What Rahane's numbers don't tell you

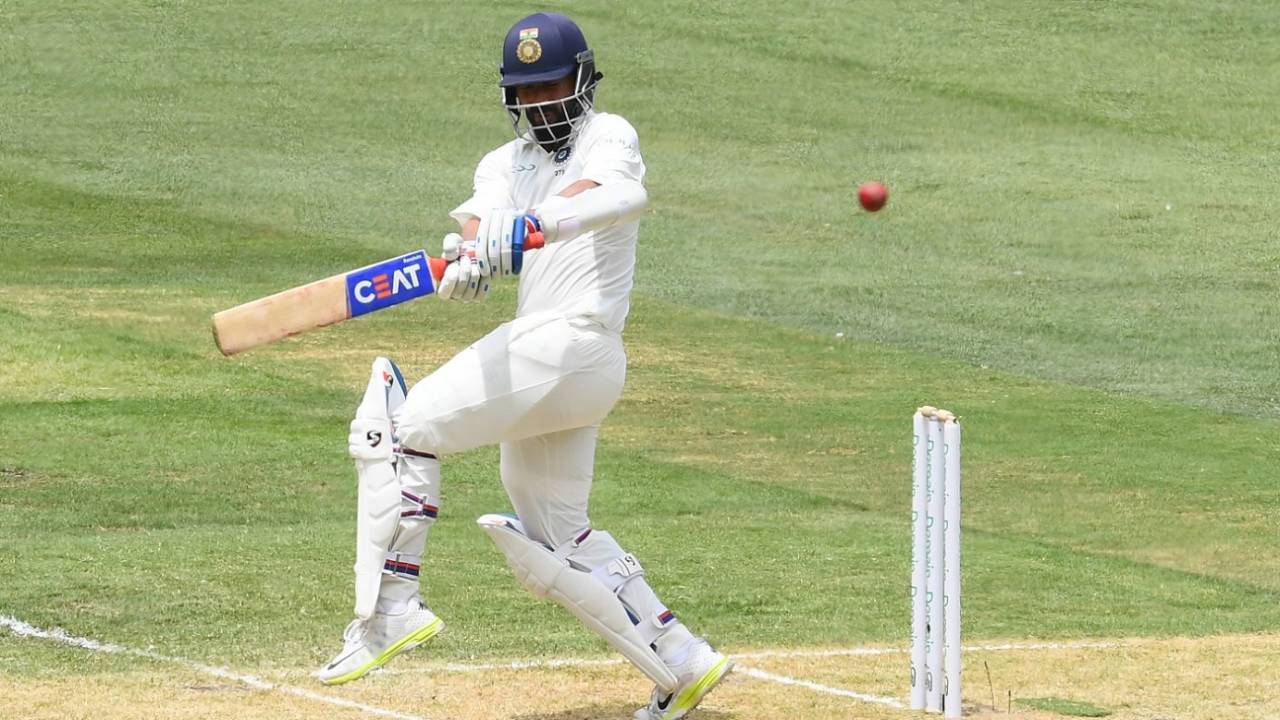

India's No. 5 had hit his lowest point at the start of the England tour last year, but has his utility to the world's top Test team been understated?

Karthik Krishnaswamy

29-Jan-2019

Getty Images

There are unplayable deliveries, and unspeakably bad shots, but most dismissals fall somewhere between those extremes. Sometimes, there are mitigating factors that muddy even the apparently extreme ones.

Take Josh Hazlewood's dismissal of Ajinkya Rahane in the fourth innings in Perth: a full, wide ball, a flat-bat drive, hit hard but in the air, straight to point.

Watch the side-on replay, and look where Rahane's feet are. His initial movement is back, and at one point his back foot is almost halfway back in the crease while his front foot is on it. Then his front foot moves forward, a fraction late, and he only manages to press it down about six inches in front of the crease. His weight is leaning back as he plays the shot, ensuring he'll struggle to keep it down.

In isolation, it's just a poorly executed shot, but look at the three balls that preceded the wicket ball - a bouncer that flies past Rahane's head, eluding his attempted hook; another short one that hits him on the thigh guard; and a length ball, described thus on ESPNcricinfo's commentary: "good length, he hangs back but defends comfortably enough".

These are the kind of clues that top bowlers pick up, and Hazlewood must have noted Rahane hanging back, perhaps with the short ball on the back of his mind - several deliveries were also climbing unexpectedly off this pitch - and felt this was the time to slip in the full, wide tempter.

Perhaps another batsman, a more in-form batsman, would have put the preceding balls behind him and watched this one better, judged its length better, moved forward more decisively, and either driven it along the ground or left it alone, in either case making a more informed choice.

Rahane wasn't in that sort of form, he had been searching for it for most of the last two years. In that period, he had gone from being India's most consistent batsman across conditions - with centuries in six of the eight countries he had batted in, 90s in the other two, and an average above 50 both home and away - to being a maker of useful small scores rather than match-defining hundreds. His Test average, over those two years, had dropped from the low 50s to the low 40s.

Rediscovering form, of course, isn't entirely up to the batsman. As in football, as Jean-Paul Sartre famously observed, everything is complicated by the presence of the opposite team. England and Australia did everything in their power to complicate Rahane's search for form.

Getty Images

On his first tours of the two countries, Rahane had been a far more confident and assertive presence at the crease. He judged length supremely well on the 2014-15 Australia tour, where he scored 399 runs at an average of 57.00 and a strike rate of 63.53. On that tour, he scored 70 off 72 balls when the fast bowlers pitched it full, as per ESPNcricinfo's ball-by-ball data, and 71 off 53 when they pitched it short. He treated the Australian fast bowlers with respect when they bowled the in-between lengths, scoring 110 off 279 balls pitching either on a good length or short of good length.

These numbers showed what made the 26-year old Rahane such an exciting talent. He had the defence, and he had all the shots, off front and back foot. He knew when to defend and when to play those shots. He scored hundreds at Lord's and the MCG, lofting James Anderson back over his head and tennis-swatting Mitchell Johnson wide of mid-on.

The 30-year old Rahane still had the same component parts, but he wasn't seeing the ball quite so well, and his eyes, hands and feet weren't working quite as smoothly as a collective unit. And the bowlers were making him work a lot harder for his runs.

Let's begin in England. At the start of that tour, Rahane had looked utterly bereft of confidence. At Edgbaston, he was the picture of uncertainty, his dismissals in both innings the result of being trapped in no-man's land: between leaving and playing in the first, between cutting and punching in the second. At Lord's, he was twice out feeling for the ball, hanging his bat out limply, away from his body, neither attacking nor defending.

Lengths England's quicks bowled to Rahane•ESPNcricinfo Ltd

By then, Rahane had made 132 runs in his last 12 Test innings, at an average of 11.00. This stretch included a horror home series against Sri Lanka at the end of 2017, in which he averaged 3.40, and a tour of South Africa where he spent two out of three Tests on the bench.

The runs began to flow after Lord's, though not in the kind of comic-book burst of cathartic hundreds that would have made this a simpler story to tell. Rahane was still working his way back into form, and was therefore a more circumspect batsman than he had been the last time he had visited these shores. In 2014, he had scored 85 off 83 balls when the fast bowlers had pitched it full. In 2018, he made 57 off 87.

And while he was scoring a little quicker against bowling that was even slightly short - his strike-rate against short and short-of-good-length deliveries was up from 44.44 to 53.85 - England's quicks adjusted and bowled markedly fuller lengths to him. From 55.44 in 2014, the percentage of balls they landed on a full or good length rose to 77.80 in 2018.

In particular, they bowled a lot more on a traditional good length, up from 36.96% in 2014 to 59.75% in 2018, and it paid off. Five of Rahane's seven dismissals to pace on this tour were off good-length deliveries. He had been dismissed seven times by the quicks in 2014 too, but those dismissals were distributed fairly evenly among the lengths - he was out twice to full balls, twice to length balls, twice to short-of-good-length balls, and once to a short ball.

Rahane found runs harder to come by against the quicks in 2018 than in 2014, his strike-rate dropping from 45.87 to 42.32, but he was also marginally harder to dismiss, getting out once in 69 balls, roughly, compared to once in 66 balls in 2014. By the end of the series, his average against pace (29.14) was, in fact, just a run short of what it had been in 2014 (30.14).

The big difference came against spin. In 2014, England were only just beginning to turn Moeen Ali from a part-time offspinner to a bowling allrounder. The Moeen of 2018 could still be a frustrating figure in subcontinental conditions, where the pitches were supposed to help him prosper, but he was a genuine threat at home. He also benefitted from made-to-order conditions in one of the two Tests he played in the 2018 series, in Southampton.

Rahane v Moeen in 2018 was a markedly different contest to Rahane v Moeen in 2014. In 2014, Rahane scored 83 off 127 against Moeen while being dismissed twice. In 2018, he scored a mere 19 runs off 95 balls, and was out twice.

| Tour | Runs | Balls | wickets | Average | Strike rate |

| 2014 | 83 | 127 | 2 | 41.50 | 65.35 |

| 2018 | 19 | 95 | 2 | 9.50 | 20.00 |

Those numbers, however, are a little deceptive: 72 of the 95 balls Rahane faced from Moeen came during the fourth innings of the Southampton Test, when he scored 51 and added 101 high-quality runs with Virat Kohli after they came together at 22 for 3, in an ultimately failed chase of 245. Moeen was England's biggest threat in that innings, with his turn and bounce out of the rough. Kohli continued to try to drive him out of the rough, as only he can, while Rahane trusted his defence, and the two of them kept Moeen wicketless for 16.4 overs before he finally broke through. The target was just too far out of reach on that surface, but for those 42.2 overs of their partnership, Kohli and Rahane made India believe.

Lengths Australia's quicks bowled to Rahane•ESPNcricinfo Ltd

The story of Rahane v Australia was similar, except that he began the tour in better nick than he had in England. In the last three Tests in England, and two home Tests against West Indies, he had made three fifties in five Tests, and averaged 41.25.

He may, therefore, have prospered had Australia's pacers bowled full to him as often as England's did. But they didn't - from 17.52% in 2014-15, the percentage of full deliveries they bowled to Rahane dropped to 10.28. Their short-ball percentage also fell, from 12.90 to 9.09. On pitches that gave them more margin for error than the featherbeds of 2014-15 did, and against a batsman who wasn't quite in the same kind of form, they bowled better lengths more frequently.

Meanwhile, their spinner, Nathan Lyon, was now a world-class force. He still had the classic loop and dip that defined his bowling in 2014-15, but he also had greater knowledge of how to vary his speeds according to the conditions, and Plans B and C for times when batsmen went after him. In 2014-15, Rahane scored 113 off 192 balls from Lyon, while being dismissed three times. In 2018-19, he scored fewer runs (80) off more balls (210), while being dismissed the same number of times.

| Tour | Runs | Balls | Wickets | Ave | SR |

| 2014-15 | 113 | 192 | 3 | 37.66 | 58.85 |

| 2018-19 | 80 | 210 | 3 | 26.66 | 38.09 |

All this meant Australia's attack kept Rahane under pressure for longer when he batted on the 2018-19 tour. This pressure had some role to play in the manner of some of his dismissals - caught at second slip playing a loose drive off Hazlewood, reverse-sweeping Lyon straight to point, the Perth dismissal dwelt upon earlier. Twice, he was also out to unplayable deliveries - a shortish Lyon offbreak that crept through at shin height at the MCG; a snorter of a Mitchell Starc bouncer, from left-arm around, at the SCG.

And so it was that Rahane ended his tours of England and Australia with these numbers: an average of 27.88, four fifties, no hundreds. They don't look great at first glance, but don't forget the key contributions he made along the way. His partnerships with Kohli at Trent Bridge and the Ageas Bowl were some of the highest-quality passages of play of the England series, featuring great know-how and purity of technique. In the second innings in Adelaide, he helped Cheteshwar Pujara shut the door in Australia's face, and if his dismissal off a reverse-sweep looked ugly, it was a shot played when India were looking for quick runs. On an unpredictable Perth pitch, his 51 could have - particularly if India hadn't played four No. 11s - helped India take a first-innings lead, and who knows what might have happened thereon?

In any case, given that his career probably hit its lowest point at Lord's, Rahane's tours of England and Australia begin to look less like a disaster and more like the first stirrings of a batsman recovering his lost poise, always against top-drawer attacks and almost always in challenging conditions. Along the way, he played an understated role in helping solidify India's place at the top of the Test-match ladder.

Karthik Krishnaswamy is a senior sub-editor at ESPNcricinfo