The old-world virtue of Younis Khan

There's something dated, and comforting, about the security he represents for Pakistan, and when he is gone they will be truly bereft

Osman Samiuddin

07-Aug-2014

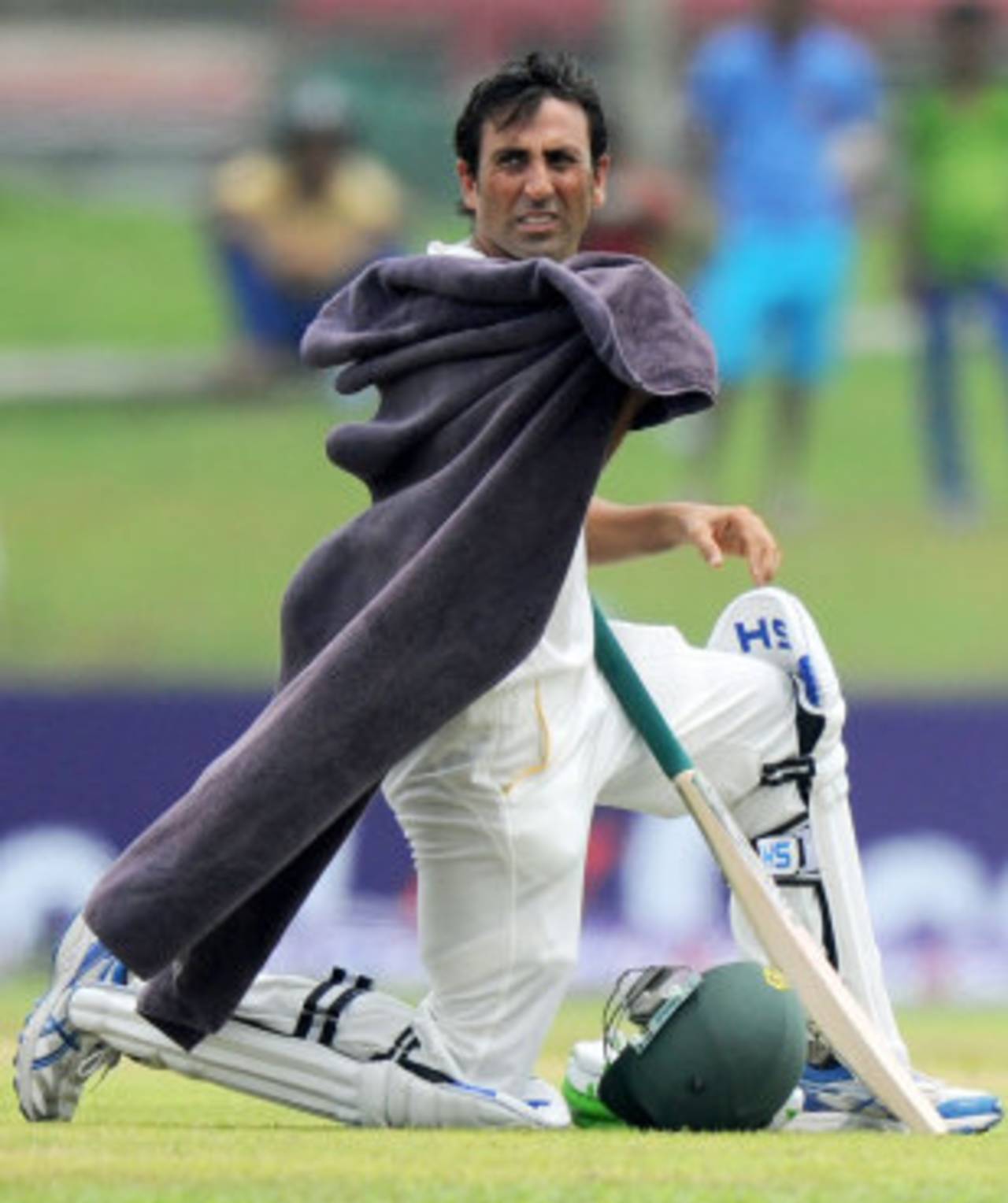

Security blanket: Younis Khan is the fading echo of a more wholesome time in Pakistan's history • AFP

Maybe I'm getting old but these days a Younis Khan hundred hits a sweeter spot than usual inside me. Somehow, when he scores a hundred the whole of Pakistan cricket feels like a more secure, comforting place. Hell, even the whole of Pakistan seems like a safer, more welcoming place. His hundreds are like a motion-sickness prevention pill, after which all the winding, roundabout insanity of Pakistan cricket matters less and less. Who's retiring? Who's in court? Who's the chairman? What's the domestic structure? Who cares? Younis is in.

I guess it's natural to start feeling like this now that he is coming to the end of his career. He wants to play in next year's World Cup and he may play on another year, maybe two, maybe even three, of Test cricket. But he's basically going to be gone soon. And then the one link Pakistan has to a past that it doesn't fetishise enough will be gone too: Misbah-ul-Haq is from the same space spiritually, he is older and the captain as well, but everyone knows Younis is the real institution in the side.

Don't get me wrong. Younis is very much a modern Pakistan product. But the ethos by which he has played his cricket - at every level - has always pre-dated the mores that have defined the period in which he has played. It is easy to imagine Younis as a cricketer in 1970s Pakistan; on the verge of superstardom, fighting for the economic rights of his comrades, nobly tending to local cricket. Some time ago he was talking about starting up a grassroots club in Karachi, where he could breed a certain kind of cricket culture - the kind that he represents. Who does that anymore, especially when it is more profitable to buy a franchise? He still turns up for his domestic side as often as he can, and his excursions into domestic cricket abroad have always been in the four-day formats. If Pakistan ever does get serious about setting up a players' association, you can be sure he will be right at its centre.

Even the stories involving potential violence from his early career sound somehow safer now. He used to travel to his Karachi club, the legendary Malir Gymkhana, through conflict-ridden areas of Karachi, on crowded buses that were lucky not to be struck by bullets. The city's inflammability of that era I could at least understand: to be in danger, generally you had to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, between warring political parties or ethnicities in specific areas. There was order to that, even if it was bloody and brutal. Now it feels like the whole country is in the wrong place at the wrong time. The violence is bloodier, more brutal, and worst of all, random.

That sense is what I've gradually come to love most about Younis, that he is the fading echo of a more wholesome time. I sense it every time he bats with an Asad Shafiq or an Azhar Ali, for whom he isn't so much a batting partner as a counselor or a guide. Much more than run-making, he is teaching them about resilience. He is teaching them how to soak up the pressures of the insecure early existence of a Pakistan international, and how to survive an environment where a young player is not an asset but a cheap, expendable resource.

He had to learn it himself. He had to learn - though he still hasn't fully - which battles to pick and which to ignore. It wasn't until 2005, after all, that he became secure in the side, five years after his debut. That moment came after a Test hundred in Kolkata, when a realisation struck him: "Even if I didn't succeed," he said in an interview after that India tour, "it wouldn't matter. I've always wanted to play good cricket - I don't want to play more, but try and play with my dignity intact."

One day soon Pakistan will field a team in which nobody has played Test cricket in Pakistan, and that is when I think the virtue of Younis Khan will become clear

By modern measures, it's kind of ridiculous that he has only played 90 Tests in 15 years (Alastair Cook is beginning his 107th in eight years today). But back in 2002-03 few - including Younis - would have thought he would get even that many. Perhaps that is what he wants Shafiq and Azhar to understand the most. He has lived through 15 of the grimiest years in Pakistan's cricket, a fair shit-storm of an age, and sure, there's a spot or two on his whites, but they are mostly still white. If he can teach Shafiq, Azhar and anyone else how to do that, it will really be something.

This latest hundred itself? It hardly mattered how it was made, except that it progressed like many of his hundreds, like the trajectory of his career, in fact: a becalmed start, fortunate to survive, but increasingly assured as it went on. I used to think he was too fidgety and skittish to ever be the rock that Pakistan needed, forever in perpetual, slightly neurotic motion at the crease. Mohammad Yousuf and Inzamam-ul-Haq, by contrast, were so still that they were obviously gifted. But Younis managed just fine. Statistically at least he is getting to be the equal of both.

In my older and more partial moments (usually when considering his slip catching and the fact that he stands a couple away from becoming the first Pakistani to 100 Test snaffles) he may even sneak ahead. He saved Pakistan on the first day, as he has done, not always, but enough times for all of us to feel sure and secure around him.

I'm going to bottle up that glow because one day soon Pakistan will field a team in which nobody has played Test cricket in Pakistan, and that is when I think the virtue of Younis Khan will become clear. For a team that has no home, the late-career hundreds of Younis Khan have felt like home. Only when he's gone will Pakistan be truly homeless.

Osman Samiuddin is a sportswriter at the National