A decade of covering Sachin

Charting the highs and lows, the changing roles and the changing game of the Indian legend since century No. 25

Dileep Premachandran

20-Dec-2010

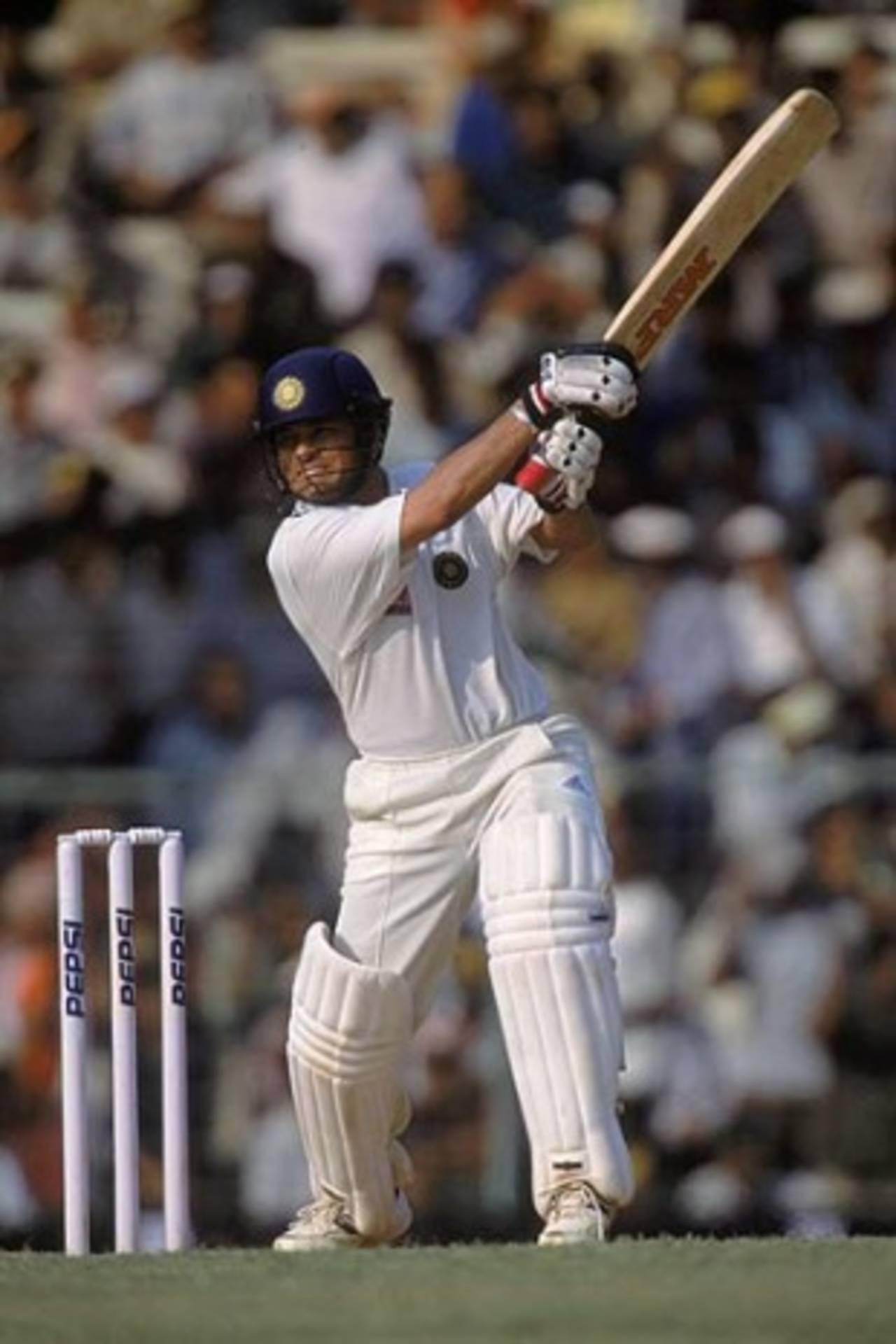

Sachin Tendulkar was sublime against Australia in Chennai 2001, making his 25th Test century • Getty Images

The first hundred that I watched Sachin Tendulkar make was his 25th, at a venue that will always have a special place in his affections. It was March 2001, and VVS Laxman and Rahul Dravid had just ruined everything. Whichever benchmarks are used, that Test match at the Eden Gardens will always belong in the top five whenever the greatest games played are mentioned. It was my first Test match and I left Kolkata suddenly aware that it would only be downhill from there on. The chances of covering such a match again? As likely as a Chris Martin hundred.

In Chennai on the eve of the decisive third Test, I was watching Tendulkar in the nets with Peter Roebuck alongside me. A lot of people there were trying to guess Tendulkar's state of mind. He had been magnificent in Mumbai, the Lone Ranger as India were outclassed in three days. Then, in the greatest match that India had ever played, his primary contribution was three wickets on the final evening. With the bat, he had contributed just 10 and 10.

As we watched him play ball after ball in the nets, Roebuck told me: "He'll score a hundred here. I'm certain of it." That prophecy couldn't be tested on the first two days, dominated by a Matthew Hayden double and the Australian collapse that was to ultimately cost them the series.

Tendulkar was in the middle to face the second ball of the third day after Glenn McGrath had trapped Shiv Sundar Das in front with the first. I don't recall each of the 15 fours or two sixes that he hit that day, but as ever it was the contest with Shane Warne that had everyone on seat-edge. There was one over in the afternoon, with Tendulkar and Dravid having drawn the sting out of the attack.

Warne was bowling round the wicket, targeting the rough in an effort to keep the runs down. Tendulkar backed away from the stumps and just bunted the ball over the slip cordon. Warne tried again. Same result. By the time Tendulkar did it a third time, he had been reduced to swearing in frustration.

The next time the two teams met in Australia, Warne was serving a suspension and confined to the commentary box. Tendulkar's fortunes had also dipped. In his previous seven Tests, including the first three of that tour, he had eked out 253 runs at less than 20. The Guardian commissioned me to do a story on the slump, asking me to talk to another batting great on the subject.

The obvious choice was Greg Chappell, then doing commentary, who had gone through a similar dip in 1981-82. "I don't think there's much wrong with his technique," he said. "The thing with slumps is that it takes just an innings or two to put doubts in your mind. And when you're tense, your reactions tend to be that touch slower than if you are relaxed."

As I was walking back to the press box, Chappell added: "There were signs here that he's getting it back [he had made 44 in the second innings]. Don't be surprised if he scores a big one in Sydney."

Sydney was where he had first unveiled his talent for an Australian audience 12 years earlier. Yet, the innings he played in January 2004 was a completely different beast. Reams have been written of how he hardly hit a ball into the off side through the innings. But for me, it was notable for how he grew into a different role. Laxman, in the form of his life, played an innings touched with magic. Tendulkar's 241 was workmanlike in comparison. After years of carrying the team, he now had a superbly talented support cast around him. It no longer mattered if he didn't set the tone.

By the time he got to Delhi in December 2005, having been level on 34 hundreds with Sunil Gavaskar for nearly a year, expectations had changed. Those watching still expected the moon each time he walked out, but the days of "Tendulkar out, all out" were long gone.

The middle of the decade was a tough time, with tennis elbow and a shoulder problem restricting movement and affecting confidence. At the Kotla, against Murali bowling as well as he ever did in India, there were glimpses of the Tendulkar of old, but by and large the dominator had given way to a man astute at assessing percentages.

Even then, the failures mounted. At Mumbai in March 2006, there were boos when he was dismissed on the final day, and up in the press box, an England international who had once played against him called him a "walking wicket". The consensus was that the glory days were gone. After all, even Gavaskar and Richards had only lasted 16 years at the top.

There were signs of revival in 2007 in England, but the rehabilitation was complete only on his favourite tour. He had never left Australia without a hundred, and in Sydney, in a Test now sadly remembered for the wrong reasons, he rolled back the years with a magnificent innings. He followed that with another in Adelaide, finishing the series with nearly 500 runs.

As much as the runs though, it was the way he was received that meant so much to him. At every venue, the ovation that he got when he walked out was spellbinding. It was common to meet fans who wanted to see India thrashed, and Tendulkar doing well.

Just as Picasso went from his Blue period to Cubism to Surrealism, so Tendulkar has tweaked his game to accommodate both physical changes and the demands of an evolving game

It was much the same at Centurion over the last two days. There was no question of mixed allegiances but the moment Tendulkar walked out, even the most vocal South African fans stood up to applaud. Some, like Dale Steyn, were small kids when Tendulkar first toured. That he was still around when they brought their own young families to the cricket almost defied belief.

At Chennai two years ago, when he scored what he says was his favourite hundred, Kevin Pietersen dramatically described him as Superman. Nearly a decade earlier, some in the stands had wept as one of his finest centuries had been unable to take India over the line against Pakistan. The tears I saw in 2008 were different, happy homage to a man who has been deified in his own lifetime.

What does it feel like to watch him, a decade on from No. 25? In terms of longevity, you can perhaps compare him to Pablo Picasso, another prodigy who never believed in resting on his laurels. And just as Picasso went from his Blue period to Cubism to Surrealism, so Tendulkar has tweaked his game to accommodate both physical changes and the demands of an evolving game.

The technique was always exceptional - how many 18-year-olds could have coped with the pace and bounce that the WACA offered in 1992? - but in recent times it appears more watertight than ever. The full repertoire of shots remains, but the frills are avoided. Like the rich man who knows the value of each penny, he simply refuses to ease up.

Such tunnel vision doesn't sit easy with everyone. "I'd rather watch Graeme Swann bat," said a friend a couple of days back. "Tendulkar's become bloodless and clinical," said another. But just as the praise often leaves him embarrassed and lost for words, so the criticism washes off him. After 21 years, which have encompassed a slump that might have ended other careers, he knows his game better than any outsider. And just like the battered old bat that has been such a trusty aide for the last two years and more, you sense that there are a few more shots to play.

Dileep Premachandran is an associate editor at Cricinfo