Would a code of honour help?

Experiments have shown the thought of a moral benchmark could be useful in preventing corruption

Rudi Webster

Nov 14, 2010, 3:08 AM

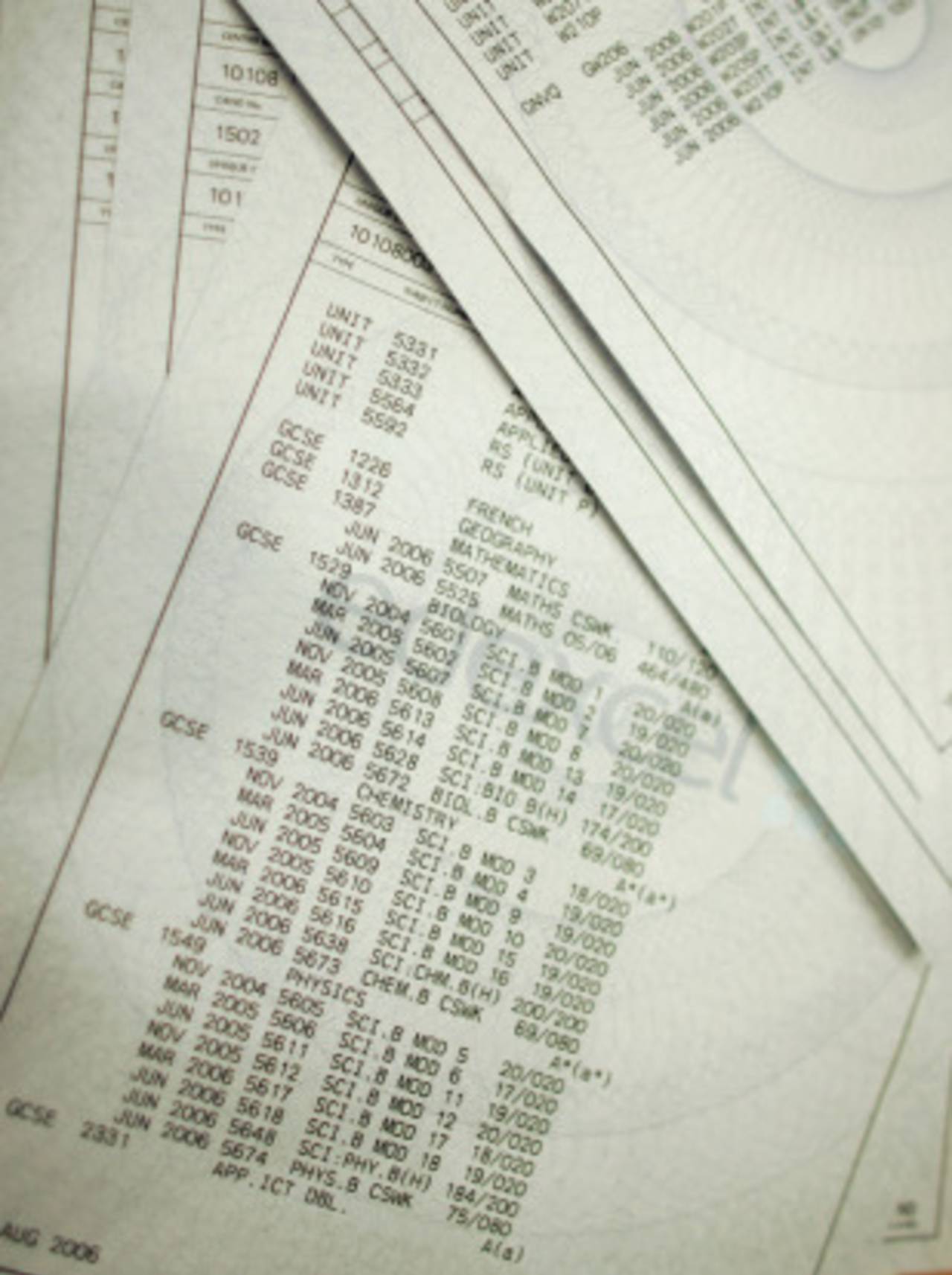

Experiments have shown that people are less likely to cheat if confronted with moral or ethical oaths just before they are tempted to commit the wrongful act • Getty Images

The alleged spot-fixing incident in the recent England-Pakistan series has raised many questions. How could young players get sucked into such an evil scheme? Could a simple thing like greed be the cause of such behaviour, or is the cause more complex? What roles did the players' background, age, education, financial status and culture play? And how might biological, psychological, socio-economic and moral factors influence the way they acted?

Though abilities, experience and the factors listed above are all important and give us clues about how a player is likely to behave, the most useful information comes from his motivation and goals, and the values and beliefs they represent. In motivation, the player chooses to behave in certain ways in exchange for rewards that he finds appealing. Some of those rewards are external - money, praise - and others are intrinsic: excitement, a sense of achievement. Players are motivated by a blend of extrinsic and intrinsic rewards, not just by money, and that mixture varies from one player to the other and from one situation to the next.

A player's behaviour is an interaction between him and the environment. The conduct of players found guilty of wrongdoing should therefore be judged not just in the context of their own environment but also in that of broader society.

How much cheating is there in today's society? Some will say that it is rampant. Dan Ariel, a behavioural economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) points out that in 2004 the total cost of all robberies committed in the USA was about US$525 million. But in the workplace, employees' theft and fraud are estimated at about $600 billion. That is much more than what all the career criminals in the USA could steal in their lifetime.

Other examples include politicians who accept gifts from lobbyists, physicians who make kickback deals with laboratories that they use, corporate executives who back-date their stock options to boost their final pay, and leaders and managers in sports organisations who use fraudulent practices to make money. Why are these white-collar crimes judged less severely than others?

A few years ago Ariel conducted a series of experiments at the prestigious Harvard Business School to get a better understanding of why people cheat. The experiments were set up to tempt students to cheat. Would the brightest and most privileged of American youth take the bait? They did. Ariel found that when given the opportunity, many honest students cheat. In fact, the majority did. He also noted that once tempted to cheat, the students did not seem to worry too much about the risk of being caught. On the other hand, if there was no chance of being caught, they did not become wildly dishonest.

In one of his experiments, he asked one group of students to write down the titles of 10 books that they had read in high school and another group to write down the Ten Commandments from the Bible, just before they started the real test. The results were surprising. The first group cheated but the second did not. He noted that in the second group there was no difference between the students who remembered just two of the commandments and the others who recalled most of them. This suggested that while the commandments themselves did not encourage honesty, the sheer thought of a moral benchmark did.

Ariel then repeated the experiment, but instead of using the Ten Commandments, he asked the students to sign a fictitious MIT Code of Honor, just before they took the test. The results were identical to those in which the Ten Commandments were used. There was no cheating. He later showed that professional ethics and professional oaths could act in a similar fashion to reduce dishonesty if read or remembered just before participants are tempted to cheat. He then stressed that once professional ethics declined it was extremely difficult to get them back. Is there a lesson there for the stakeholders in the game of cricket?

Being successful in life is as much about inhibiting negative impulses and saying no as it is about starting and maintaining positive actions. When tempted to cheat, the ability to pause and then say no is very important

Ariel described two types of dishonesty. The first type is related to the big-time stealing that is practised by career criminals. Match-fixing probably falls into that category. The second type is related to petty stealing by people who consider themselves honest - for example, pinching a pen at a conference, or stealing a package of soap or a towel from a hotel room. Spot-fixing could fit that type. We are very good at rationalising petty cheating as insignificant. In the same way, a player might rationalise as insignificant the request to bowl the odd no-ball at particular periods of the game.

But because of that small transgression a player could easily get caught in a cruel web cunningly constructed by handlers, who then control behaviour by fear, personal threats and threats to family.

We need to improve and strengthen current methods of reducing cheating in cricket. But, we must understand that external controls work in some cases but not in others. We must then design and implement effective strategies. Current research into dishonesty and cheating could help us in that respect.

We could start by repairing the erosion of ethical standards that has taken place in the game over the years. We could even ask all of the stakeholders in the game to sign a cricket Code of Honour that reflects the following: respect for the game and the environment in which the game is played, respect for authority figures, respect for the rights of players, and an awareness of responsibilities to country, sponsors, spectators and other stakeholders. As Dr Ariel's research has shown, intermittent repetition of that code might reduce the level of dishonesty in the game.

Our brains control how we think, how we feel, and how we behave. In recent years there has been a lot of scientific research on the workings of the brain. One of the pioneers of this research is Dr Daniel Amen, a psychiatrist who used scans of the brain, SPECT (Single Photon Emission Computed Topography) scans, to measure the blood flow and activity patterns of different parts of the brain.

One region of special interest was the pre-frontal cortex (PFC) of the brain, an area that deals with planning, forethought, motivation, impulse control and the modulation of emotions. Using his special imaging techniques, Dr Amen showed that abnormalities of function in the PFC were prevalent in murderers, criminals, robbers, rapists, paedophiles, wife beaters, child abusers, compulsive gamblers, thrill seekers and unfaithful spouses. These people share one common problem - the inability to inhibit negative impulses. Treatments are now being developed to address the problem of PFC dysfunction.

When enticed by fraudsters, cricketers have to deal with competing impulses. In general, healthy brains say no to negative impulses, but unbalanced brains do not. It should be noted that the PFC is not fully developed until the mid-20s.

In the next two decades, sportspersons might be asked to get routine SPECT scans to assess the state and function of their brains in an effort to identify abnormalities that might affect their performance and behaviour.

Being successful in life is as much about inhibiting negative impulses and saying no as it is about starting and maintaining positive actions. When tempted to cheat, the ability to pause and then say no is very important.

Former British prime minister Tony Blair was well aware of that when he said, "The art of leadership is saying no, not yes. It is very easy to say yes."

Dr Rudi V Webster is a medical doctor and a former cricketer. He did pioneering work in performance enhancement in Australia and worked with many of that country's best athletes and sports teams