A giant of his time

A colossus, both as a player and a personality, he was a barracker's delight and Australia's MVP

Gideon Haigh

19-Sep-2009

The most identifiable man since WG Grace • The Cricketer International

Three significant artefacts on display celebrate Warwick Armstrong in the Australian Cricket Hall of Fame, to which he was elected in January 2000. His Crockett bat was there but the other two beggar belief. One is a pair of boots, white kid leather with iron spikes, possibly of the "Warwick Armstrong" brand, marketed by W Abbott & Sons of London's Ludgate Hill. Over a foot long and seven inches wide, they resemble small canoes, or the footwear that anchors divers to the sea-bed. The other is the shirt, perhaps the most famous of its kind anywhere. It is not of flannel but of wool, probably designed for the northern hemisphere, and measuring over three feet by 33-and-a-half inches it would hang on most people like a smock. Fitted today on a large tailor's dummy, it seldom fails to arrest passers-by: how, one wonders, can a man so mountainous ever have played cricket?

This is a reflex response, of course, conditioned not only by what we feel cricketers should look like, but what people should. The parameters of what we now define as "fit", indeed, are extremely narrow. We regard the tapered shapes of our Olympic athletes and swimmers as the embodiment of health and grace - yet, strung to their pitch of perfection, how frequently are they laid waste by the slightest cold or virus.

Maybe Warwick Armstrong was not "fit" as we understand it. He smoked, he drank, he carried a top weight of 140kg and probably would have puffed if asked to run a hundred yards. Yet, studying his achievements in the year running from 1919 to 1920 in first-class cricket alone, our preconceptions are challenged. He would bat 52 times, scoring 2282 runs at an average of almost 56. He would bowl 5420 deliveries, claiming 117 wickets at a cost of 15.47 runs each.

For the purposes of comparison, consider that in Test, first-class and one-day cricket during the year from October 1999, Steve Waugh batted 42 times, and Shane Warne bowled 4572 deliveries. Armstrong, in other words, did more than both put together - going on 42 years of age, what is more, and despite two recurrences of malaria. The comparison is inevitably far from perfect, but the arenas on which they played are of equivalent size and the pitches have always measured 22 yards. Armstrong was, then, "fit", in its original sense: preternaturally strong and durable. He was "fit" to do what he had to.

In this respect, Armstrong's weight is immaterial: it curbed his effectiveness not a jot. A newsreel of him batting and bowling in all his vastness against Surrey at The Oval in June 1921 is surprisingly impressive: although his crouching stance is ungainly, the few strokes featured are fluent and wristy, and the legbreak action could barely be improved on. Yet, precisely because Armstrong's bulk has become, 80 years later, almost the only reference point to him that we retain, it invites our consideration.

Armstrong's post-war eminence was not despite his bulk, but in large part based on it. "Armstrong's very immensity as a cricketer and as a personality," felt the Age, "makes him extremely popular with the whole cricketing public." This suggests that either moral judgments about weight were not being made in Australia and England or that Armstrong's post-war appeal was based on something else, that as a growing point in a shrinking world he bucked the trend. Because settling flesh in no way compromised his effectiveness, perhaps, he became a glorious exception to the new rules. "He is a living proof of the truth," asserted EHD Sewell in the Captain, "that size does not matter so long as the individual concerned is active."

In the hundreds of thousands of words written about Armstrong's cricket, it is surely of significance that he was never referred to as "fat" - wherever size is at issue, he is always "big". He evoked another age, and another champion still fresh in the memory; as Edmund Blunden put it in Cricket Country: "If I were to write a dictionary of cricket, I would enter in the index: Armstrong WW, see Grace WG, and Grace WG, see Armstrong WW." Frank Iredale, who had played against both Armstrong and Grace, saw similarity even in their mannerisms: "He does a lot of things that WG used to do, for instance, when he looks like missing the ball in the field, he grabs it at the last moment and seems to say: 'I know it will surprise you.' He had got the old man's happy knack of picking out the vacant spots in the field, and also the irritating habit of turning the ball out of his wicket just when a bowler thinks he has got him... He is the last link with those great men that kept the flag flying prior to 1902."

Armstrong's unbeaten 162 for Victoria against South Australia in January 1919 was a vital validation, both for himself and for onlookers. Those who might have harboured doubts about a cricketer of such tonnage rushed to praise and explain. "He gets himself into rare physical condition," wrote Jack Worrall in the Australasian, "and can bat and bowl all day, irrespective of how fierce the sun's rays may be. It seems safe to prophesy that he has many years of usefulness yet to his credit."

In the hundreds of thousands of words written about Armstrong's cricket, it is surely of significance that he was never referred to as "fat" - wherever size is at issue, he is always "big"

"Short stop" of the Leader thought he had imbibed "the elixir of perpetual youth": "Warwick Armstrong shows no diminution of his magnificent powers, and for a man of his colossal physique is wonderfully active. The secret of his condition is that he regularly exercises all through the winter by indulging in boxing and football on the Melbourne ground. He is of the build for a 'white hope' and would match any of the big Americans such as [Jess] Willard and [Fred] Fulton in size if not science."

The press now relished writing about Armstrong. Having found his cricket hard to describe before the war, journalists found his displacement a far richer source of inspiration, especially in England. The Observer's Harry Altham saw him historically: "In bulk greater than any cricketer since Alfred Mynn, the captain is today as great a batsman as he ever was, possibly in a real crisis the greatest in the world." The Daily Mail's Herbert Henley saw him whimsically: "Anyone meeting Armstrong in the street might imagine him a retired merchant with a rooted objection to exercise of any form and a taste for cigars and good living." Most famous is Edmund Blunden's word picture in Cricket Country: "He made a bat look like a teaspoon, and the bowling weak tea; he turned it about idly, jovially, musingly. Still he had but to wield a bat - a little wristwork - and the field chased after the ball in vain. It was almost too easy."

Perhaps even better were the lambent lines of Neville Cardus, a brilliant young wordsmith recently baptised "Cricketer" in the Manchester Guardian: "Armstrong - how well the name befits his composition!... He is elemental, of the soil, the sun and wind - no product of the academies. Nature has by herself fashioned him - he has grown on the cricket field, like the grass. Someone has called him a cricketing Falstaff. The simile will not do. There is no kind of alacrity about Armstrong, no apprehensiveness, nothing 'forgetive'. His composition is of the humours, shrewd instincts and most likeable flesh... Australian cricket is incarnate in him when he walks from the pavilion, bat in hand. Consider the huge man's bulk as, crouching a little, he faces the bowler. He is all vigilance, suspicion and determination. The bat in his hand is like a hammer in the grip of a Vulcan."

There is some powerful imagery here: boxers, businessmen, characters from fact and fiction, even Roman gods. Yet the metaphors that clung were maritime: it appears to have been shortly after the coming of peace in 1918 that Armstrong collected a nickname to accompany him for the remainder of his career.

For some years before the war, both "Felix" and "Short Stop" had enjoyed describing Armstrong as the "Leviathan of Cricket", a popular appellation of the period for anything large. During the war another leviathan then hove into view: the world's largest ocean liner. More than 325 yards long (300 metres), displacing 55,000 tonnes and capable of holding 3300 passengers, she was originally the Hamburg American Line's Vaterland. Interned in New York after her maiden voyage and redeployed as the troopship Leviathan, she then returned to Atlantic service under that name. This may explain why, too much of a mouthful for laymen, the "Leviathan of Cricket" appears to have been simplified as "the Big Ship".

The nickname was certainly in use in the aforementioned match against South Australia, for Victor Richardson recalled it tripping from Bill Whitty's lips when Armstrong was dismissed in the second innings: "Bill Whitty was in great glee. He rolled over and over on the grass in his delight. I can still see him. As Armstrong lumbered from the wickets - and 'lumbered' described it best - Bill called after him: 'And the Big Ship sailed safely home again.' He lay there laughing until I thought he would swallow his tongue. It was the first time I had heard Armstrong called 'the Big Ship'. I thought how appropriate it was... 'Big Ship' he looked as he made his way home that afternoon."

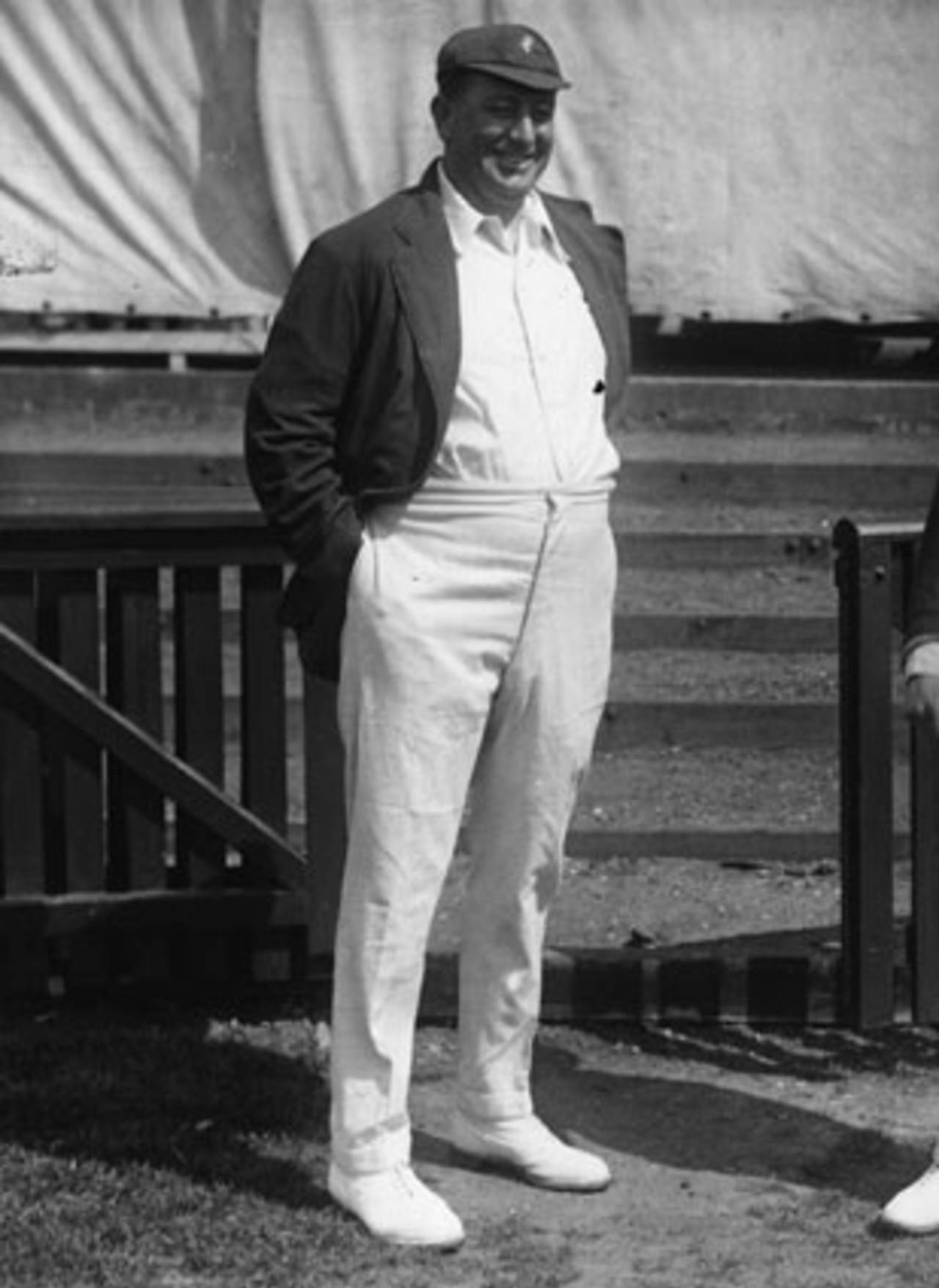

Bat as teaspoon; note also how small the cap looks•Getty Images

Appropriate indeed. Before the war the great Atlantic liners had been symbols of national pride and accomplishment; after the war they would be fungible currency in the settlement of Germany's war debts. Australia, of course, had no such nautical expression of itself, but it did have in Armstrong the largest cricketer afloat. The epithet does not seem to have been used in print until December 1920, when Leslie Poidevin profiled Armstrong in the Sydney Morning Herald: "He is, in fact, the 'big ship' of our cricket today - in physique, performance and in possibilities." But variations on the theme soon proliferated. When Armstrong almost fell over while trying to field the ball at the Adelaide Oval in January 1921, Charlie Turner of Sydney's Sun reported an onlooker's interjection: "The wreck of the Armstrong!"

Not everyone overlooked Armstrong's corpulence. He was built for the barrackers' sport. Ray Robinson, just old enough to have seen Armstrong as Australian captain, recalled him being "subjected to barracking as heavy as his own tread". In On Top Down Under, Robinson wrote: "If he failed to reach an edged ball, they would yell, 'You big jellyfish' and coarser terms of endearment."

Australian spectators have always induced strong reactions; those of Armstrong's career were no exception. England's Drewy Stoddart had deplored "the evil of barracking", after his tour of 1897-98, as "no good to man or beast"; South Africa's Percy Sherwell had opined after his 1910-11 visit that "to play without the accompaniment of cheers and groans and advice gratuitous would be to eat an egg without salt". English legspinner Cec Parkin found fielding before a packed Australian house 80 years ago an experience like no other: "A crowd of 50,000 sit in the terrific sunshine. To see a Test match, Australians have been known to travel a thousand miles. Work is suspended in the afternoons, and a contrast with the packed ground is the quietness of everywhere just outside. Sometimes when the heat is unbearable you will see thousands of spectators sitting in shirtsleeves, even without their waistcoats. Boys go round the field all day long selling ices and iced drinks and there is a great demand for 'tonsil varnish'. If you make a mistake, you have to go through it. I remember during the first Test match I somehow got fielding in the long-field. The crowd just behind me kept shouting, 'What's your name, cocky? Who said you could play cricket? It's a rumour.'"

In defending local mores, apologists for Australian crowds viewed it as significant that they were prepared to chaff their country's elephantine captain. After the second Test, Melbourne's Truth spoke out on the locals' behalf: "Perhaps the most predominant notes in Australian barracking are cheerfulness and impartiality... How often during the two Test matches when Armstrong happened to misfield a ball was he told to 'get work', yet Armstrong is the idol of the crowd."

The irony is that the same bulk that made Armstrong barrackers' bait was also his best defence. His feelings as a skinny youth might have been injured by the imprecations of St Kilda supporters, but nobody intimidates a man of 6ft 3in and 140kg. Armstrong had taken a leaf from Monty Noble's book - his advice to cricketers about the barracker was to "betray no sign that you even know he is there" - and his very size made barracking seem mere noise: as effectual, in English writer Alan Gibson's phrase, as "a peashooter on the Great Pyramid".

If anything, the larger Armstrong grew, the more wilful he became in the face of spectators' interjections. Having refused to bowl at Trent Bridge in May 1905 while the crowd was in uproar, he actually sat down on the pitch at Old Trafford in July 1921 while awaiting the subsidence of jeering. Jack Fingleton recalled a flavoursome vignette from a Sheffield Shield match when Armstrong retrieved a ball from the fine-leg boundary: "The big fellow ambled out after it, recovered the ball and was raising his arm to return the ball when a spectator at his back shouted: 'Come on Armstrong! Throw it in!' Armstrong at once dropped his arm, walked slowly back to his position in the slips, then softly lobbed the ball back to the bowler."

In a thorough survey of opinion on barracking by the Herald during Victoria's MCG match with New South Wales at Christmas 1921, Edgar Mayne claimed that several visiting players had confided their reluctance to play again before such uncouth demonstrations: "Is it British fairplay for mobs to get on to one man?" Armstrong, the newspaper reported, was more defiant: "Mr Warwick Armstrong thinks that he gets most of the barracking while he is on the field. 'Perhaps they do it,' he said, 'because they know it has no effect on me.'"

Not everyone overlooked Armstrong's corpulence. He was built for the barrackers' sport. Ray Robinson, just old enough to have seen Armstrong as Australian captain, recalled him being "subjected to barracking as heavy as his own tread"

What did it mean for Armstrong, in a physical sense, to be such a huge man? You can approximate his experience by a simple experiment: if you weigh 70 kg, try piggybacking a person of the same weight. Hefting 140kg on a daily basis, let alone in the context of a cricket match, requires enormous effort. Profiling Armstrong for the Captain, Laurie Tayler revealed that in "in his native land he [Armstrong] perspires so much that a pool is often formed at the crease, which seriously interferes with the bowling on the wicket". The quotidian strain on legs and feet alone would have been enormous.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Armstrong's post-war dimensions is an effect evident in group photographs featuring him. His is the face and physique on which the eye naturally alights; even surrounded by team-mates, the Big Ship possesses an unmistakable magnetism. In the context of Armstrong's time, this identifiability is noteworthy. Even today it requires practice for a cricket spectator to distinguish between sundry white-clad figures. In an era when photography remained primitive and news was vested in word rather than image, it was still more difficult.

It was sometimes complained after the war - the Golden Age already taking on mythic qualities - that cricketers were more homogeneous, lacking their former individuality. In 1922's Cricket and Cricketers, Philip Trevor complained that not once between 1897 and 1914 had he ever needed a scorecard to identify batsmen; now they were all alike. But never at any stage in Armstrong's career was there a risk of misidentification, and post-war pictures of him scarcely needed captioning. The February 12, 1921 issue of Pals - "an Australian paper for Australian boys" - featured Armstrong on the cover beneath his Melbourne cap. That was all it featured, too: there was no name, no identification on the inside cover, not even on an article in the magazine concerning him. He was simply, totemically, there. Even in Scotland, when Australia visited four months later, the Watchman stressed that introduction was needless: "Armstrong is so big that he will be easily identified... Big, jovial, good-tempered but shrewd and obstinate (if necessary), Armstrong is a butt for those who like fun. To see him bend to pick up the ball - a mountain in labour - the mob chortles and Armstrong smiles. Not a bit does he mind being chaffed. Armstrong does not mind anything so long as his side keeps winning."

Gideon Haigh is a cricket historian and writer. Some articles in the Movers and Shapers series, including this one, were first published in Wisden Asia Cricket magazine in 2002