Tendulkar, an expat's solace

Just when an Indian who moved to the US felt his connection with cricket grow weaker, a 16-year-old batting prodigy made everything all right

Samir Chopra

Dec 6, 2013, 4:02 AM

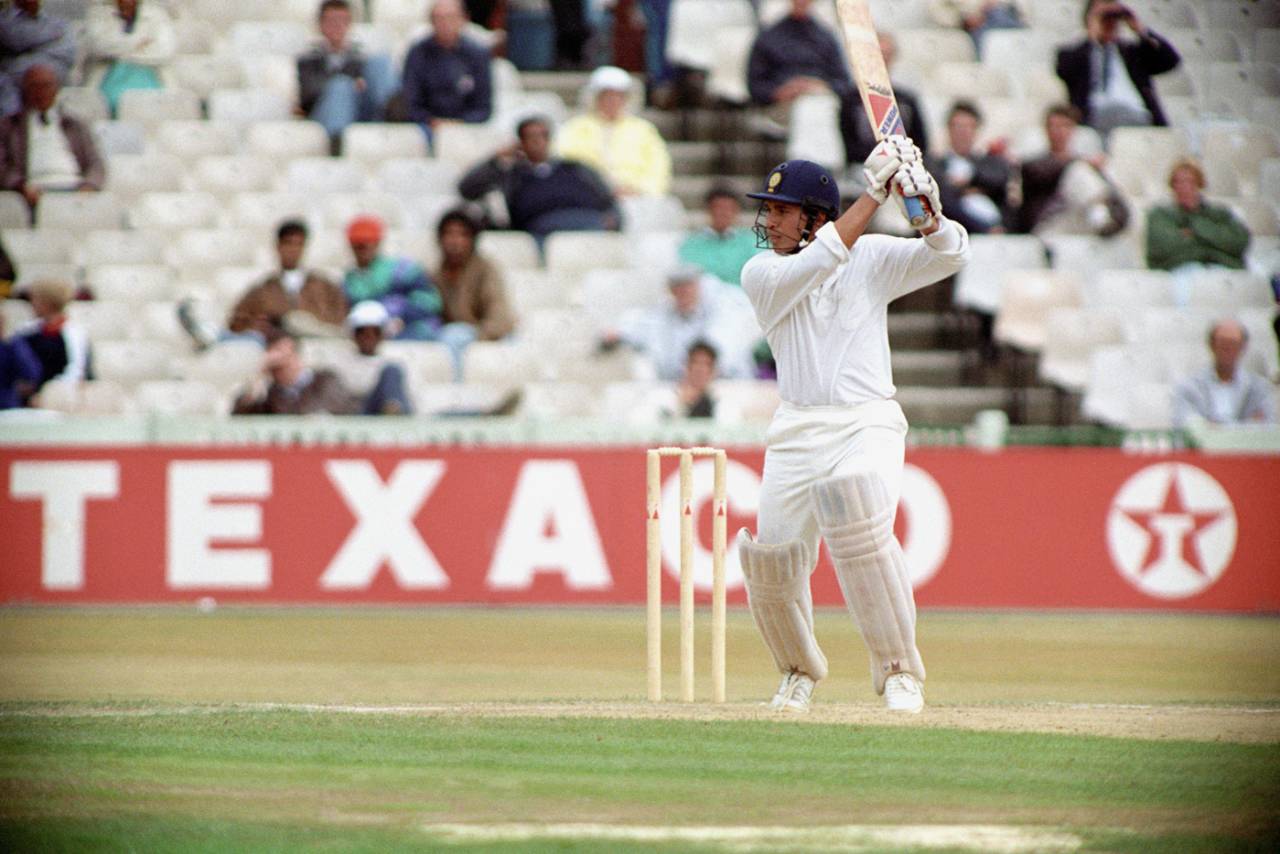

Sachin Tendulkar saved Gavaskar fans from slipping into a state of permanent melancholy • PA Photos

On March 17, 1987, I returned home from my classes at Delhi University just in time to catch the closing stages of the fifth Test between India and Pakistan. With the score at 180 in India's second innings, Sunil Gavaskar was out for 96 in his last Test innings. India were still 41 runs short of the winning target of 221; when Roger Binny fell, 24 runs later, they were still 17 runs adrift. With that win, Imran Khan realised his dream of winning a Test series in India; with that loss, Gavaskar's Test career came to an end. Like the Don, he had been thwarted four runs short of a landmark.

For as long as I had known cricket, Gavaskar had been at the centre of it. So as I watched the jubilant Pakistan team scamper back to the pavilion, I was dimly aware of a very real melancholia: an era had come to an end. And a part of my life with it.

Almost exactly six months later, on August 15, 1987, I left India for the US. From now on, my identity would be that of international student, non-resident Indian, high-technology immigrant worker; a veritable array of alternative conceptions of myself. One integral part of my older self seemed to have been left behind: cricket fan. The years 1987-1989 were a cricketing wasteland, populated only by the occasional score update from a variety of sources. I felt cricket slipping away at the margins, worrying all the while that a large and important part of my life would be consigned to the status of a faded memory.

The end of Gavaskar's career, marking the culmination of a very particular period in Indian cricketing history, and the start of a new life in distant and cricket-less lands, seemed to have coincided.

Then, one day in 1989, as was our habit, my room-mates and I drove to JFK airport to pick up an Indian graduate student, one headed for studies elsewhere. He was a friend of a friend; our job was to shelter him for the night and then send him on to his final destination elsewhere in this huge land that had become our new home. Soon after we plied him with questions about the land we had left behind, he dropped his bombshell: "Ek naya Gavaskar aaya hai [A new Gavaskar has come]."

Really? Who? Where? How?

We were provided with the bare essentials: a 16-year-old lad from Bombay was soon going to make his Test debut against Pakistan, shortly after setting the domestic scene afire. He was the best thing since sliced bread, the cat's whiskers, all of it. He was, after all, the naya Gavaskar.

A year later, Sachin Tendulkar had made his first Test ton, against England. Two years later, he had scored his epic ton in Perth. A pattern had been set; wickets fell around him; Tendulkar endured and flourished. Another two years on, and Tendulkar the best one-day opener of all time had been set loose. The party was well and truly on.

I did not lose that part of myself that had been formed by cricket. Thanks to Tendulkar and his placement at the centre of the Indian cricket team, it acquired a new focus. A new era seemed to have begun. Tendulkar became the symbol of an India that was carrying on just fine without me; he became, as has been described by so many, in so many different ways, the repository of the new hopes of the Indian who lived overseas and clung to an imagined land via a real game. In this dual arrangement of make-believe, Tendulkar was always refreshingly solid. No matter where I saw him: movie theatres, restaurants, coffee shops and bars in Brooklyn, Queens and Manhattan; my computer monitors at home; televisions in living rooms and bedrooms in Indian homes; the SCG and the MCG; he went on reassuring me that cricket would be the game I remembered it being.

Over the years that I watched cricket from here in the US, Tendulkar's cricket acquired an aura of its own. He was the child of satellite television, a man whose diminutive physical stature was blown up into an electronic presence of unimaginable proportions. (On my trips back to India, he was even more present, grinning at me from billboards everywhere.) He dominated scoreboards and games; he made me go to bed after he had been dismissed. I held him to impossibly high standards; amazingly enough, he met most of them.

Last month, more than two years after I felt he should have retired, he did so with dignity and grace, delivering a classy farewell speech with the same style that marked his best innings. I felt yet again, the sense of a curtain falling, not just on a career but on a part of my life. I have new responsibilities; time for cricket seems limited; perhaps the end of Tendulkar's career marks the end of a particular absorption in the game for me.

Perhaps. Or perhaps my relationship with the game will morph as it has done over the years. Cricket is not what it was when I lived in India; it's not what it was when my only means of consuming it was via the standard routes of print, radio and television. And I'm not the person who left "home" more than 26 years ago. One man's career spanned - almost entirely - this change in my life. Perhaps someone else will show up to tag the next stage.

An Indian fast bowler this time?

Samir Chopra lives in Brooklyn and teaches Philosophy at the City University of New York. He tweets here