The forgotten men of 1991

Two players who were taken along to make up the numbers on South Africa's first tour after readmission look back, 20 years on

Firdose Moonda

15-Jul-2011

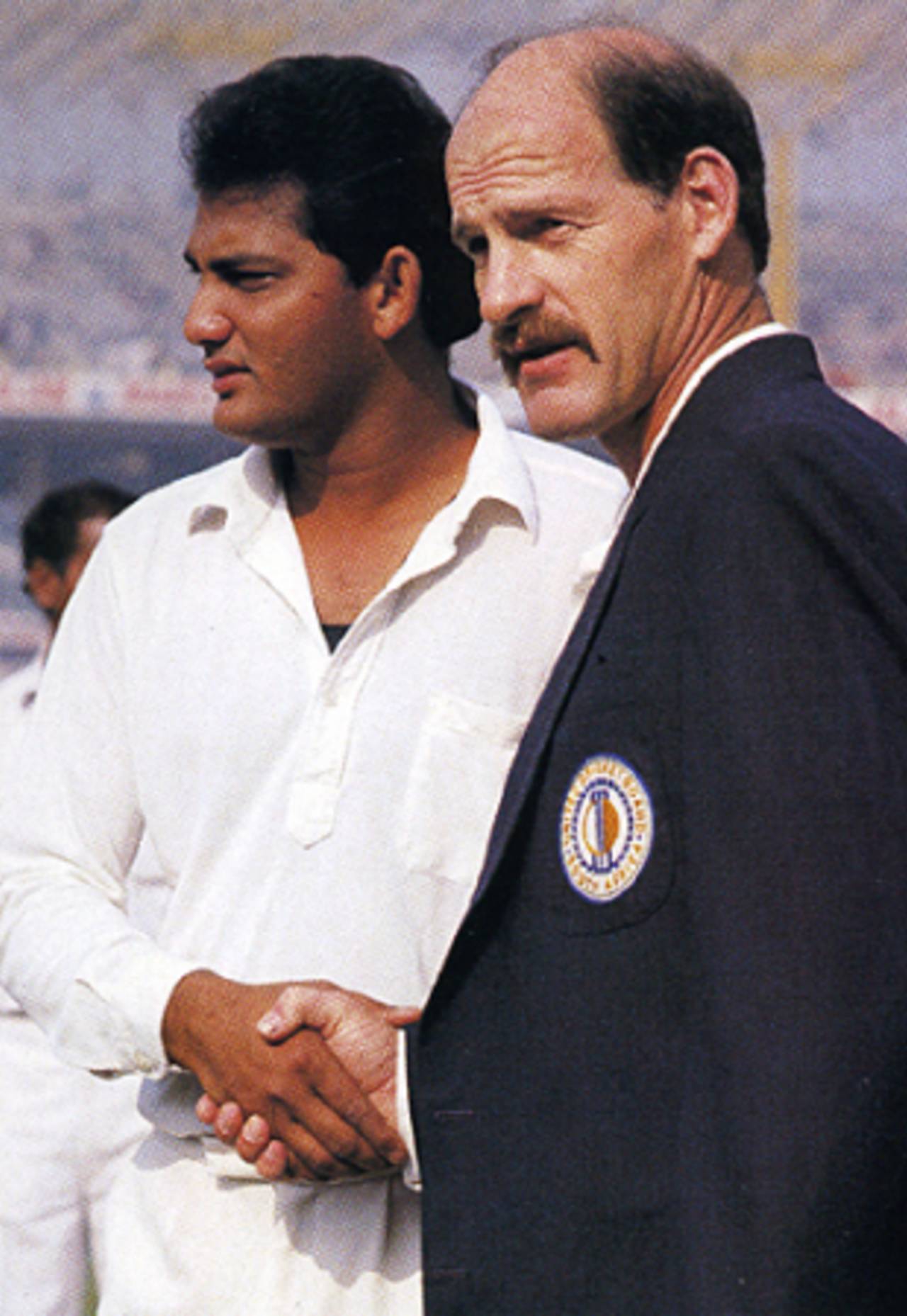

Mohammad Azharuddin and Clive Rice at the toss before the first ODI in 1991 • David Munden/Getty Images

Hussein Manack and Faiek Davids are not two names that are immediately associated with South Africa's readmission into international cricket. But 20 years ago, when the country's cricketers made their historic trip to India, Manack and Davids were part of the touring party. Together with Hansie Cronje and Derek Crookes, they went as non-playing, development members of the squad, but unlike Cronje and Crookes, they did not go on to have international careers.

The three-match series against India came barely a month after South Africa was readmitted as a Full Member of the ICC, and less than a year after unity, when the white South African Cricket Union (SACU) merged with the non-white South African Cricket Board (SACB) to form the United Cricket Board (UCB). Manack and Davids played under SACB but neither imagined he would be part of the first international sporting event the country participated in since isolation, especially since there were no plans for a cricket tour.

Even the 1992 World Cup was initially thought to be soon to reintroduce South Africa to the world stage. It was only when Pakistan pulled out of a scheduled visit to India that the door opened for South Africa to step in, and they were given just a week to get there. In those few days, a private plane was secured, hotels were booked and a squad was selected - a squad of 14 white players. That's when it occurred to administrators that something didn't quite fit.

"The President of the BCCI, Madhavrao Scindia, phoned me to say that since we sending an all-white team, questions would be asked, so we decided to take four development players," Ali Bacher, then managing director of the UCB, said. Two of those players would be of colour, although identifying them would prove tricky.

Despite being prominent players in the SACB set-up, Manack and Davids were little known outside of non-white playing circles. With unity, came opportunities for them and others to be recognized, and players of colour were included in some of the early camps to find future international players.

"Faiek and I were invited to attend a single-wicket tournament in the Free State. Some of the country's top allrounders were there - Adrian Kuiper, Peter Kirsten, Hansie Cronje, Clive Rice, Anton Ferreira," Manack said. "After I had hit Clive Rice for a few sixes, I remember somebody saying to Ricey as we walked off, that Transvaal had found a future star."

Their names, like those of Yaseen Begg, a wicketkeeper, Yacoob Omar, an allrounder and Baboo Ebrahim, a left-arm spinner, were mentioned as players from the SACB leagues who may have futures in cricket. Cricketers of that sort were plentiful but unknown, whereas white cricketers had played county cricket and against the rebel sides, and thus ended up being selected for the '91 squad ahead of the Beggs and Ebrahims.

Peter van der Merwe, the convenor of selectors at the time, said that they went on the season's provincial records when picking that first squad. "We had so little time, we just went on previous performances and put a side together," he said. The SACB players did not come into consideration, as their matches were not even given first-class status at that stage, and their records, although some of them had been well kept, were not as easily accessible as the SACU players' information.

It was up to Rushdie Magiet, formerly a selector with SACB who was also a selector for the UCB, to have a major say in who the two players of colour who would make up the development contingent would be. "I knew the quality of Hussein and Faeek and I thought it would be a wonderful experience for them," he said.

Neither Manack nor Davids - who did not even own a passport when he was picked - expected the call up, and both had to wrestle with the idea of going because of the political message behind their inclusion. "It felt like being selected was an afterthought, because the side had been announced already," Manack said. "At the back of our minds we thought that this may be window dressing. But I spoke to my dad and people close to me and decided to go after considering the options. I could either stay here [in South Africa] and play in a Benson and Hedges night game against Border or go to India and be part of the first international tour after isolation."

Davids also had people close to him who said that he shouldn't be going. Although he understood their concerns, the opportunity to be a part of history was too good to pass up. "I didn't think that in my lifetime I would go on a tour with the national team to India, and in the end I believe I made the right decision."

Both boarded the plane, which was the first South African aircraft to fly over India, unsure of what lay ahead but excited to be involved. "We were well accepted but I did get the feeling that the other guys weren't sure what questions to ask us," Davids said of the reception. "There were never going to be any intense discussions." Manack felt a similar isolation. "The guys were friendly but there were times when it felt like being an outsider looking in, and that we were taken along just to give the whole thing legitimacy."

The pair, along with Cronje and Crookes, took part in training sessions and travelled with the team but watched the three ODIs from the sidelines. They understood that part of the reason for their inclusion was because they were identified as players for the future, not the present.

They enjoyed soaking in the atmosphere that only India could provide. "India was cricket crazy," Manack said. "Players like Tendulkar and [Sanjay] Manjrekar were worshipped. There was no place you could go without being mobbed by fans looking to shake your hand or get an autograph."

The week was magical, a unique experience for the two; but there was no fairytale ending. The journey the pair made did not pave a clear path for them to make the leap onto the international scene. Although the trip was, in Bacher's words, "a small start" to embracing transformation, it did not quite prove to be the catalyst for wholesale change.

Manack and Davids were both disappointed by what happened, and what didn't, on their return home. Although the trip was a breakthrough for South Africa and both said their families and friends, even the dissidents, "watched the matches closely", the situation on the ground did not change as quickly as they would have liked, not just for them, but for people from the communities they came from.

"We [players of colour] were treated as if they didn't know how to play the game," Manack said. "There were plenty cases around the country, of experienced first-class cricketers being batted out of position and not being given a bowl." Davids found that players of colour got the "feeling that you needed to prove yourself over and over again".

Those issues had ripple effects, which Manack said led to some cricketers of colour simply walking away. "Out of pure frustration and embarrassment, some black cricketers gave up the game." That led to a lack of players at provincial level, so the other selectors were unable to pick any for the national team. "It made it difficult for us because the guys weren't coming through at the level below international cricket," Magiet said. "For me, the problem was that lower down people had difficulty recognising the merit of the black player."

Manack and Davids were two who were recognised in some way, and went on to play more than 50 first-class matches each. They never made the leap to international cricket but have remained involved in the game. Manack is a board member at Gauteng, the union that operates out of the Wanderers, and Davids is the assistant coach of the Cobras franchise in Cape Town.

Both believe that in the 20 years since they were part of South Africa's readmission, things have changed for the better and will continue to do so. "I actually wish I had been born now so I could have the chances players have now,' Davids said, while Manack had a message for the mindsets. "I would like to see people of my generation who still can't bring themselves to support South Africa to start doing so because it is our country, and unless we take ownership of our national sides we will not be able to have a say or make a difference."

Firdose Moonda is ESPNcricinfo's South Africa correspondent