Who was India's first great batsman?

In part one, a look at three Indian-born batsmen who went on to achieve glory in other countries

Stuart Wark

11-Jul-2013

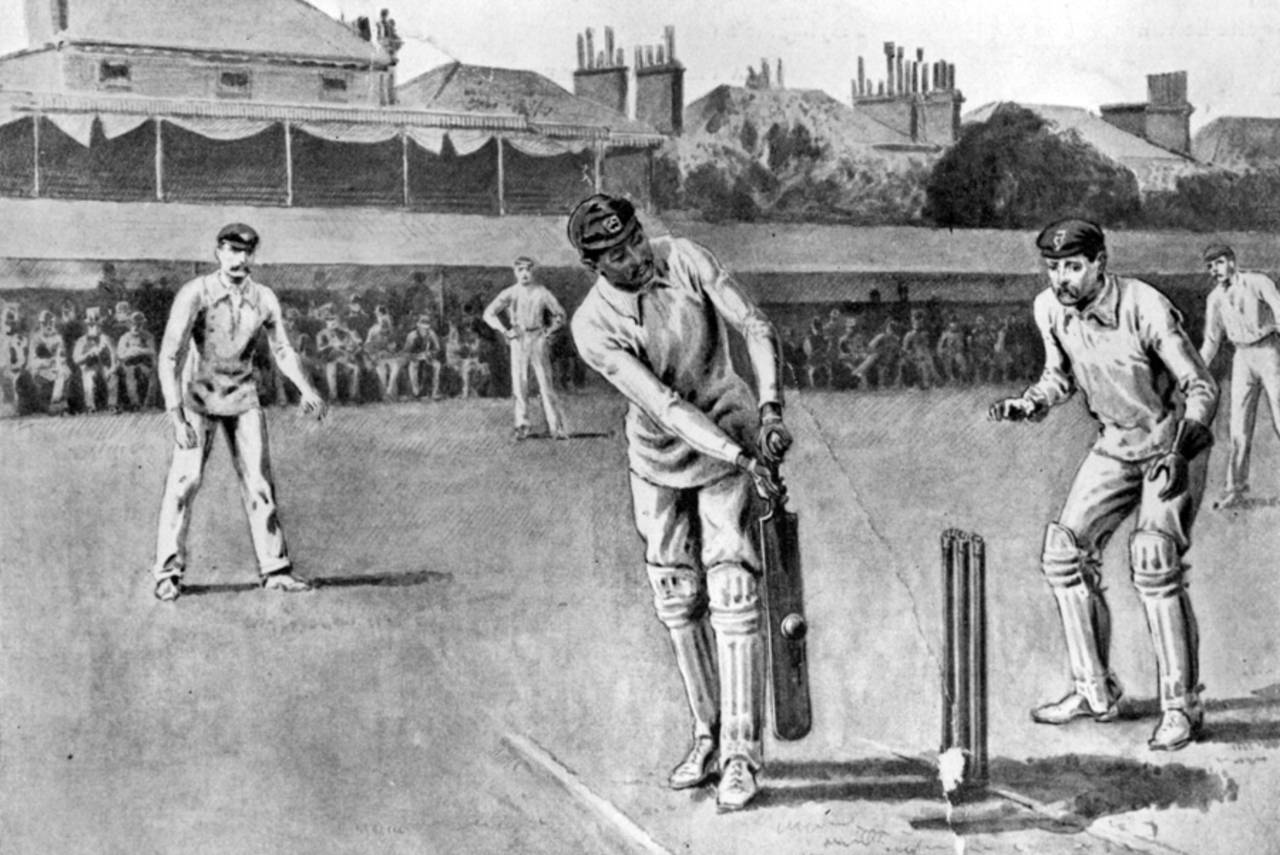

A portrait of Ranjitsinhji playing his favoured leg glance • Getty Images

There are numerous articles and opinion pieces proclaiming the undoubted greatness of Sachin Tendulkar. He has been the heart of the Indian batting order for decades, his place in the pantheon of legends is unquestionable, as is his status as India's greatest batsman in the past 20 years*. However, it is interesting to delve back in history to consider who India's first great batsman was. For the purposes of the argument, an entirely arbitrary decision was made to only include batsmen who played Test cricket.

The first player born in India to play Test cricket was Bransby Cooper. He was born on March 15, 1844 in Dacca in British India, which is now known as Dhaka in Bangladesh. His family moved to England when he was a child, and he played first-class cricket for a number of counties before moving to Australia in 1869 after a brief sojourn in the United States. Cooper was quickly selected for Victoria, and was soon recognised as the leading batsman in colonial cricket. He was duly chosen to play in the first official Test match in Melbourne 1877 which, in a nice coincidence, started on his 33rd birthday. This was to be his only Test match; scores of 15 and 3 were not indicative of his batting prowess. It is hard to make a compelling argument that Cooper was India's first great batsman, as he never played first-class or Test cricket for, or even in, India. Nonetheless, it is worth acknowledging him as the first Indian-born person to play Test cricket.

The next individual who could be considered India's first great batsman was also born in India, but also did not represent them at Test level. This man was KS (Kumar Shri) Ranjitsinhji, known by all supporters of the game simply as Ranji. He was born on September 10, 1872 to a minor nobleman in the Indian province of Kathiawar. However, in a stroke of great fortune for Ranji, Jam Sahib Vibhaji, who was the ruler of the local province, adopted Ranji as his heir. This allowed Ranji the opportunity to attend school in England, and his obvious skills with the bat were shaped by RS Goodchild, who was the headmaster of St Faith's College.

Ranji attended Cambridge University after finishing school, but he was not included in the Cambridge side in 1892. In a sign of racism that would continue to haunt Ranji throughout his cricketing career, FS Jackson, captain of the Cambridge side, later admitted that the fact that Ranji was an Indian had counted against his inclusion. However, Ranji continued to perform with the bat, and was awarded his Blue in the game against Oxford at Lord's in 1893. After leaving Cambridge, Ranji joined Sussex in 1895 and scored 1766 runs at 50.16.

In 1896, Ranji continued his excellent county form, and he was widely viewed as being worthy of a place in the first Test team to play the touring Australians at Lord's. In light of the frequent whinging about selectorial blunders in current times, it is worth reflecting that England did not have a standard set of national selectors in 1896. Instead, it was the right of the county at which the Test was played to determine the players. Lord Harris, the president of the MCC at the time and the former governor of Bombay from 1890 to 1895, was vehemently against the inclusion of Ranji in the English side. He openly referred to Ranji a "bird of passage", arguing that since Ranji had been born India rather than England, he should not be considered. This flew in the face of the fact that England selected players including Billy Murdoch, John Ferris, Sammy Woods and Plum Warner, who were all born outside of England. Also, it is quite ironic to note that Lord Harris was born in the West Indies. Nonetheless, his views held, and Ranji was overlooked for the first Test side.

However, Lord Harris' power was limited to affairs at Lord's, and with the second Test played at Old Trafford, the Lancashire board immediately selected Ranji to make his international debut. With his selection, Ranji became the first person from India to play for England, and followed Cooper as only the second Indian-born Test cricketer. Ranji immediately showed his class, compiling 62 in his first innings, and following it with 154 not out in the second. Only one other English player passed 50, and whilst Australia won the Test, the great Australian allrounder George Giffen described Ranji's innings as the finest he had ever seen. He also added that it should not be surprising as Ranji was the batting wonder of the age.

Interestingly, Ranji was never to play first class-cricket in India. However, he did play club cricket during the 1898 summer. In September and October of 1899, Ranji led a team of English players on a tour of North America, playing two games against the Philadelphians. At this time, the Philadelphian Gentlemen were able to put a team on the field that was competitive against most world sides, and in Bart King they possessed one of the best bowlers in the world. The KS Ranjitsinhji XI won both games by an innings and over 100 runs, with Ranji's contribution in his side's two innings being 68 and 57. In spite of the team winning both games convincingly under his leadership, and his captaincy efforts with Sussex over the years, Ranji was never considered for this role with England. There were enough individuals of Lord Harris' ilk in the various positions of power who ensured that Ranji would never rise to become the first Indian-born player to captain England. That honour would come later to Douglas Jardine.

Ranji was officially installed as the Maharajah Jam Saheb of Nawanagar on March 10, 1907. The responsibilities of ruling restricted Ranji's opportunities to continue playing cricket in England. He played on in a limited capacity in 1908 and 1912, but injuries and illness prevented him completing the seasons in full. In 1915, Ranji suffered a hunting accident in Yorkshire, which resulted in him losing his right eye. He wore a glass eye and spectacles thereafter, but his first-class career was effectively over.

Ranji died in the palace of Jamnagar on April 2, 1933 of heart complications following a dose of pneumonia. His body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered into the Ganges. It is clear that he deserves to be remembered as one of the greatest batsmen of all time. Perhaps Wisden's summary of Ranji remains the best: "If the word genius can be employed in connection with cricket, it surely applies to this Indian batsman." However, it is difficult to argue that he was India's first great batsman. A common criticism of Ranji in modern times is that he did nothing for Indian cricket, and in fact viewed himself as solely an English cricketer. He certainly did not ever play first-class cricket in India, and did push his nephew Duleepsinhji to play for England rather than India. It is difficult now to accurately assess what effect Ranji had upon cricket within his native country. He certainly inspired such Indian greats as CK Nayudu to believe that they were able to compete and excel at cricket as much as any English player.

Ranji's nephew, Kumar Shri Duleepsinhji, is another candidate for the first great Indian batsman. He was born on June 13, 1905 in Kathiawar, which roughly corresponds to what is currently Gujarat state. As with his famous uncle, Duleep went to Cambridge and achieved his Blue there in 1925. He also represented England rather than India at Test level, but he only played 12 Test matches. However, he showed his undoubted class in these dozen games, scoring a total of 995 runs at 58.5. This average stacks up well against anyone in the history of international cricket, and is in front of English contemporaries such as Wally Hammond (58.45), Patsy Hendren (47.63), Frank Woolley (36.07) and Douglas Jardine (48).

Duleep's highest score at Test level occurred in the second Test of the 1930 Ashes series against Australia. He scored 173 in England's first innings, in which only one other player, Maurice Tate, who swung lustily at the end for 54, passed fifty. Unfortunately, Duleep's innings has been largely forgotten with the passage of time, as a certain Donald Bradman responded for Australia with 254 in what he described as his greatest innings. Duleep followed his first-innings century with a polished 48, but Australia went on to win comfortably by seven wickets. However, it was his efforts in a Test match against newcomers New Zealand that really demonstrated Duleep's poise and great technique. On a pitch at Lancaster Park in Christchurch on which neither team passed 200, Duleep top-scored in both innings, with his first innings of 49 being the highest score in the match. His unbeaten 33 then steered England home from a slightly precarious position during a small fourth-innings chase.

Sadly, Duleep struggled throughout his career from ill health, and this limited his first-class and Test career significantly. He died at the very premature age of 54 from a heart attack on December 5, 1959. He was an incredibly popular individual, and it appears that he was not subject to some of the more blatant prejudice that affected Ranji's career. However, as with both Cooper and Ranji, Duleepsinhji did not actually play for India in Test cricket; his first-class career finished in 1932, the year India played their inaugural Test. As such, it would seem appropriate to look further again to determine exactly who was India's first great batsman.

* Arguments about whether Tendulkar is better than Sunil Gavaskar can wait for another day.

Stuart Wark works at the University of New England as a research fellow