The most underestimated batsman of his era

Derek Randall played the game as we thought we would if we were in his shoes, only with 2000 times more natural ability

Marcus Berkmann

Apr 24, 2011, 2:51 AM

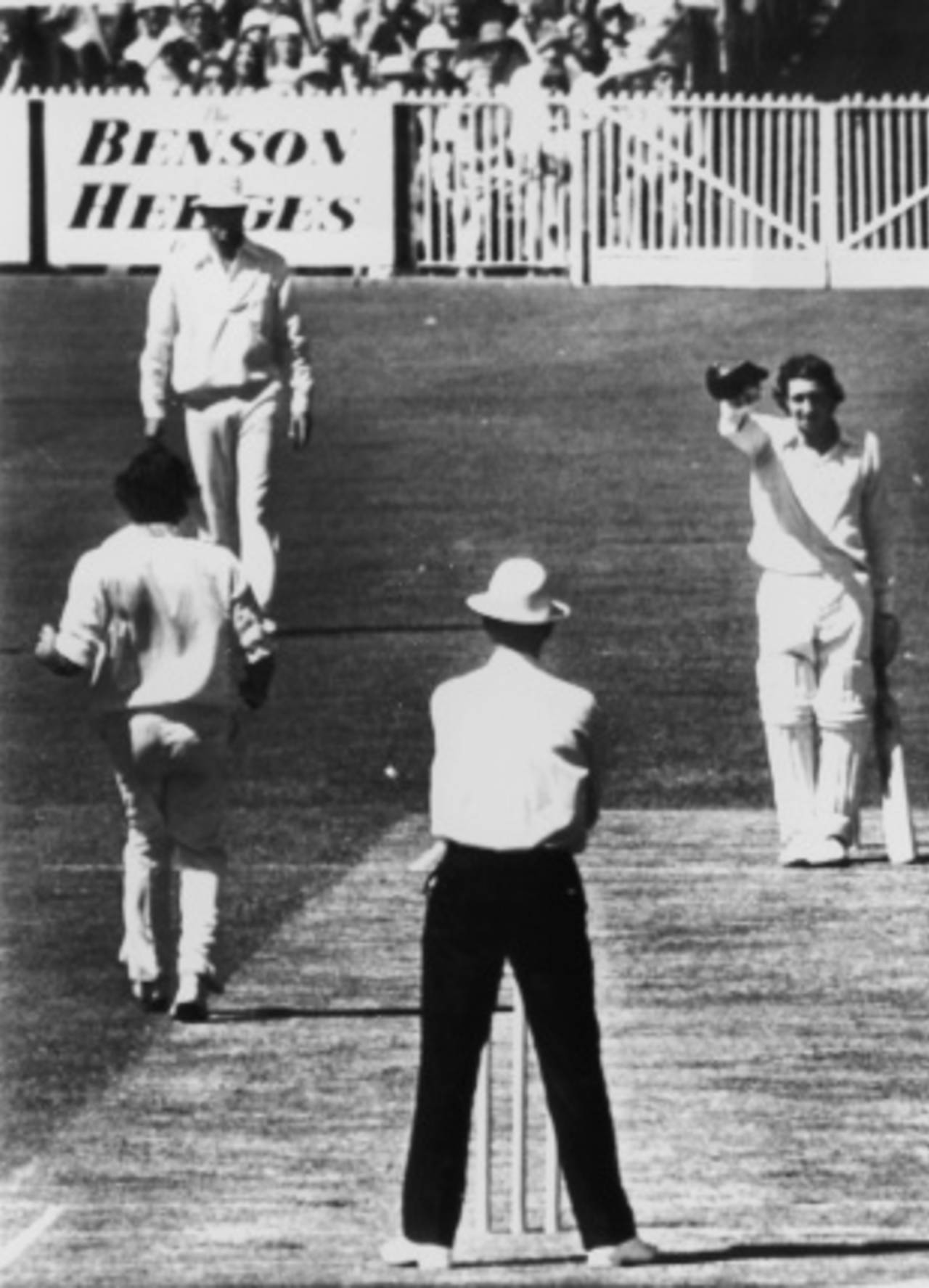

Derek Randall doffs his cap at Dennis Lillee after receiving a bouncer in the Centenary Test • Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Cricket, as we all know, is a team game played by individuals and no cricketer can have been more beguilingly individual than Derek Randall. Modest of stature, equipped with a pixie-ish demeanour, and liable to doff his cap at insane Australian fast bowlers, Randall was a one-off.

Viewed with the dispassionate gaze of hindsight, his figures may not look much: 47 Tests between 1976-77 and 1984, 79 innings, 2470 runs with seven hundreds and 12 fifties, five not-outs, average 33.37.

After Randall was dropped for the last time, the role of "slightly frustrating underachieving England middle-order batsman" was occupied by Allan Lamb, Mike Gatting, Graeme Hick, Mark Ramprakash and John Crawley, each of whom drove me mad at various times in his own way. But Randall, I forgave everything.

Although 47 Tests is not a bad haul for a top-six batsman who did not score a huge number of runs, I felt at the time that he should have played more, and I feel it still. Randall was, for me, the most ill-used and underestimated batsman of his era, allowed fewer chances than his contemporaries, and punished more swiftly for every failure. Writing these words, I feel my teeth start to grind uncontrollably.

He is, of course, best known for the Centenary Test of 1976-77. It was only his fifth Test, but if you are going to score an epic 174 against Australia, this was the Test to do it in. Mere months before Kerry Packer turned the game upside down and inside out, this was a grand celebration of all that had gone before, without the slightest clue of what was to come.

The Queen was there, so were thousands of elderly former cricketers, and Randall produced the performance of the game. England needed 463 runs to win and, astoundingly, came within 46 runs of it. The cap-doffing incident followed a particularly well-directed Dennis Lillee bouncer. There could be no better way to disarm the old growler. Another bouncer was flat-batted to the midwicket boundary "with a speed and power that made many a rheumy eye turn to the master of the stroke, the watching Sir Donald Bradman. Words cannot recapture the joy of that moment." This was Wisden's unusually effusive description. It was my hero's defining innings and, needless to say, I did not see a ball of it.

Later games, though, I remember with unnatural clarity. Randall was always a nervous starter. At times, when he was out of form, he could look as though he had never actually batted before and had just wandered on to the pitch by mistake. We who revered him sat through these occasions in torment, hoping he would somehow survive his first few overs, for when he finally found his touch everything clicked in the most magnificent way.

He had that ability, most recently seen in Kevin Pietersen (who otherwise resembles him in no way at all) to play shots you did not think were possible, and make them look easy. It was an outrageous talent that communicated the sheer joy of batting. For Randall, Test cricket never seemed like just another day at the office. He played the game as we thought we would if we were in his shoes, only with 2000 times more natural ability.

True, his game was not without its technical flaws. Like so many Test batsmen he had a tendency to nibble fatally outside off stump. Apparently the man himself believed that his relatively short reach made him vulnerable to such balls, although his reach never seemed that short when he was swooping on balls in the covers like a hyperactive orangutan.

Low centre of gravity, long arms, astounding instincts: what else do you need? The fielding, of course, was his great additional value to a side. It was said, so often that I probably said it in my sleep, that he was worth an extra 20 runs to his side in the field, although I remember once arguing in the pub that it should be 23, while someone else said 18. Those who did not buy into Randall really did not buy into him. Their number included several England selectors.

But, though constantly shoved up and down the order, Randall had a tendency to score runs when they mattered. I particularly remember a gritty and ground-out 105 at Edgbaston against Pakistan in 1982 when he was opening the batting, mainly because no one else would. In Melbourne he batted at No. 3 but I always thought he looked more comfortable at Nos. 6 or 7, at which positions he averaged in the mid-40s.

My favourite innings of his, better than any of the hundreds, was an 83 at Trent Bridge against New Zealand in 1983. Coming in at 169 for 5, he and Ian Botham flayed the Kiwi bowling to all corners. Botham bludgeoned a century and stole the headlines but it was Randall's batting that delighted the connoisseurs. In one over from Richard Hadlee, a Nottinghamshire team-mate who at the time was taking wickets pretty much when he felt like it, Randall hit three boundaries in three balls through the off side. Each ball was slightly different, each shot was slightly different and the result was the same. It was joyous and sublime.

The next year Randall got 0 and 1 against West Indies and was dropped forever. Typically he had his most productive county season in 1985, when England were trouncing Australia and no middle-order places were available. It was not always a lucky career but it was an honourable and at times brilliant one. Someone put the Centenary Test on DVD, please, and add that Hadlee over if there is room.

Marcus Berkmann is the author of two books on cricket, Rain Men and Zimmer Men. This article was first published in the Wisden Cricketer in 2006. Subscribe here