Australia: an infatuation

What was it about them that made them the team to follow for an Indian boy growing up 30-odd years ago?

Krishna Kumar

14-Jan-2012

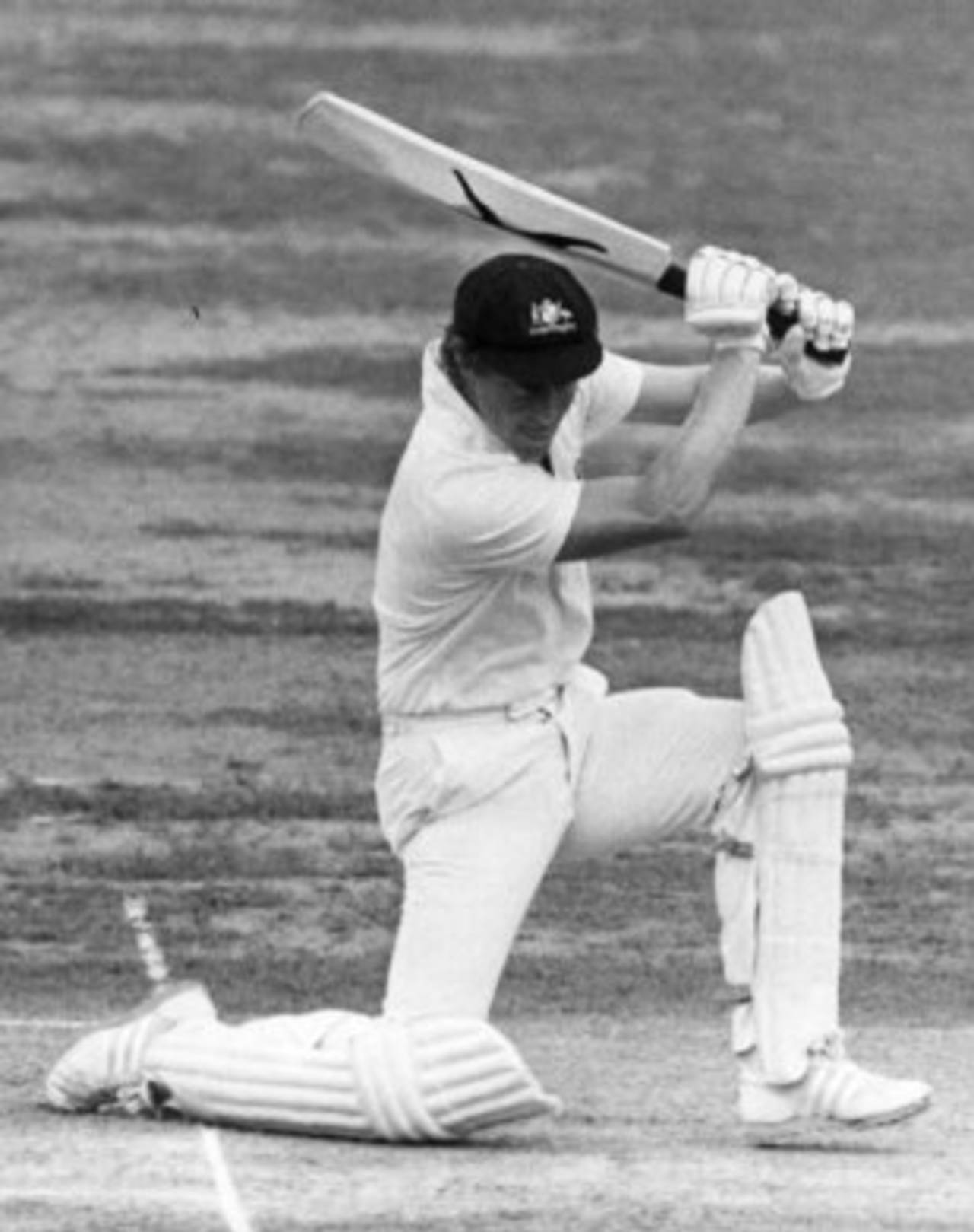

Kim Hughes: radio star • Getty Images

Everything used to be big. When I grew up, in the '70s and the early '80s in India, short-wave radios were relatively large. Newspapers were, sports magazines were. As a kid you spent a considerable amount of time just looking at the large photographs. You learnt about sport that way. As you absorbed the tableau-like quality of these photographs, you enjoyed sport for its sheer visual delights. Sport grew on you. Unhurriedly, without interruptions, vivid in the imagination.

Radio commentary made the pictures come alive, and added a touch of drama. Richards hooking, courtesy Adrian Murrell and Patrick Eagar, the SS Jumbo, and later the V100, maker's name proudly facing the viewer. When Jim Maxwell described Richards hooking Lillee, this picture, previously tucked away, unfurled and assumed flight.

As a kid you tended to develop sporting heroes purely on instinct. And as you associated teams with heroes, national boundaries blurred a bit. Since radio was the only source of live information, instinct was perhaps honed by the commentary that caught your fancy the most. Radio Australia in my case. Alan McGilvray sounded wise, but Maxwell made cricket exciting for a young kid. As he described Kim Hughes swing to leg, or dance down the pitch to hit straight, feet moving in a light scissoring motion, your hair stood on end. Rodney Hogg turning at the top of his run at the Vulture Street end before steaming in to bowl, first thing in the morning, India time, during the 1978-79 Ashes, was incredibly exciting. It didn't matter one bit that Australia were beaten soundly in the series.

In those radio years, we had a Philips set. It had a small, roughly triangular break in the glass that enclosed the dial. That was where the knob that changed the bands met the glass. Medium-wave was when the knob pointed upward. This was mostly used for home Tests. Nine forty-five in the morning during a home series meant time to switch the radio on. Listening to the long, high-pitched beep before live programming began was a special thrill. When the beep gave way to the All India Radio signature tune, you moved a little closer. When the announcer said, first in Hindi and then in English, that you were being transferred to the Test match venue for live commentary, you felt a small tingle run up your spine.

Fine-tuning into Radio Australia wasn't too difficult on our radio, since the 13m band was at the extreme left on the dial. You simply turned the dial so far left that the needle actually stood up a bit - the twine that tied the dial to the needle could stretch only so much. There's nothing that quite matches the feeling a kid gets when the first thing he does on waking up is fiddle in the dark with a radio dial. Ears straining expectantly for McGilvray and Maxwell, he is, as philosophers would say, one with the radio. It is not dissimilar to what athletes feel when they are in the zone.

In the '80s, the World Cup served as a kind of cricketing exclamation mark between luxuriously scheduled tours, the year-ending Benson & Hedges tri-series in Australia, and random one-day series in Sharjah. The calendar had a certain clarity to it. Nations toured each other, they played domestic sides, fans got to learn geography and time zones. The late afternoon breeze from the Hooghly made the ball swing; so would the Fremantle Doctor. Headingley would bring in the clouds, and Mike Hendrick. It seemed to rain every afternoon in Guyana; inconsequential hundreds would be made. Melbourne and Sydney would mean you had to get up by 5:30am. Perth, on the west coast, would give you a little more leeway - you could sleep till 8. No alarm ever worked better than a Boxing Day Test.

The first Australia-India series I remember following closely was the 1977-78 one. All India Radio used to send its commentators to cover overseas tours, and you knew all this because, even as lower-primary school students, you read newspapers closely. Well, to be truthful, the sports pages of newspapers. And so a bunch of us used to get up early in the morning - and often a few times during the night - just to make sure we didn't miss the first ball.

Perhaps it was something that the commentators said, but Peter Toohey caught my fancy the most. Bob Simpson came back in from the cold; Packer had netted the first line of stars. Sunil Gavaskar was the exact opposite of Virender Sehwag, in that he seemed to always score hundreds in the second innings. Bedi, Chandra and Pras relished Melbourne and Sydney, and there were a couple of very close-run chases by India, although I remember only the Adelaide one. There was the quaint night-watchman intervention by Tony Mann. The series was extremely closely fought, and the only thing that took away from its sheen was the missing frontline Australians.

Radio Australia having worked its magic by then, my Australia bias was in full bloom for the India home series in 1978-79. The Sportstar ran an interview with the Australia coach, Bob Merriman. One line stands out in memory. "What more do you want than [Dave] Whatmore?" he was asked. His answer "Ten more Whatmores" cracked me up quite a bit then, I must shamelessly admit.

There's nothing that quite matches the feeling a kid gets when the first thing he does on waking up is fiddle in the dark with a radio dial. Ears straining expectantly for McGilvray and Maxwell, he is, as philosophers would say, one with the radio

India were just a bit too strong for the Australians, minus their Packer stars, although Allan Border and Hughes did their growing reputations no harm at all. Geoff Dymock and Karsan Ghavri were a touch of the exotic, at a time when left-arm fast bowlers were few and far between. Mohinder Amarnath, in an odd sola topee, fell on his wicket attempting to hook Hogg. It made for a particularly striking photograph that everyone who followed cricket then must remember.

I became a complete Kim Hughes fan. Something about him in baggy green, lofting spinners down the ground, seemed to define cricketing majesty. The Australian cricketing form - sharp, clean, straight lines - painted cricketing dash and grandeur. The fine, straight-backed elegance stimulated my childhood sense of the aesthetic. The subtle captivation of the wristy, curved, wispy, dreamy Indian cricketing rhythm was to come much later.

With the returning Packer stars, plus Hughes and Border, Australia dominated the 1980-81 series. Hughes famously dedicated his double-century at the Adelaide Oval to his newborn twins. Lillee and Pascoe bowled India out cheaply in the Australian win at the SCG. Shivlal Yadav (in the first of two worthy contributions to Indian causes in Australia; he was to return a couple of decades later, as manager) and Ghavri hung on by the skin of their teeth in Adelaide. And Doshi and Kapil pulled off that memorable heist at the MCG. This seemed to trigger a kind of nerviness in the Australian teams of the '80s, and even through to the early '90s. You could count on the Aussies to stuff a chase of 100-odd runs any time. Botham, Willis, and even Fanie de Villiers, should perhaps thank Doshi, Kapil and the MCG for setting up that sneaking sense of doubt. This caused me no small sense of despair, as every time I supported Australia then, in chases that should have been easy strolls in the park, I ended up on the losing side. Well, okay, Australia did, but you know what I mean.

After MCG, India and Australia somehow contrived not to play each other in Tests for the first half of the '80s. There was a clutch of one-dayers in between times. India dominated the 1985-86 drawn series in Australia, and should have won it, except for some inopportune rain and skewed umpiring. Their batting began to look utterly dominating, especially against the next generation of Australian quick bowlers. Craig McDermott, Bruce Reid and Merv Hughes were just about starting out and often came up short against Srikkanth, Gavaskar, Mohinder, Vengsarkar, Azharuddin, Shastri and Co.

I still backed the Aussies, especially McDermott. There was something about his run-up - jaw set in firm, aggressive intent, arms rhythmically pumping, right wrist cocked, left arm readying itself for the final leap at the crease - that defined the strong, aggressive fast bowler. The face cream helped as well.

The Indian batting at this point had the right mix of experience and youth, and all fast bowlers suffered in comparison to the magnificent West Indians, Imran and Hadlee. Nothing the Australians threw at the visitors fazed the Indians in the slightest, exemplified by the large totals they made in Australia, and in that brilliant last-innings chase in the nail-biting tie in Madras.

Somewhere around this time, I developed Indian cricketing heroes, starting off, somewhat strangely, with Maninder Singh. Something in his beautifully co-ordinated left-arm spinner's action introduced me to the Indian cricketing form. Everything in Maninder's action was about rhythm. And about curves. From that smooth turn at the top of his run, till the arms uncoiled in that wonderful springy arc and the ball was released in a delicious loop, and seemingly gained pace off the pitch. My cricketing sensibilities then onwards started to respond to the Indian rhythm and form. Maninder's spin and then Azhar's wristiness, slowly, steadily drew me India's way. Eventually the arrival of a certain Sachin Ramesh Tendulkar completely weaned me away from Australia. But I'm getting ahead of myself.

Tendulakr's Perth special in 1992 moved even the staunchest Aussie supporters to cheer for him•Mid Day

Thereabouts, after being down in the dumps almost interminably in the early Border years, Australia started winning, slowly at first, then with increasing regularity, and eventually everything in sight, and India slumped mightily. It all started with that 1987 World Cup in India.

When the tournament came to the subcontinent for the first time, it was full of tight scraps. Perhaps, it was the outfields, perhaps the flat pitches, which needed the fielding team to really throw themselves about to get people out. Everyone ended up looking dusty, dirty and sweaty. Most times Border looked like he couldn't see through the grime in beard and eye. After years of grit and loss, when he seemed to be the only Australian batsman around, he emerged from the rubble with the nucleus of a team that would eventually go on to dethrone the West Indians as champions in all forms of the game.

The 1991-92 series in Australia was dominated by McDermott, Mike Whitney and Merv Hughes. Azhar hit one thrilling hundred, in Adelaide. But it was Tendulkar's boy genius that shone like a lone star. The WACA was graced by an innings of brilliance. Everything else looked pedestrian in comparison. I was hooked, like the rest of the nation. A couple of years earlier Sanjay Manjrekar had replaced Gavaskar as India's most technically equipped batsman. R Mohan's descriptions of Manjrekar's technique in the Hindu bordered on the lyrical. With his straight-batted flick, Manjrekar became the latest addition to my pantheon of Indian cricketing heroes. But he too failed in Australia.

Around this time I happened to become a graduate student in Montreal. I guess in a foreign country you do become more aware of your roots. Watching cricket in sports bars, braving winter, in the cricketing backwater of Rue Jean Talon, I lost whatever was left of my Australian bias - strangely when Australia had begun dominating all and sundry. But I suppose that has got to be a story for another time.

Krishna Kumar is a software architect in Bangalore who maintains that the best way to keep awake in meetings is by playing the Laxman air-cover drive