Krom Hendricks is an almost unknown figure in cricket history. Born more than 140 years ago in South Africa to a Dutch father and St Helenan mother, he never played a first-class match, and until now, did not even warrant a player page on ESPNcricinfo. But in 1892 he was at the heart of a row that had long-standing ramifications which were to cast a shadow over South African cricket for almost a century.

Hendricks' nickname Krom - his real name was Armien - came from Dutch or Afrikaans for "bent" or "crooked". Almost nothing is known of his life until the time he was selected to play for a Malay XVIII against the touring MCC side led by Walter Read at Newlands on March 22 and 23. Although Read's side won comfortably, Hendricks made the headlines for some excellent fast bowling and finished with figures of 4 for 50.

Read told the local administrators: "If you send a team [to England], send Hendricks; he will be a drawcard and is to my mind the Spofforth of South Africa."

George Hearne, who also played in the game, later wrote: "[He] was very fast indeed. The wicket was very bad and we didn't like facing the man at all. I was captain during the match and everyone began to ask me to let somebody else go in his place … the balls flew over our heads in all directions."

Even on his debut, however, Hendricks was embroiled in controversy. The Malay side was made up of Muslims from Cape Town but Hendricks was at pains to point out he was a Christian.

Two years later, South Africa's provinces were asked to send nominations for the 1894 tour of England, and Hendricks was included in the Transvaal and Western Province selections. However, Hendricks' cricketing claims were ignored. All that mattered was his colour.

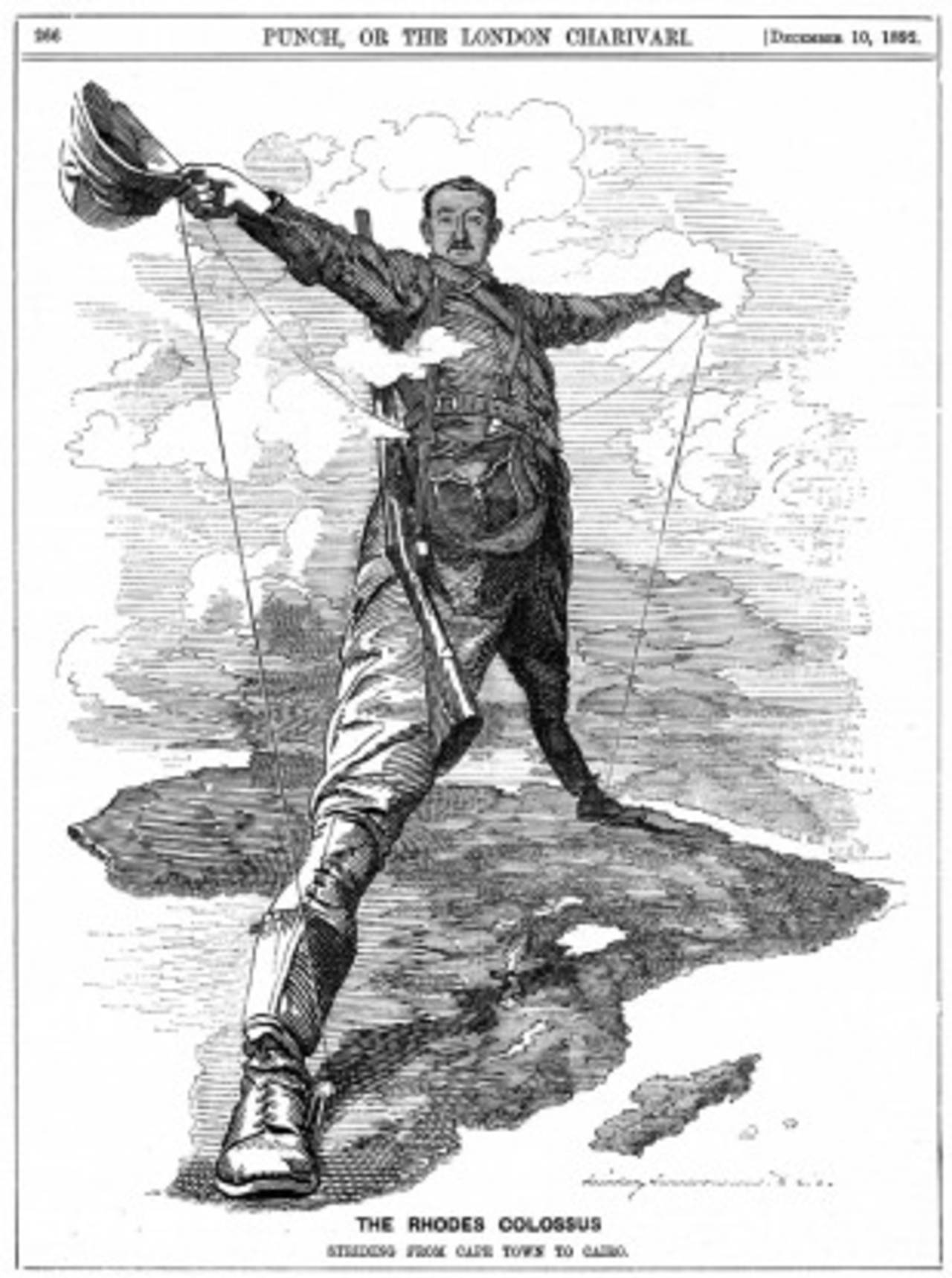

The selection committee chairman was William Milton, an all-round sportsman who had played rugby for England before emigrating to South Africa as a 24-year-old, and subsequently became his adopted country's cricket captain in 1888-89. Milton was also a close associate of the Cape premier Cecil Rhodes, whom he consulted over the matter before vetoing Hendricks' inclusion, arguing it would be "impolitic to include him in the team".

In 1895, Pelham Warner sat next to Rhodes at a dinner where the subject of South Africa's tour came up. "They wanted me to send a black fellow called Hendricks to England," Rhodes told him. Warner replied that he had heard he was a good bowler. "Yes, but I would not have it," Rhodes countered. "They would have expected him to throw boomerangs during the luncheon interval."

There were those who supported Hendricks. Harry Cadwallader, a cricket administrator and journalist who had been picked to manage the tour, wrote to the press with a compromise under which Hendricks would travel in an official role of baggage master, albeit one who played. That idea was dismissed by Hendricks himself. "I would not think of going in that capacity," he told the Cape Times.

Milton was angered by Cadwallader's act and removed him as tour manager for the crime of "placing the Western Province Cricket Union in a very embarrassing situation". Cadwallader still went to England as a journalist and did not hold back from regular digs at the selectors as the tour proved eminently forgettable.

Milton's views were not out of kilter with the general (white) public, and the press railed at the suggestion the side might rely on the skill of a non-white player for success. The Star commented that if the side were to lose, then they "should at least take a licking like white men". Some went even further, citing the example of Hendricks as proof of the need for greater racial segregation within the game, something that was fast becoming an accepted norm.

Bernard Tancred, who had played in South Africa's first two Tests, in 1888-89, argued that Hendricks was showing impudence by even suggesting he was fit to play for South Africa alongside white cricketers. "If he were to go on the same footing as the others, then I would not have him at any price," he said. "To take him as an equal would, from a South African point of view, be impolite, not to say intolerable."

"Sport was inextricably tied to racist ideologies and policies," wrote Jonty Winch in his book 'There Were a Fine Manly Lot of Fellows': Cricket, Rugby and Rhodesian Society during William Milton's Administration. "Milton linked with Rhodes to block the selection of Hendricks… the campaign against Hendricks continued for a number of years, with Milton using his position to dismiss opportunities being secured for the cricketer."

And so the barring of Hendricks continued, with Milton pulling the strings behind the scenes. Hendricks still played, with success, in Cape Town, and later in 1894 it was reported he would be included in the Colonial Born side to play its annual match against Mother Country. Again Milton intervened to scupper the plan, although this time his action found more criticism in the local press.

If he were to go on the same footing as the others, then I would not have him at any price... to take him as an equal would, from a South African point of view, be impolite, not to say intolerable.

South Africa opener Bernard Tancred on the possibility of Hendricks being included in the tour party

In March 1896, Hendricks was named by Transvaal for inclusion in the side for the second Test against Lord Hawke's XI in Johannesburg. Even though South Africa's captain, Ernest Halliwell, who had ironically succeeded Milton in the post, backed the move, there was once more enough opposition to ensure Hendricks did not play.

But by this time the general tide was also turning, fuelled by hostility in the Cape Town press. In 1897, Hendricks was barred from playing for Woodstock in the local league on the grounds he was a professional coach. His club, probably rightly, argued in vain the real reason was because Hendricks was both good and not white.

Thereafter Hendricks disappeared and no more is known about him. The grudging tolerance of non-white players gave way to the increasing segregation that was to blight the game in South Africa for the best part of a century. The game in which Hendricks first came to prominence in 1892 was the only time a touring side played a non-white team until the end of the apartheid era.

What the sad episode did show was that contrary to popular belief it was the British establishment, which governed much of Southern Africa at that time, that was at the heart of erecting barriers between the races, even if it was the Afrikaaners, at that time not part of the cricket fraternity, who subsequently built upon them.

While the game was the preserve of the white elite, the issue of coloured and black players did not arise. It was the emergence of Hendricks and others that caused the establishment to close ranks on racial grounds, with Milton leading the way in the switch from integration to segregation.

"The influence that he wielded was considerable and he, more than anyone, was responsible for preparing the foundations of segregated sport," Winch concluded. It is notable that Hendrik Verwoerd, widely regarded as the "architect of apartheid" was one of the early pupils at a school named after Milton in Rhodesia.

Is there an incident from the past you would like to know more about? Email us with your comments and suggestions. Bibliography

Lord's 1787-1945 - Pelham Warner (Harrap & Co, 1946)

'There Were a Fine Manly Lot of Fellows': Cricket, Rugby and Rhodesian Society during William Milton's Administration - Jonty Winch (Sport in History)

Martin Williamson is executive editor of ESPNcricinfo and managing editor of ESPN Digital Media in Europe, the Middle East and Africa