My life in cricket: a six-decade journey

How one fan's life has been transformed from the days of reading day-old newspapers and watching Sobers and Chandra from the cheap seats

Anantha Narayanan

09-May-2020

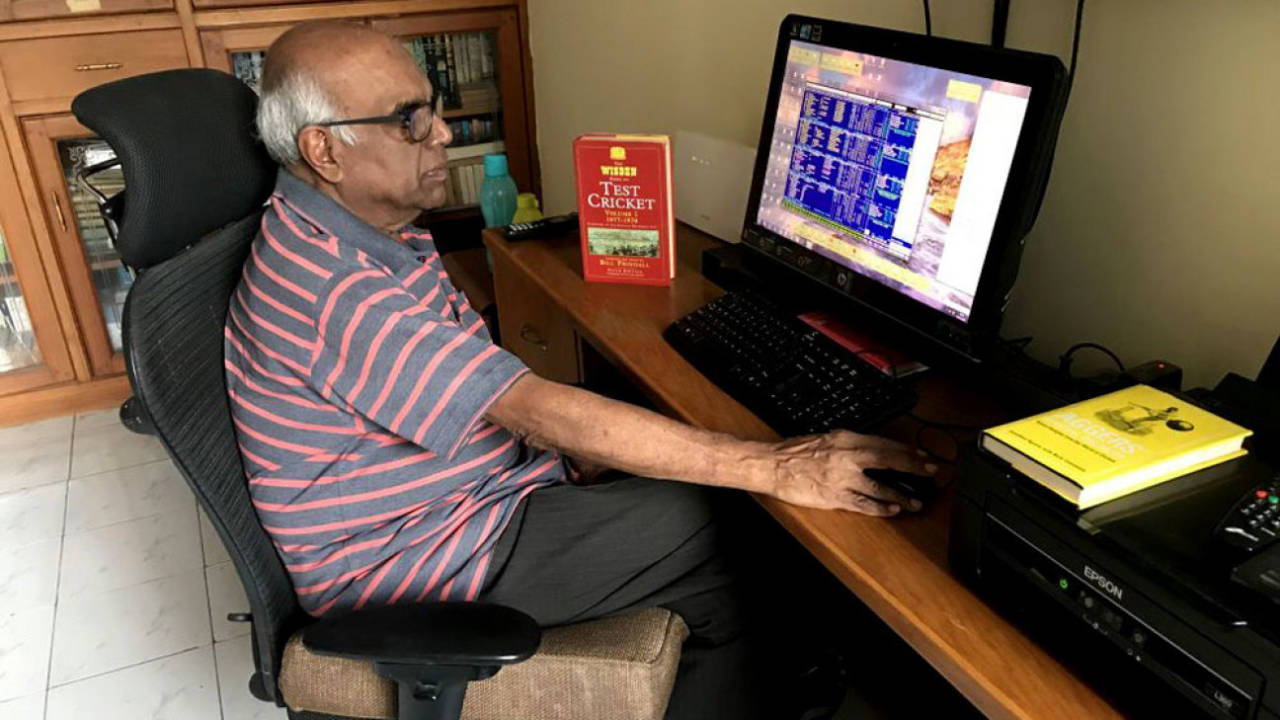

The author regularly analyses statistical trends in the game on this website and elsewhere • Anantha Narayanan

Today, I can watch four Test matches being played across the world on the same day - say, in Perth, at Eden Gardens, at The Oval and in the Caribbean. I can also follow these games on my desktop and phone.

Let's rewind to about 60 years ago. On January 7, 1956, Vinoo Mankad and Pankaj Roy shared a world-record opening-wicket partnership of 413, against New Zealand in Madras. I got to read about the feat only the next evening.

How my cricket-watching days have changed in half a century or so.

The newspaper era

In the '50s and '60s, newspapers were the only means of knowing what was happening round the globe, in politics, business or sports. There were avid readers like my father who would spend around two hours every day reading the newspaper from the top left of the first page to the bottom right of the last page. That was great value for maybe a fraction of a rupee.

In the '50s and '60s, newspapers were the only means of knowing what was happening round the globe, in politics, business or sports. There were avid readers like my father who would spend around two hours every day reading the newspaper from the top left of the first page to the bottom right of the last page. That was great value for maybe a fraction of a rupee.

The Hindu was printed in Madras by 6pm. We lived in the Nilgiris, about 600 kilometres away, and the newspaper travelled this distance by train and bus to be delivered to our homes well after noon the following day. The first reading opportunity went to my father, at 5pm. With luck, I could get my hands on the newspaper after I finished my homework, at 8pm. Which meant I could only read about what had happened in a Test the previous day 30 hours after play ended.

What about a Test played in England? Well, the Dak edition of the Hindu went to press with a report that covered play up to and including the pre-lunch session. By the time I read it, it would be past lunch in the next day's play. Former Australia opener Jack Fingleton, who wrote the reports, would include the details of the day's post-lunch play in his report for the next day. So I read about the post-lunch play on a Monday on Wednesday night.

That was how the world moved in those days. Newspapers were treasured and their contents were gold. To read the great reports, albeit a couple of days later, was exhilarating, and the quality of writing more than made up for the delay.

I think the first cricket-related news item I read was about Richie Benaud's 121 in Kingston in 1955. The beautifully written report conveyed the greatness of the 78-minute hundred, and maybe that's why Benaud remains one of my favourite cricketers even today.

I find watching cricket in stadiums in India a nightmare today. Aside from the discomforts, the noise, from fans and the PA, is too much to take, as is the lack of any objective spectatorship

The radio era

Our first radio set, arriving in 1957, was a huge National Echo box that my father guarded with great zeal. In addition to many musical programmes, he would listen to every single news bulletin. The programme that interested me was the 15-minute news at 9pm, which had a sports section towards the end, and I would sneak into the room to listen to it, out of the pater's field of vision. No one had the courage to ask him why he had to listen to over a dozen news bulletins daily.

Our first radio set, arriving in 1957, was a huge National Echo box that my father guarded with great zeal. In addition to many musical programmes, he would listen to every single news bulletin. The programme that interested me was the 15-minute news at 9pm, which had a sports section towards the end, and I would sneak into the room to listen to it, out of the pater's field of vision. No one had the courage to ask him why he had to listen to over a dozen news bulletins daily.

After a couple of years, I could tune in to sports broadcasts from Australia, India and England. Those were the golden days of broadcasting. The commentators were legends and set standards that are unmatched today - John Arlott, Brian Johnston, Anant Setalvad, Berry Sarbadhikary, Alan McGilvray, Pearson Surita and VM Chakrapani.

The BBC was at the forefront of sports coverage and three programmes stood out. Test Match Special had the best ball-by-ball coverage anywhere in the world. Sports Round-Up was a 15-minute capsule of sports news from Britain and the rest of the world, which included the County Championship and football scores. The breadth and depth of the information conveyed in those 15 minutes was amazing. The third was Saturday Special, an eight-hour long programme that covered various sports but concentrated on cricket and football. I can still hear the crystal-clear voice of its wonderful host, the Irishman Paddy Feeny, who died in 2018.

By the late 1960s, the Hindu had revolutionised their printing technology and the facsimile of the paper, created in Madras, was transmitted to many centres by around 2am each night. The newspaper was printed and distributed early in the morning, which meant the previous day's news, up until midnight, was available to read the next morning.

Rusi Surti listens to radio commentary from the Kanpur Test between India and Australia, 1969•Antony Matheus Linsen/Fairfax Media/Getty Images

Watching cricket live

I watched my first live cricket match in October 1964, when I was visiting Madras for an educational trip from college. Despite gaining a 65-run first-innings lead, India had to chase 333 against Australia. They were 24 for 4, having lost their openers for ducks, at close of play on the fourth day. On day five, Hanumant Singh, the royal from Rajasthan, played an unforgettable innings of 94, hitting 18 fours, most of these in the V. Half a century later, I still cannot forget the classic brilliance of that innings - 94 out of 193 all out.

I watched my first live cricket match in October 1964, when I was visiting Madras for an educational trip from college. Despite gaining a 65-run first-innings lead, India had to chase 333 against Australia. They were 24 for 4, having lost their openers for ducks, at close of play on the fourth day. On day five, Hanumant Singh, the royal from Rajasthan, played an unforgettable innings of 94, hitting 18 fours, most of these in the V. Half a century later, I still cannot forget the classic brilliance of that innings - 94 out of 193 all out.

A couple of years later, I was on a training course in Bombay while working at IBM. Amid the 18-hour workdays, there was a free day and the India-West Indies Test at the Brabourne Stadium beckoned. The only ticket I could afford was for the concrete seats, priced at Rs 18 (US$ 3 approximately then) and being sold for Rs 75 ($12). When I got to the stadium on the third morning, I was happy to see that the queue was close to the entrance, little realising it had already taken a full circle of the stadium!

Replying to India's 296, West Indies had resumed day three at 208 for 4 and took their score to 421. The highlight of the innings was legspinner Bhagwath Chandrasekhar's superhuman effort: 61.5-17-157-7, similar to Anil Kumble's 8 for 141 at the SCG in 2003-04.

Since we were watching from concrete steps, we were effectively sitting on each other's footwear. Anyone foolish enough to stand up was pelted with all sorts of missiles, including bananas and their peels. And those who complained were packed off by Bombay's sturdy sons of the soil - all the way down to the fences with no way up. So we sat without getting up, subsisting on a couple of ice creams for lunch. No water, no trips to the toilet. (The blazing sun helped with that last item.)

But it was worth it. To watch Chandrasekhar bowl and Clive Lloyd, Rohan Kanhai and Garry Sobers bat, our young bodies could take all that was thrown at them. It didn't matter that my new pair of shoes changed from size ten to 12 over the course of the day.

The programme that interested me was the 15-minute news at 9pm, which had a sports section towards the end. I would sneak into the room to listen to it, out of the pater's field of vision

During the late '60s I worked in Bangalore as a systems engineer for IBM. Sadasivan (aka Chubby), a colleague of mine, was a maintenance engineer whose main responsibility was to maintain the flagship computer at Indian Telephone Industries (ITI). On a Saturday, Chubby, a state-level cricketer, was playing in a league match in the city when I received an emergency call that the ITI computer was down. I drove my almost-vintage Fiat to the ground to get him. Chubby was batting and oblivious to any amount of gesticulating from the boundary. Desperate, I drove my car to the pitch in between overs and told Chubby and the fielding captain that there was an emergency. Chubby asked me to give him five minutes. In the next two overs, he scored over 20 (almost a T20 cameo), got out, got in the car and drove like Stirling Moss to ITI.

The first Test I watched in full at a stadium was the 1972-73 Madras Test between India and England, who were captained by Tony Lewis. It was a close match - India lost six wickets while chasing 86. Their bowling was epochal - Bishan Bedi, Chandrasekhar and Erapalli Prasanna, who between them bowled nearly 172 of India's 193 overs in the match. It was tough to watch Mike Denness take nearly six hours to score 76, and Salim Durani over an hour and a half for 38. I was then recently married and my wife and I watched this Test together. To this day, it's the only Test match we have watched in full together.

For all the torpidity of that game, I find watching cricket from stadiums in India a nightmare today. Aside from the discomforts, which existed earlier as well, the noise, from fans and the PA, is too much to take, as is the lack of any objective spectatorship - often, a telling silence follows the visiting team's good performance. I am envious of people living abroad when I watch matches in New Zealand and smaller Australian and South African grounds, where fans enjoy the game from grass banks, bringing their own food. There is also appreciation for both teams.

A couple of months before this Madras Test, while on a family trip to Kerala, my in-laws too got a taste of my fandom (thankfully my wife wasn't with us). I stopped the car at the cricket ground in Kottayam, where Kerala were playing Mysore in a Ranji game. I wanted to watch Gundappa Viswanath hit a four. Given the heat and the 20 minutes we had wait to see him get that boundary, my stock with my wife's family must have gone down a lot. It was, however, worth it, since it was Viswanath.

Watching on TV

When I went on a long-term assignment to the UK in 1976, I got to watch sport on colour TV, including Geoff Boycott getting his 100th first-class hundred, at Headingley in 1977, at a time when black-and-white TVs had just entered the Indian market. The quality of the televisions, the extent of the sports coverage, and the wonderful and evocative British light-entertainment shows were unforgettable. I didn't attend any live games but I did manage to visit the iconic Canterbury cricket ground and see the St Lawrence lime tree.

When I went on a long-term assignment to the UK in 1976, I got to watch sport on colour TV, including Geoff Boycott getting his 100th first-class hundred, at Headingley in 1977, at a time when black-and-white TVs had just entered the Indian market. The quality of the televisions, the extent of the sports coverage, and the wonderful and evocative British light-entertainment shows were unforgettable. I didn't attend any live games but I did manage to visit the iconic Canterbury cricket ground and see the St Lawrence lime tree.

A fan and an analyst's best friends•Anantha Narayanan

By the late 1980s, television arrived in Indian middle-class households with a bang, especially after the 1982 Asian Games in Delhi and the 1983 World Cup win (which I mostly missed while living in Dubai). I am of the firm view that this was the greater of India's two World Cup triumphs. A month earlier, they were a nobody's team of non-entities, going nowhere, with no plans to win (thank you, John Lennon). Then they won the tournament after a tough semi-final and final. There is just no comparison to the 2011 win.

Over the last 30 years, I have been able to watch several memorable performances on TV without missing a ball - Pakistan's win in the 1992 World Cup and Sri Lanka's in 1996, the 1999 Chennai Test against Pakistan, Brian Lara's 153 in Bridgetown, VVS Laxman's 281 in Kolkata, Kumble's 10 for 74 at the Kotla, Muttiah Muralitharan's 9 for 65 at The Oval, Stuart Broad's 8 for 15 at Trent Bridge, Glenn McGrath's 8 for 24 in Perth, Ben Stokes' 135 not out at Headingley, and Kusal Perera's 153 not out in Durban.

1990: the Lord's Test, and escaping the horrors of the Gulf War

I was in London during the 1990 Lord's Test, where Graham Gooch made 333 and Kapil Dev then helped India avoid the follow-on with four successive sixes. I was booked to leave London on the British Airways flight of August 1, so I went to watch the final day's play on July 31, with India batting at 57 for 2. They soon slid to 140 for 6 and I decided I might as well save money by going home a day early.

I was in London during the 1990 Lord's Test, where Graham Gooch made 333 and Kapil Dev then helped India avoid the follow-on with four successive sixes. I was booked to leave London on the British Airways flight of August 1, so I went to watch the final day's play on July 31, with India batting at 57 for 2. They soon slid to 140 for 6 and I decided I might as well save money by going home a day early.

Fortunately there were seats available on an earlier flight, so I left the same day and got home safe. It turned out that the flight I was originally booked on left Heathrow on August 1, landed in Kuwait and never took off. The Gulf War had broken out a couple of hours earlier and the passengers were offloaded and sent to hotels while the plane was destroyed. The passengers were stuck in Kuwait for over 30 days and finally reached home after suffering many hardships, including serious illnesses in the case of some of them.

If India had been 140 for 3, I might have stayed and been on the ill-fated flight, so I have to offer some left-handed thanks to the Indian middle order, a very good quartet (Sanjay Manjrekar, Dilip Vengsarkar, Mohammad Azharuddin and Sachin Tendulkar), for their failures that specific morning.

The internet era

By 1999, I had set up a company with Kumble and his brother Dinesh, and during the 1999 World Cup, we did something unique. Immediately after the toss, we simulated the match result and posted our prediction on our website. The simulation was done using my programs and based on captaincy strategies decided after the toss. Of course, no one could have predicted the outcome of the two upset wins by Zimbabwe, but we achieved over 90% success rate in our predictions.

By 1999, I had set up a company with Kumble and his brother Dinesh, and during the 1999 World Cup, we did something unique. Immediately after the toss, we simulated the match result and posted our prediction on our website. The simulation was done using my programs and based on captaincy strategies decided after the toss. Of course, no one could have predicted the outcome of the two upset wins by Zimbabwe, but we achieved over 90% success rate in our predictions.

My decade of work with Wisden started around the turn of the millennium, and my Wisden 100 list (a ranked list of the best Test innings of all time), launched in 2001, caused an uproar because of the absence of a Sachin Tendulkar innings. Established writers did not take the trouble of finding out why Azhar Mahmood's 132, Clem Hill's 188, or Kim Hughes' 100 were ranked as high as they were. But it was wonderful that Wisden stood behind the whole concept totally.

The flight I was originally booked on left Heathrow on August 1, landed in Kuwait and never took off. The Gulf War had broken out

Through Wisden, I did over 100 television shows with Doordarshan, covering tours of India by England, West Indies and Zimbabwe. Some of my analytical presentations - session analysis, balls in control, wicket-taking balls, sub-innings scoring rates, head-to-head analysis, etc - have found their way into today's cricket data analysis. I had the good fortune to work with Charu Sharma, an excellent sports anchor, and eminent players such as Gordon Greenidge, Farokh Engineer, Abbas Ali Baig, Tim Robinson, L Sivaramakrishnan, Saba Karim and Paul Strang.

We were scheduled to work on an India-Zimbabwe day-night ODI the day Nathan Astle hit the fastest Test double-hundred, against England in Christchurch in March 2002. Astle walked in at 113 for 3 and scored 222 out of the 338 runs New Zealand made while he was at the crease. He walked, not on water but across a volcano. England were totally overwhelmed and conceded 423 runs in 83 overs, although they managed to win the game. Fortunately the match ended before we had to leave for the studio, and I had the satisfaction of talking about this modern classic during the programme.

I also simulated a five-Test series between an all-time England XI and Rest of the World XI for the London Times in 2002, with the great cricket correspondent and commentator Christopher Martin-Jenkins selecting the teams and coordinating the writing. We restricted ourselves to post-war players, and the teams, captained by Peter May and Garry Sobers, "played" Tests at Lord's, SCG, in Bridgetown, Cape Town, and Calcutta. The result was a 3-2 win for the RoW XI.

Over the last ten years, I have written over 200 articles for ESPNcricinfo and built a relationship with readers across the globe. Their feedback and contributions have only enriched my writing further.

We have gone through many generations of players and methods of coverage in my six decades of watching the game. Today, cricket followers are blessed with vast amounts of well-packaged information about the game that they get at negligible cost.

While the quality of writing on websites has improved a lot, the shelf life of these pieces is about a day, and the sheer number of articles published makes it impossible to keep track of them.

I long, maybe not for the tough '60s, but for the '80s, when it was possible to visit a ground - notwithstanding the lack of facilities there - and also listen to lucid and great commentaries of broadcasting giants and then read beautifully written match reports on paper. But the game of cricket has given me so much pleasure that I would not want to change anything in my life.

Email me with your comments and I will respond. This email id is to be used only for sending in comments.

Anantha Narayanan has written for ESPNcricinfo and CastrolCricket and worked with a number of companies on their cricket performance ratings-related systems