A flawed character in a flawed system

The cricket book of the season brings many regrets about the rancour surrounding an incredible talent

David Hopps

Oct 10, 2014, 10:36 PM

Sphere

There have been outspoken autobiographies in English cricket before. A generation ago, Geoffrey Boycott outlined the wrongs he felt he had suffered at the hands of Yorkshire and England. Even further back, in 1960, a few tart paragraphs from Jim Laker - scandalous for their time - caused his MCC honorary membership to be rescinded and instead brought him Life Membership of the Awkward Squad.

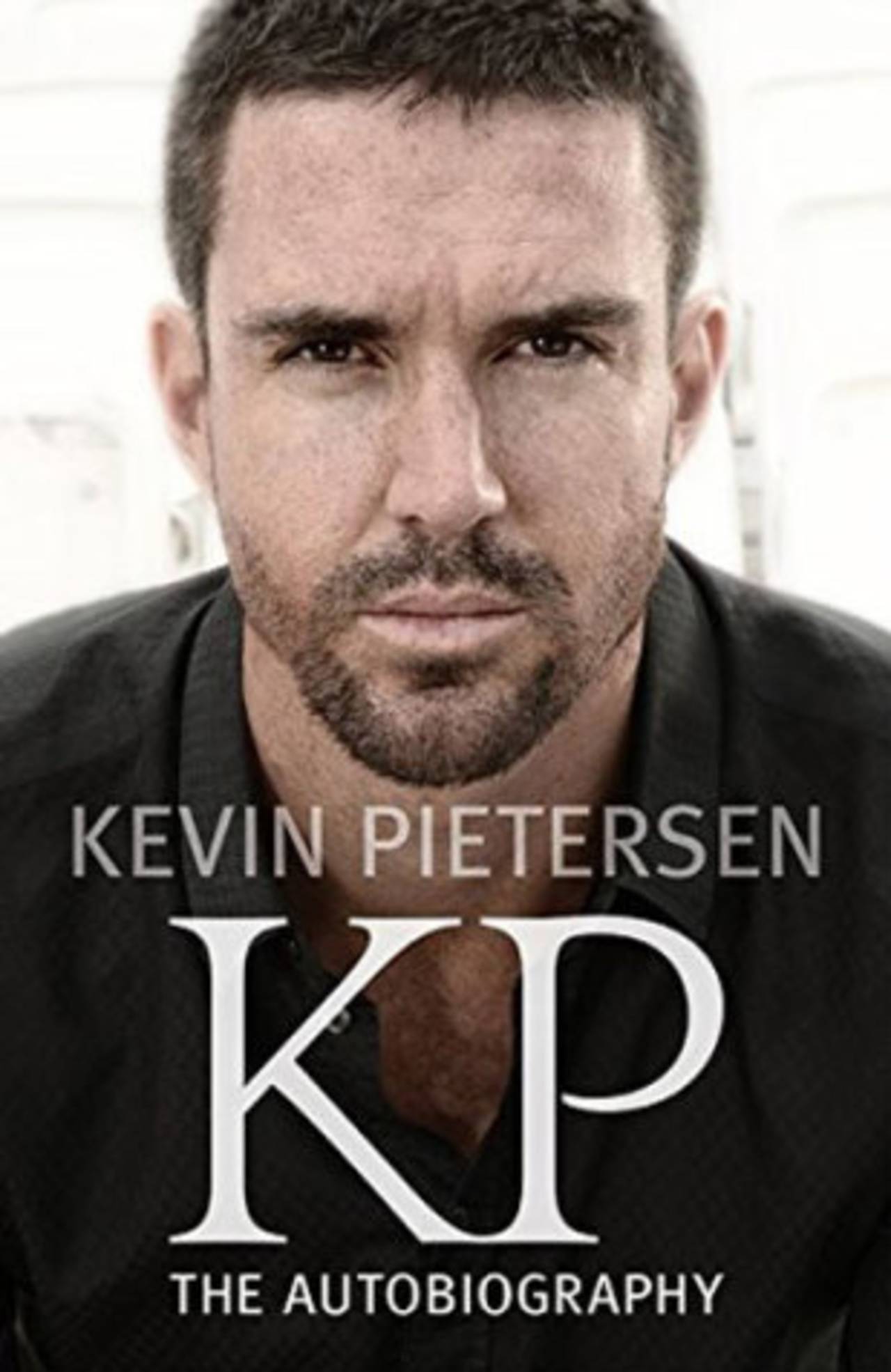

KP: The Autobiography takes the grievances and the settling of scores to a new level. Like it or loath it, it is a book of considerable significance, the aggrieved story of the most maverick, bloody-minded, exciting and ultimately tragic England player of his generation.

Even as publication day arrived, such had been the publicity generated that battle lines were already deeply entrenched, countless words written. KP: The Autobiography is not destined to change minds. It will be dismissed as self-obsessed bleating by his critics, presented as a courageous attack on cricketing conservatism by those who cherish the entertainment he has given them. This will be before most people have read it.

Is it the truth? As somebody remarked perspicaciously, "It is the truth as Kevin sees it." Nobody should question that. But it is a truth seen through a distorted lens.

Pietersen v the World (because that is how it reads, with suitable apologies to wife, child and Piers Morgan) is variously Man v Machine, Rebel v Conformist, Agitator v Compromiser, Freedom v Responsibility, Individual v Team, Instinct v Planning, Attack v Defence, Difference v Normality, New v Old , Sensitivity v Machismo (and what sensitivity!), Emotion v Logic, Perception v Judgement. Sometimes it is also about Right v Wrong, but mostly it is about English cricket's failure to control - and, yes, often to understand - the most individualistic, egotistical, inspirational, crowd-pleasing cricketer of his generation.

Whether Pietersen realises it or not, it is also about a failed relationship. Virtually every breakdown in Pietersen's career can be traced back to a disastrous and debilitating character clash with Andy Flower, known to most as the former England coach, now routinely referred to by Pietersen as the Mood Hoover. Flower, in Pietersen's terms is "contagiously sour, infectiously dour". Flower has rarely allowed himself to comment upon Pietersen, but if he felt inclined to retaliate there is reason to think that "supremely talented, self-obsessed brat" would not be far from the mark.

In his drive for marginal gains, Flower once encouraged psychometric testing of England's players and one of the discoveries was that Pietersen was an introvert; Flower did not need a psychometric test to know that about himself. But that is where their similarities surely ended. Flower is conventional, diligent, precise and rigid; Flower likes to plan and gives praise sparingly; Flower is a private man of great integrity who keeps his relationships on an even keel. Pietersen is the opposite. Pietersen is intensely emotional, lives for the moment, craves praise and dislikes criticism. By his own admission, he has no time for planning - he stares out of the window at team meetings and views coaches as largely redundant.

This aversion to critical thinking was so pronounced that he tells how he routinely avoided breakfast with Moores and Flower in case they deflated his mood. Moores' attempt to bring him into the fold by promoting him as captain after the departure of Michael Vaughan therefore failed almost as soon as it began. Batting liberates him and to capture that perfect state of mind he seeks truth in psychology and something called The Chimp Paradox, which basically tells him how talented he is. Pietersen and England's coaches never build a trusting relationship. Flower, it appears, quickly dislikes him.

When KP: The Autobiography does not push you into taking sides, it leads you into a contemplation of a flawed character. It is forthright, populist and written in such an agitated, self-justifying manner that even the brashest paragraphs cannot disguise the loneliness of the sporting maverick. There is an "I" in team he asserts, reminding us that cricket is an individual game in a team setting. And so there is. But there is a limit. He forever smacks of an individual refusing to accept the strictures of a team sport.

It is forthright, populist and written in such an agitated, self-justifying manner that even the brashest paragraphs cannot disguise the loneliness of the sporting maverick

Many will read all this and wonder how this madness was ever allowed to happen. It is as if those in authority repeatedly sense a virus in their midst only for their clunky anti-virus programs to warn that if they quarantine him several major programs will not function so effectively. Pietersen's very presence repeatedly lays bare the problems of a conservative, fastidious and unwieldy hierarchy in handling the assertive individualism more prevalent in the modern game. The moment England start losing, and Pietersen's form dips, they get shot of him.

Right from the outset, Pietersen identifies with Fred The Soldier, who "follows a different drummer". He says: "I don't set out to go against the flow… but I won't sit down and be told to bat this way or train this way without asking why." This assertion of self, often blind to the team ethic, does not go down well. Everybody who has raised a family can remember the "why?" phase. The first claim to individual freedom comes at two years old. Pietersen has it in abundance.

Some of his explanations of his behaviour are more convincing than others. His version of his fallout with Moores, a coach he found to be a "human triple espresso - so intense" is instructional. He insists that he never gave the England and Wales Cricket Board a Him Or Me ultimatum, just told them that his philosophy was so different from Moores that they could not work together. The ECB, fearing player power, sacked them both. It is a decision that smacks of convenience.

When Pietersen is not demeaning Flower, he is warring with the ECB, forever suspecting - often with good reason - a "world full of little agendas". When Andrew Strauss, who replaces him as captain, proves to be at ease in mollifying such a world, he thinks less of him because of it, suggesting that he is "playing the long game". His unabashed belief in the IPL is another fault line - he loves it, so English cricket does not love him. Here, more than anywhere, he is a victim of his time. As cricket changes, coming generations will see him, on the IPL at least, as unfairly brandished.

But he is not the only victim. Pietersen, who likes to play cricket in a happy frame of mind, sparked a debate in the days leading up to publication by complaining of a bullying culture in the England dressing room. His criticism struck a chord. But there have been few nastier pages in cricket literature than his own destruction of Matt Prior, a sequence where his ghost writer is allowed to go for the jugular - a task he accomplishes with considerable skill - without on the face of it too much justification.

As for fake Twitter accounts and Textgate, why the coaching staff did not bang heads together and sort both in 24 hours is a question that lingers. In English cricket, authority is too often invested in those away from the action. England players' involvement in KP Genius displays a crass failure to recognise that with his ego came sensitivity. For Pietersen's exchange of texts with friends in the South Africa side criticising his captain, Strauss, to be magnified into traitorous behaviour still seems to be an overreaction. The world has heard too much about both subjects. This book adds too many pages to the nonsense and it will be a reader with a healthy sense of perspective who skips the lot of them.

But it's batting that Pietersen is about - even if, reading this autobiography, it is easy to forget. Only when Pietersen gets a bat in his hand, is he truly liberated. "I'm a risk taker by nature," he says in response to those such as the Sacking Judge Paul Downton, who deemed him reckless, not accepting that without the risk he is vastly diminished.

Off the field, he is forever insecure; he jars with those he must live with in close proximity for 250 days a year. He can say he loves someone one day, hate them the next, and both responses feel equally true. He is a South African in England, a star player who needs his ego perpetually feeding, but who is not just excluded from the dressing-room clique but is mocked by it. When he asks for a break to see his wife and family, it is routinely refused. Others get their breaks: it is that IPL punishment thing again. Even his injuries - serious injuries - are disparaged by Flower. A fair and honest man, Flower's disenchantment with Pietersen begins to demean him.

KP: The Autobiography has briefly descended English cricket into chaos. It has no humour, only fleeting references to camaraderie, no praise for the talents of his team-mates, and precious little cricket analysis. But it is a legitimate work of propaganda (so much propaganda has been thrown in his direction, he had little choice but to reply in kind). For those of us not wedded to one side or the other, it leaves an immense sadness that so wonderful a talent has repeatedly exasperated, vexed and been disparaged and excluded.

Why did it have to be this way? Why was England's man management so unsuccessful? As those in charge of England cricket congratulate themselves on the prospect of simpler times ahead, they need to reflect on that question.

England cricket is hurting because of the arguments surrounding Pietersen: arguments that are often Machiavellian in high places, often rabid on social media, ultimately unbearable in the dressing room. But the chaos in England cricket will be transient. New heroes will come and one hopes the public will eventually learn to love the game in records numbers again. Disillusionment is evident and widespread. As Pietersen remarks, you cannot promote a game for the people without communicating with and respecting the people.

Saddest of all perhaps is Pietersen's imaginings that, even after a book as uncompromising as this, he might somehow play again for England. His naïve failure to understand that his challenge to the system has been so extreme that it will never be tolerated symbolises how gauche his self-obsession can make him. It's over and it was quite a ride.

But at a time when so many cricket autobiographies are cravenly dull, when player interviews are delivered as if by rote, and the governing body forever asserts its right to rule in near-secrecy, Pietersen's flawed and overwrought cri de coeur is a book that was better written. Somehow, in this imperfect, suspicious world, he summoned some of the finest innings in England history. We should all be grateful for that.

KP: The Autobiography

By Kevin Pietersen

Sphere

324 pages, £20

By Kevin Pietersen

Sphere

324 pages, £20

David Hopps is the UK editor of ESPNcricinfo