Following the Test against Sri Lanka

in Sharjah, the signature win that he needed, there has been discussion of Misbah-ul-Haq's record as captain, with some

even suggesting he could possibly contend for the title of the second-best captain in Pakistan's history. Statistically there is certainly a case to be made, and the context provided by those who came before him can only exalt his work, but despite his achievements thus far, the Mount Rushmore of Pakistani captaincy already has three men, and none of them is named Misbah.

The first name, obviously, is

Imran Khan. The second belongs to a man who, spiritually if not actually, preceded him:

Mushtaq Mohammad. And the third might be the most important man in Pakistan's cricket history:

Abdul Hafeez Kardar.

Back in 2011 there was a small debate over the renaming of Gaddafi Stadium following the Colonel's death. At the time Osman Samiuddin

reasoned that it would be most fitting to name the stadium after Kardar. His argument then was based more on Kardar's work after he retired, but his playing career - or rather his captaincy alone - could have made a worthy case too.

Some context first: it took India 40 years to win a Test match against every other Test-playing nation at the time, when they beat West Indies

in Port-of-Spain in 1971, their first win against them in 25 attempts. New Zealand too had to wait until the 1970s to complete the set. It took Sri Lanka almost two decades of trying, and neither Zimbabwe nor Bangladesh have yet achieved the feat. West Indies had unqualified early successes - they beat Pakistan, India and New Zealand in their first bilateral series, and it took them only half a dozen Tests to win for the first time against Australia and England.

Pakistan too were impressive early. They won a Test match

against every other nation (bar South Africa, who they did not play) within six years of their first Test match. More remarkably, they won at least one Test match in their first series against each of those teams. They completed their set in 1958, against West Indies, in a series that was also to be Kardar's last (he had captained Pakistan in every match until then). During this time he had drawn a series in England, and won against Australia. What happened after Kardar was what is supposed to happen to new entrants. What happened under Kardar is unprecedented.

Much like the man who would replace him as Pakistan's greatest ever captain, Kardar was an Anglicised Oxonian, supposedly a "born leader". A Test player before independence, he, like

Fazal Mahmood and Imtiaz Ahmed, was selected to the Indian squad for the 1947-48 tour to Australia. All three declined, forsaking international cricket during some of the best years of their careers in the hope that Pakistan would play Test cricket one day. All three, predictably, would be part of Pakistan's first Test XI in October 1952.

Most accounts paint Kardar as fiercely nationalistic and of the belief that the stick was preferable to the carrot. One could argue that almost every successful Pakistan captain since Kardar has tried to imitate the model he created. Of course, Kardar was helped by external factors too. He had the advantage of taking over the captaincy of a newly independent country and all the positives (automatic motivation and team spirit) that come with it. Pakistan could also select players, like Kardar himself, from an established cricketing tradition rather than needing to forge one from scratch - and therefore had something rare for a new entrant, a genuinely world-class bowler in Fazal. But even so, Kardar's achievements as captain are extraordinary.

And considering his resumé, it was unsurprising that he ended up running the PCB (or the BCCP as it was known then). By the time he took over in 1972, Pakistan cricket - on and off the field - was in the gutter. The cricket board "had been for years a homeless entity, existing out of a trunk and then an office in Karachi's National Stadium", as Samiuddin wrote, and the national team had finished the 1960s with just

two Test wins. Kardar took the board to Lahore and began the process of the professionalisation, thus setting up the platform that a generation of talented players required. Pakistan spent the first half of the '70s regaining respect, but their fortunes only improved slightly on the field - they became more difficult to beat, but winning was still an alien concept; and when they did

get close, the gods weren't kind to them.

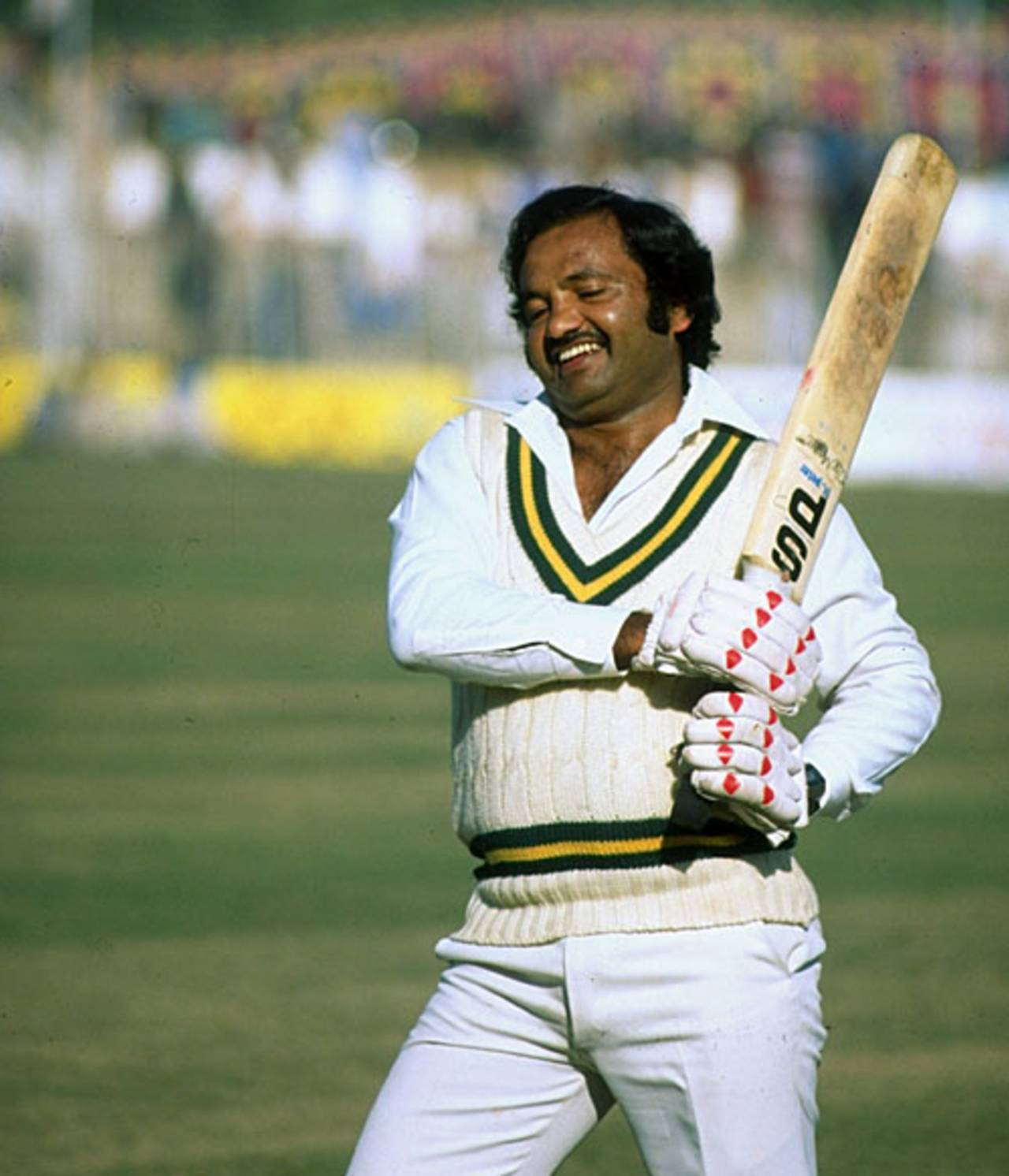

Then in 1976, Kardar appointed Mushtaq Mohammad - in his 18th year in Test cricket - captain of the national team for the first time. In the years since Kardar's retirement, Pakistan had won only five of their 53 matches in 18 years (yet bizarrely still had a

win-loss ratio of 1.0 or better against two of the five teams they played).

But Mushtaq's appointment was to herald the dawn of a new age. His

first match as captain was to be the exact moment when the era began. The top run scorer in that match was a debutant by the name of Javed Miandad. The leading wicket-taker was Imran Khan, who until then had picked up just five wickets in four Test matches. Under Mushtaq the generation of the early '70s finally found the consistency that they had lacked before. Each of Majid Khan, Zaheer Abbas and Asif Iqbal averaged over 49 under him; add Mushtaq himself, Wasim Raja (who too averaged over 40) and the prodigy Javed (who averaged 78), and Pakistan had the closest that they have ever come to a golden age of batting.

But Mushtaq's greatest achievement, apart from inculcating a winning mentality, was the change in Pakistan's bowling set-up. In the years since Kardar retired, more than 45% of Pakistan's wickets had been taken by spinners. Under Mushtaq less than a third were taken by spinners, with more than half being accounted for by Imran and Sarfraz Nawaz alone. So one could argue that Mushtaq Mohammad is the father of all that we consider stereotypically Pakistani: the bullying strokeplayers and the fast-bowler-heavy attacks of the next quarter century. Pakistan would go on to

win eight and lose only four matches under Mushtaq, winning a Test (and drawing a series) in Australia for the first time, and winning a series against India for the first time too.

Eventually Kardar left because of altercations with Mushtaq, and Mushtaq's legacy has been gobbled up - consciously or otherwise - by the school of Imran. Thus if they were to be sculpted on to a Mount Rushmore they would probably all be facing away from each other, but what could be more Pakistani than that?