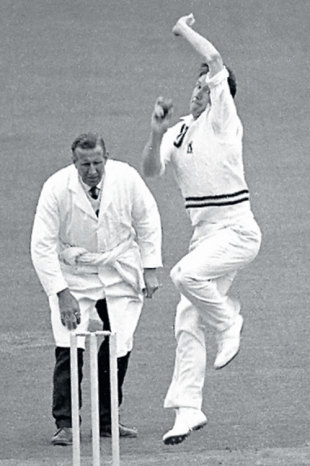

Tom Cartwright

Wisden's obituary for Tom Cartwright

15-Apr-2008

| ||

Cartwright, Thomas William, MBE, died on April 30, 2007, aged 71.

Tom Cartwright was a cricketer's cricketer. Perhaps no player of his generation

had so much respect from his colleagues - for his abilities, his character, which

was forceful without being abrasive, and his love and knowledge of the game.

Not everyone was so appreciative: committee men often thought him truculent,

and he played only five Tests for England, a figure that does no justice to his

skills or his standing.

Cartwright grew up in Coventry, and the family were forced out of their home

for a month by wartime bombing. He himself started work in the Rootes car

factory, but Warwickshire had spotted his batting, and in 1952 he accepted a pay

cut to join the then county champions. He made his first-team debut, at Trent

Bridge, when he was just 39 days past his 17th birthday, and made an unflustered

82 - no one younger had scored a Championship fifty since 1906. There was no

instant stardom: immediately afterwards, he returned to his Rootes. The next season

was harder when he was promoted to open and could not quite sustain the position.

National Service followed, and it was 1958 before Cartwright finally made a

century, 128 against Kent, and secured his first-team place. He was bowling his inswingers more now, and at Dudley the following summer came what he regarded

as the pivotal moment of his career: "I just ran up and the ball swung away," he

told his biographer Stephen Chalke. "It was the first time I'd done that since I

left school. The miracle was that I knew exactly what I'd done."

In 1959 Cartwright scored 1,282 runs and took 80 wickets, was chosen for the

Players, long-listed for the Caribbean tour, and talked about as Trevor Bailey's

successor; Warwickshire leapt up the table. After an injury-hit year in 1960, he

returned to form with both bat and ball, and in 1962 became the first Warwickshire

player to do the double since 1914. After a near-miss in 1963, he finally made

his Test debut in the Old Trafford Ashes Test of 1964 when both teams passed

600. But Cartwright ("England's best bowler" - Wisden) stoically got through 77

overs and enhanced his reputation, and attracted approving murmurs again in the

rain-ruined draw at The Oval. He was picked for that winter's South African tour,

but struggled with both injury and his distaste for apartheid - he was, then and

always, left-wing in his politics. The following summer, Cartwright played twice

more, taking six for 94 on the opening day at Trent Bridge when everything was

overshadowed by Graeme Pollock's batting. Before the close, he broke his thumb

attempting a return catch: though he kept going and took two more wickets, he

would never play another Test match. His batting fell away in time but his bowling,

on uncovered county pitches, remained awesome, and he averaged less than 20

for eight of the next ten seasons. He had a rare mixture of unrelenting accuracy,

cunning and skill, which included the ability to bowl an inswinger from close to

the stumps and an outswinger from the wings. Perhaps no one ever thought more

about the art and craft of bowling.

All this was recognised in 1968 when Cartwright was picked again, this time

- astonishingly - in the touring party for South Africa from which Basil D'Oliveira

was omitted. There was a huge furore, and Cartwright was battling a shoulder

injury, a reluctance to be away from his young family and his ambivalence about the morality of touring South Africa at all. Originally, he told Chalke, he believed

the tour should go ahead, but then he saw a news item saying the whole white

parliament in Cape Town had stood and cheered when the exclusion of the nonwhite

D'Oliveira was announced. "When I read that, I went cold," he said. It for

ever remained unclear, perhaps even in Tom's mind, which reason was uppermost

for his withdrawal - though the injury was the one cited publicly. The rest really

is history: D'Oliveira replaced him, South Africa cancelled the tour, and England

would not play another Test against them until 1994.

Cartwright came back as strongly as ever for Warwickshire in 1969 and, amidst

some messy committee-room manoeuvring, had the chance to become the county's

captain and/or coach. But he was attracted by an offer to coach at Millfield and

play for Somerset, and defied precedent by fighting off an attempt by his former

employers to make him qualify for a year. In 1972 he was appointed Somerset's

player-coach, and became the mentor of the club's thrilling new generation until

his refusal to kowtow before committee men led to a row in the toilet with the

club chairman, and then the sack. He had already settled in his wife's home town

of Neath and now he moved to Glamorgan, where he played for a while in 1977

before concentrating on the job of cricket manager, a rather thankless task, until

1983. Then, much more happily, he became director of coaching for the Welsh

Cricket Association, a job he held for 23 years. Cartwright remained in charge of

the Under-16s until he had a heart attack while shopping; he died a few days

later. Generations of youngsters will remain grateful to him: "He always had time,

always had faith in me," said Ian Botham. But nothing will match the admiration

of his contemporaries: "Tom was a master of his craft," wrote David Green. "His

incredible accuracy caused some people to classify him as 'negative'... I cannot

see how you could be negative if you have five close catchers and bowl every

ball at the stumps."