'A fine ****ing way to start a series'

Few tours have got off to a more controversial and acrimonious start than the first post-war Ashes series

Martin Williamson

27-Nov-2010

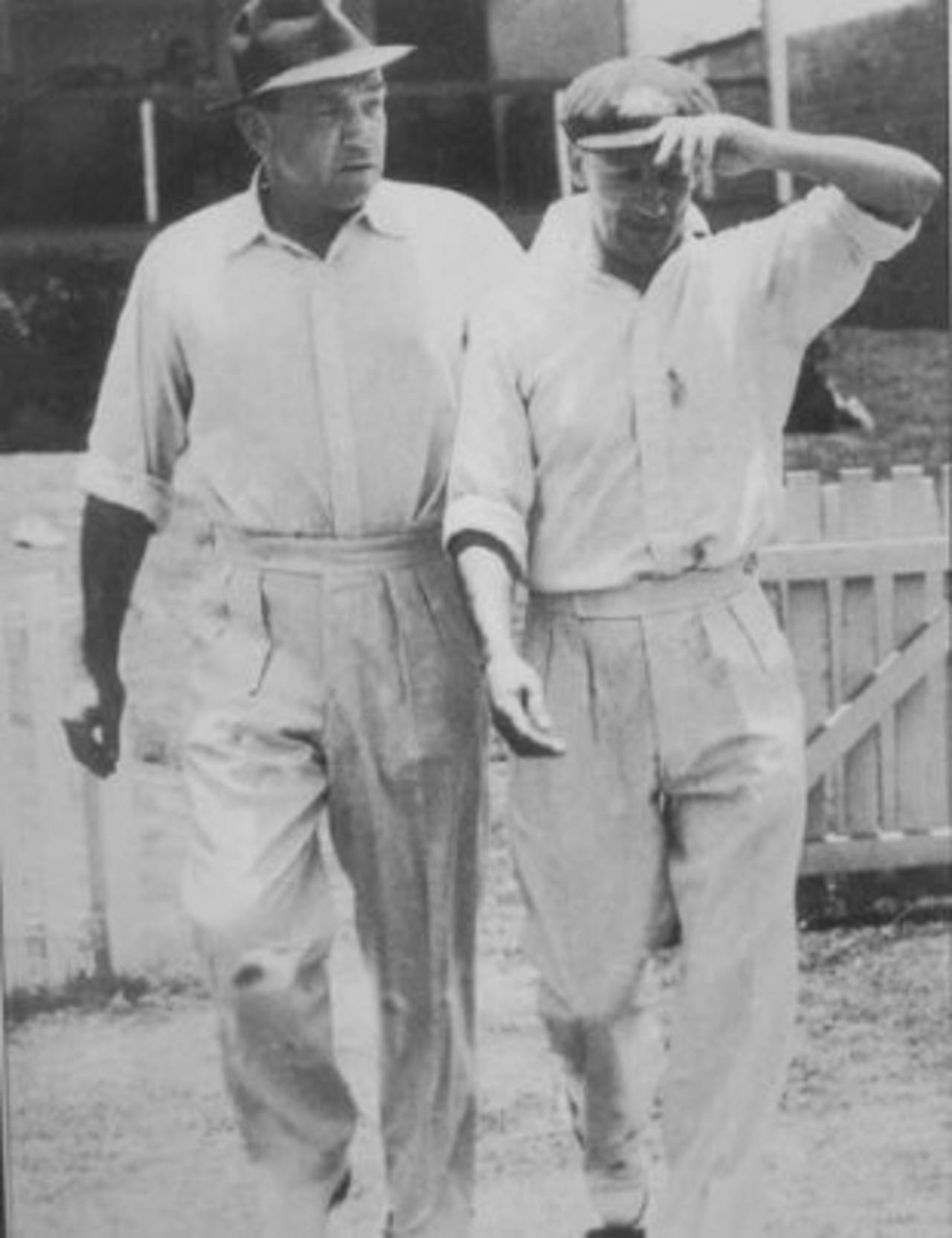

Wally Hammond and Don Bradman walk out to toss at Brisbane. Bradman reportedly threw his hands up in delight when Hammond called incorrectly • ESPNcricinfo Ltd

Ashes series are traditionally hard fought but, with a few exceptions, not overly controversial. Rarely, though, can any series have got off to a worse start than the one that began in Brisbane in November 1946.

When England landed in Australia in October, they were warmly welcomed. It was the first major tour since the end of the war and was a reassuring sign that the world was getting back to normal. And the two countries were due to be led by rivals who had dominated batting in the 1930s - Don Bradman and Wally Hammond.

Hammond had enjoyed a decent summer in 1946, but nonetheless it was all too clear that his powers were on the wane. He was 43, becoming rather portly, and seemed a shadow of the pre-war batsman many believed was the greatest his country had produced. Those closest to him had advised that he should not make himself available to lead a tour many in England believed was far too soon for a country still struggling to overcome the ravages of war.

But Hammond was keen on one more tilt at the old enemy, even though, as former team-mate Bill Bowes noted, "the co-ordination between hand and eye was not what it used to be". However, he was England's pre-war captain and it was inconceivable that the selectors would not ask him to go.

Meanwhile in Australia, Bradman, five years Hammond's junior, was also seemingly in decline. He had been invalided out of the army - remarkably because of poor eyesight - his war record was the subject of private sniping by his detractors, and he was suffering from health troubles. Although he had resumed playing in 1945-46, his participation in the following season's Ashes was the subject of almost daily newspaper speculation and was far from guaranteed.

By the time England set sail, Bradman had just about overcome a shoulder injury, but gastritis had left him a stone lighter, with a pinched look. When Denis Compton, who had played against Australia in 1938, laid eyes on him again he was shocked. He recalled: "Some of us wondered whether or not he was due for a nursing home rather than a cricket pitch."

As the first Test loomed Bradman finally decided to make himself available, albeit against his doctor's advice. As Charles Williams notes in his 1996 biography, Bradman: "It was a courageous decision. He could have rested on the laurels of the 1930s and made himself a great deal of money by writing instead." Perhaps he did not want to bow out in the knowledge that his last appearance had come at The Oval in 1938, where he was unable to bat as Australia lost by an innings and 579 runs.

The pressure on Bradman in Brisbane was immense. He won the toss and batted, but soon found himself at the crease as Australia got off to a shaky start. Nervously and uncharacteristically he took a good two minutes on reaching the middle before he was ready to receive his first ball. He then struggled, and one report said his "survival through the opening minutes was close to miraculous". Covering the tour for the Guardian, Neville Cardus noted: "in the first half-hour he committed more miscalculations and streakiness than memory holds of all one's experience of him".

But he hung in there until, when he had made 28, something happened which Williams said "caused more friction ... than any single incident since Woodfull was hit over the heart by [Harold] Larwood in the Adelaide Test of 1933".

Bill Voce bowled a virtual yorker-length delivery wide outside off stump, which Bradman tried to chop down on, in an attempt to guide it wide of the slips. His contact was not good, and the ball made its way at chest height to Jack Ikin at second slip. So certain were the fielders that they had Bradman that they did not appeal - only when they saw him staring into the distance did they belatedly ask umpire Borwick to make a decision, and he immediately gave Bradman not out.

Opinion was divided. Bradman maintained that he had chopped the ball into the ground, and he had his supporters, although Bill O'Reilly, his former team-mate but certainly not a friend, stated that if it were a bump ball then it needed "an uncanny propulsion seldom seen in cricket". Unsurprisingly, there was less doubt among the England side.

Bradman turns as Ikin takes the "catch", with Norman Yardley at gully looking on•ESPNcricinfo Ltd

Perhaps the best account came from Norman Yardley, England's vice-captain, who was fielding in the gully. "I watched the ball bounce from the turf onto the top edge of the bat and go from there straight into Ikin's hands," he wrote. After Bradman had been given not out, "everyone on our side looked in blank amazement, and Hammond in particular seemed to be wondering what to do next. Bradman still looked down."

Yardley added that the umpires later claimed that they thought the ball had been chopped down into the ground. "A ball chopped at that speed bounces steeply up [...] it does not travel parallel with the ground at chest height."

As for Bradman himself, he said that he was not aware he had given a catch. "I heard an appeal; the umpire indicated not out; so I batted on. Naturally, if I had thought I was out, I should not have stayed there."

Perhaps the most telling account came from Keith Miller, who was making his debut and was next man in. "As Ikin held the ball, I instinctively got out of my seat, grabbed my gloves and picked up my bat, my heart pumping like a runaway motor out of control." He soon realised that Bradman hadn't budged. "The crowd were stunned. I sat down again. The Australian players started discussing the incident. Some agreed with the umpire that the ball had come off the ground. Others said it was a straight and simple catch. The match went on. So did the chatter."

Clif Carey, who was commentating on radio at the time, called it as follows: "The next ball from Voce rises as it goes away and Bradman is out ... caught Ikin bowled Voce 28." He later wrote that he had no doubts and was "astounded" when Bradman stayed put and "was at a complete loss for words".

Out in the middle, after a few moments of incredulity, Voce turned and returned to his mark and the over was completed without any further comment. But as the fielders changed over, Hammond, who a team-mate said was "blazingly angry", was heard to loudly pass comment: "A fine f***ing way to start a series." Some claimed the aside was aimed at Bradman, others that it was directed at the umpires. What is certain is that there was no love lost between Hammond and Bradman, and the remainder of the series passed in ill-concealed frostiness.

At the end of the day, Harold Dale in the Daily Express dryly observed Bradman played two innings on the first day, the "first ended when he had scored 28".

The Ikin incident was a turning point, as Bradman went on to make 187 and Australia won the match by an innings and dominated the rest of the series. England's batting was mediocre and the bowling lacked teeth, and it is unlikely that the outcome would have been affected had Bradman been given out at Brisbane … but it might have marked the end of The Don.

He was unwell - he suffered a bad thigh strain and more stomach trouble during the second Test - and was also under considerable pressure. A high-profile failure after an unconvincing stay at the wicket might have been enough to persuade him to call time to avoid his reputation being sullied. As it was, he went from strength to strength, and 18 months later led the triumphant Invincibles tour of England.

There was no such Indian summer for Hammond, and even though publicly he played down the incident - "I thought it was a catch but I may have been wrong" - privately he seethed. The pressure of the tour weighed heavily on him, and he became increasingly remote, even from his team-mates, travelling between matches by car while everyone else took the train. He was also in increasing pain from fibrositis, so much so that he was taking painkillers constantly, even when at the crease, and missed the final Test because of it. And his golden touch with the bat was fast disappearing. It was a sad end for one of the game's greats.

What happened next?

- For Hammond his career was over, bar one ill-advised comeback to help Gloucestershire with fund-raising in 1951

- Bradman cemented his place in history on the 1948 England tour - including a duck in his final innings - retiring with a Test average of 99.94. A knighthood soon followed

- In 1948, Bradman crossed swords with Ikin once again. The scene was more low-key, Ikin's benefit match for Lancashire against the tourists at Old Trafford. With Ikin on 90, Bradman took the new ball. Keith Miller, a war veteran and a man at odds with Bradman's play-to-win approach, looked aghast and threw it back to his captain, saying: "Didn't you know he was a Rat of Tobruk!" It was a temporary reprieve. Ikin was bowled soon after by Ray Lindwall for 99

Is there an incident from the past you would like to know more about? E-mail us with your comments and suggestions.

Bibliography

Wally Hammond - The Reasons Why David Foot (Robson, 1996)

Bradman Charles Williams (Little Brown & Co, 1996)

Australian Cricket Anecdotes Gideon Haigh (OUP, 1996)

Cricket Controversy Clif Cary (1950)

Wally Hammond - The Reasons Why David Foot (Robson, 1996)

Bradman Charles Williams (Little Brown & Co, 1996)

Australian Cricket Anecdotes Gideon Haigh (OUP, 1996)

Cricket Controversy Clif Cary (1950)

Martin Williamson is executive editor of Cricinfo and managing editor of ESPN Digital Media in Europe, the Middle East and Africa