Fearless Stan

McCabe at the crease was the personification of batting with haste yet no hate. On his birth centenary, we remember the batting genius

Christian Ryan

16-Jul-2010

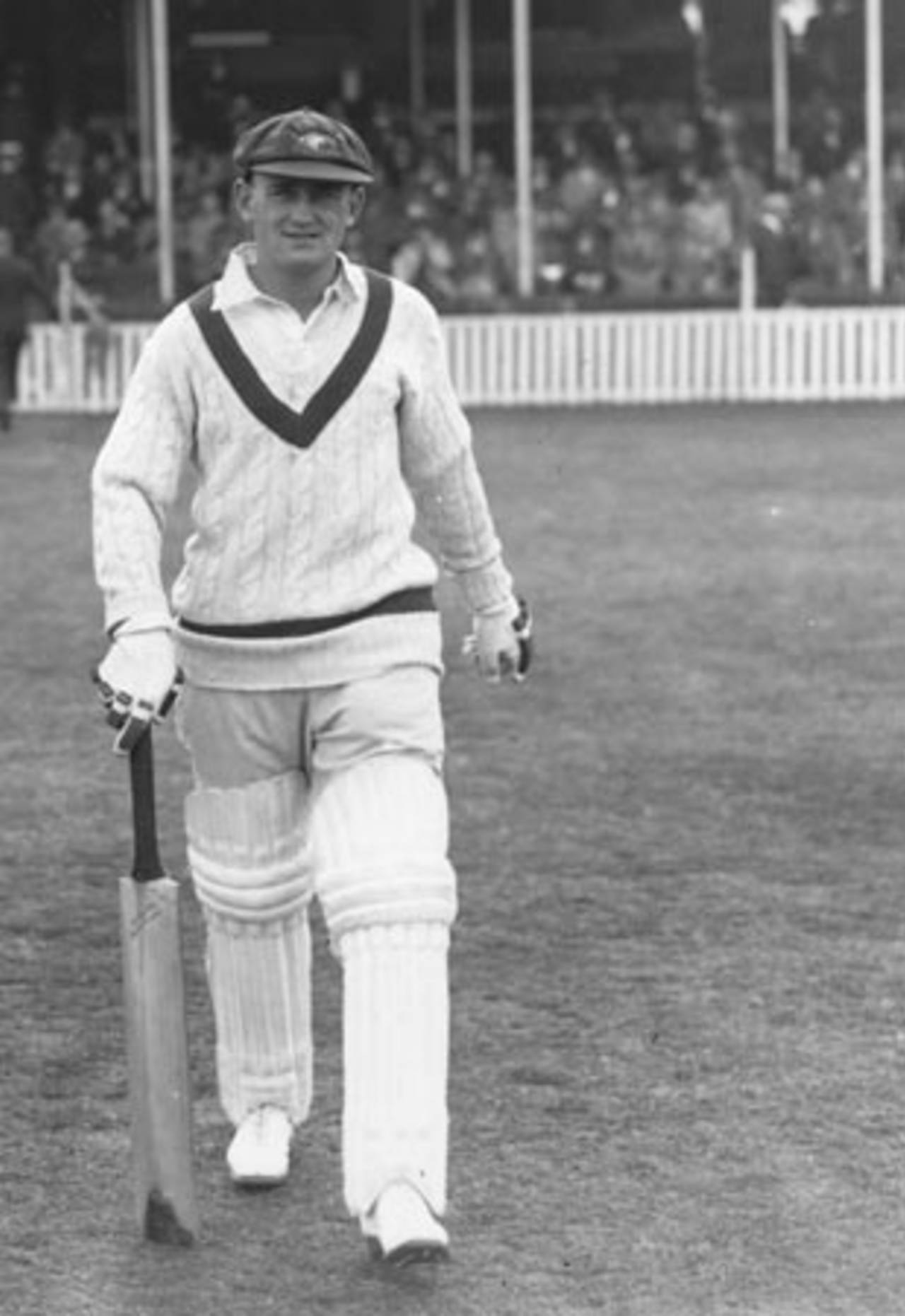

McCabe: someone who, on his day, could create something finer than the best work of the very best • Getty Images

To pore over the scoring wagon wheel of Stan McCabe's 240 against Surrey at The Oval in 1934 is to wish for the invention of time travel. Twenty-nine boundaries, most of them clattered behind the batsman's own capped and nearly hairless head. Fourteen went between square leg and the wicketkeeper: pugnacious, geometrically perfect hook shots. A half-dozen more rolled in a small triangle between first slip and point: cuts and late cuts, caressed with the soft hands of a butterfly house curator. So sweetly did McCabe used to time his cut shots that slip fieldsmen of the day reckoned they made no sound, as if his bat were made of feather not willow.

Pore and wish, and keep poring and wishing, till the elegant and crisscrossing pencil strokes start to blur. And the more you know it's useless: time travel is one fiction science shall never make real. And the less, suddenly, it matters. For they are all there already. Hooks, cuts - all there in our heads.

Two years or so later McCabe was batting with Don Bradman on the fourth afternoon of an Adelaide Test against England. Australia were behind in the series and trailing on first innings. As the partnership swelled, England's grip on the Ashes loosened. McCabe freewheeled to 55. Bowler Robins had a plan. The bait was set: a man on the leg-side fence, a ball pitched short. McCabe, aptly, got hooked. The catch was juggled, then held, and off he skipped.

Afterwards Bradman gave him a talking-to. Son, what the blazes were you thinking?

"Well, Braddles," replied Stan, "if I get that sort of a ball again, I'll play the same shot."

To conclude that Bradman was in the right and McCabe's way the wrong way, it helps if you have a ribbon of steel in your gut and a chicken-wire fence round your imagination.

There are perhaps three kinds of cricket heroes. First, as a child, is the one you idealise and idolise. When an over's completed and the fieldsmen cross ends you look out for his face - is he happy? sad? fretful? - and when he is batting or bowling you gnaw at your wrist until it goes red and scabby. Later, with wisdom, come the ones whose style or attitude or some personal idiosyncrasy you appreciate. If it is his turn at the crease you might cancel lunch or delay going shopping and make sure you are in front of a TV or at the ground. It's something less than love; sort of a kinship.

All the while, and with you all your cricket-watching life, is a third category of hero: the One I Never Saw Play. Stan McCabe, dead 41 years, and born a century ago today, is that person in the minds of thousands.

It has its advantages, being dead and gone. To see a sportsperson play is to be aware of their frailties and to know they are human. Mystique - there's not much of that. But Trumper, Ranji, MacLaren, Jackson… We know them from tales in books, and they have been written about in colours richer than eyes can possibly see. Maybe the giant they have become in our heads never existed. But it is comforting to think that they might have, and to feel like we understand them, we know them. The cold reality that they died before we were born so we could not possibly have known them only adds to the miraculousness of the relationship. The giant grows and grows.

Jerky video and fuzzy black-and-white pictures of McCabe suggest a balding youth with a certain light-footedness, a suppleness of wrist, a twinkle in the eye. And yet: most of the photos are of him coming or going. In the few action shots, we cannot honestly make out his eyes. The writers write that he was flawless against spin bowling - yet flawlesser against pace. He was largely uncoached. He learnt to play on the concrete pitches of Grenfell, a town of many sheep, stepping forward to balls pitched full and back to balls short. His batting, all who knew him agreed, mirrored his personality: a personality not quite human, but something a bit finer than that.

"When the ball sped from his bat it was as though the delight he took in the stroke was tempered by the sympathy he felt for the bowler"Jack McHarg, McCabe's biographer

He never got grizzly with umpires. Never grew cagey in the 90s. Cop a rough decision, which happened sometimes, or get caught on the pickets for 98, which also happened, and still he'd depart with what everyone calls that "little skip" of his. You often hear people use the phrase "Ashes battles". Stan played them like they were games in the local park, except there were more people watching, and the people watching should be kept entertained. Why hook along the ground when hooking through the air was so much more fun? He tended to score few short singles. Runs for the sake of runs; there was no adventure in that.

When the Poms were at their most unctuous and unbearable - the Bodyline summer of 1932-33 - Stan was one Australian who would still chat to them. Years later, opener Arthur Morris asked Stan why he'd never written his memoirs. "I don't hate anyone enough," said Stan.

No hate in the man, no hate in his cricket: McCabe at the crease was the personification of batting with haste yet no hate. Bowlers getting clobbered didn't mind so much if it was McCabe doing the clobbering. Their warmth was reciprocated. Cricket lover Jack McHarg, who saw McCabe bat and in 1987 wrote the McCabe life story that McCabe himself wouldn't write, observed: "When the ball sped from his bat it was as though the delight he took in the stroke was tempered by the sympathy he felt for the bowler."

Something a bit finer than human, that is.

Superhuman is a word commonly ascribed to three epic innings he played. These three knocks, as any frequenter of this website knows, are the three big reasons why McCabe at 100 stands as tall in our imaginations as the boy of the depression years who could charm old gentlemen into tossing their straw hats in the air. All three, as you dwell on the tales behind them, sound impossible. In sober moments, an eerie hunch can creep up on you: maybe McCabe was - is - a work of fiction. What's real? What's imaginary?

His unconquered 187 in Sydney was one of two occasions in all cricket history when you could categorically say that Bradman could not have done it. Bradman went to his grave believing that when Harold Larwood bowled Bodyline at batsmen's skulls on lively pitches, the only way of defeating it was by jumping to leg and slashing through off, twisting your neck out of the firing line and turning your back on the textbook. This ignores the fact that for four tantalising hours McCabe was textbook perfection itself, climbing up on his toes to hook and to cut. He was something close to Hercules that innings. And yet he remained humble young Stan, refusing to look at the next day's newspapers because they'd only contain "a lot of exaggerated praise that it wouldn't do me any good to read".

Reeking no less of fiction is his 189 not out in Johannesburg. There, on a spitting pitch, amid flashes of lightning, the thunder of McCabe's hitting persuaded - most staggering of all staggering twists - the fielding side to appeal against the light. Last of McCabe's three, a stroke-perfect 232 in Nottingham, was the second of two beyond Bradman. This we know because Bradman admitted so himself. "Stan," said Don, "I would give a lot to play an innings like that."

McCabe on the attack during his 187 in Sydney•The Cricketer International

These three innings had plenty in common: grace, excitement, speed, inventiveness, precise placement, nimble feet. And adversity. Not that McCabe considered being behind in a game of cricket to be true adversity. And not that he feared adversity. Adversity made batting feel like fun. Too often in Tests he came in after Bradman and Bill Ponsford. The score would be two for several hundred. His job would be to belt weary opponents around the head. Nightmare job - and one, with a discreetly errant get-out shot, he invariably sidestepped.

Did he even enjoy playing Test matches? Jack Fingleton, his batting partner for three hours in Johannesburg, suspected not. "I really think he hated Test cricket, particularly towards the end of a series… He begrudged the nervous toll a series exacted." It is a wrenching thought, and a question his biographer does not dare ask. But what are we to make of the following set of numbers? In the first three Tests of a series, McCabe was dismissed 34 times for an average of 60; in the last two Tests, he was out 23 times and averaged 29. Then when it was over he'd go back to his three brothers in Grenfell, or wife Edna at Beauty Point, and tell 'em what happened.

Stan McCabe, you might suppose, was the rarest of beings: someone who, on his day, could create something finer than the best work of the very best, but whose day does not come often, maybe only three times in a whole life. "It was strange," noted Bradman in a letter to Jack McHarg, "that a man with such wonderful ability did not produce more than those three special innings."

Wrong again, Braddles. There were many more than three - think of that 240, utterly unremembered by history, against Surrey. Sometimes, if you shut your eyes tightly enough, you can see him standing there still, cutting and hooking.

Christian Ryan is a writer based in Melbourne. He is the author of Golden Boy: Kim Hughes and the Bad Old Days of Australian Cricket