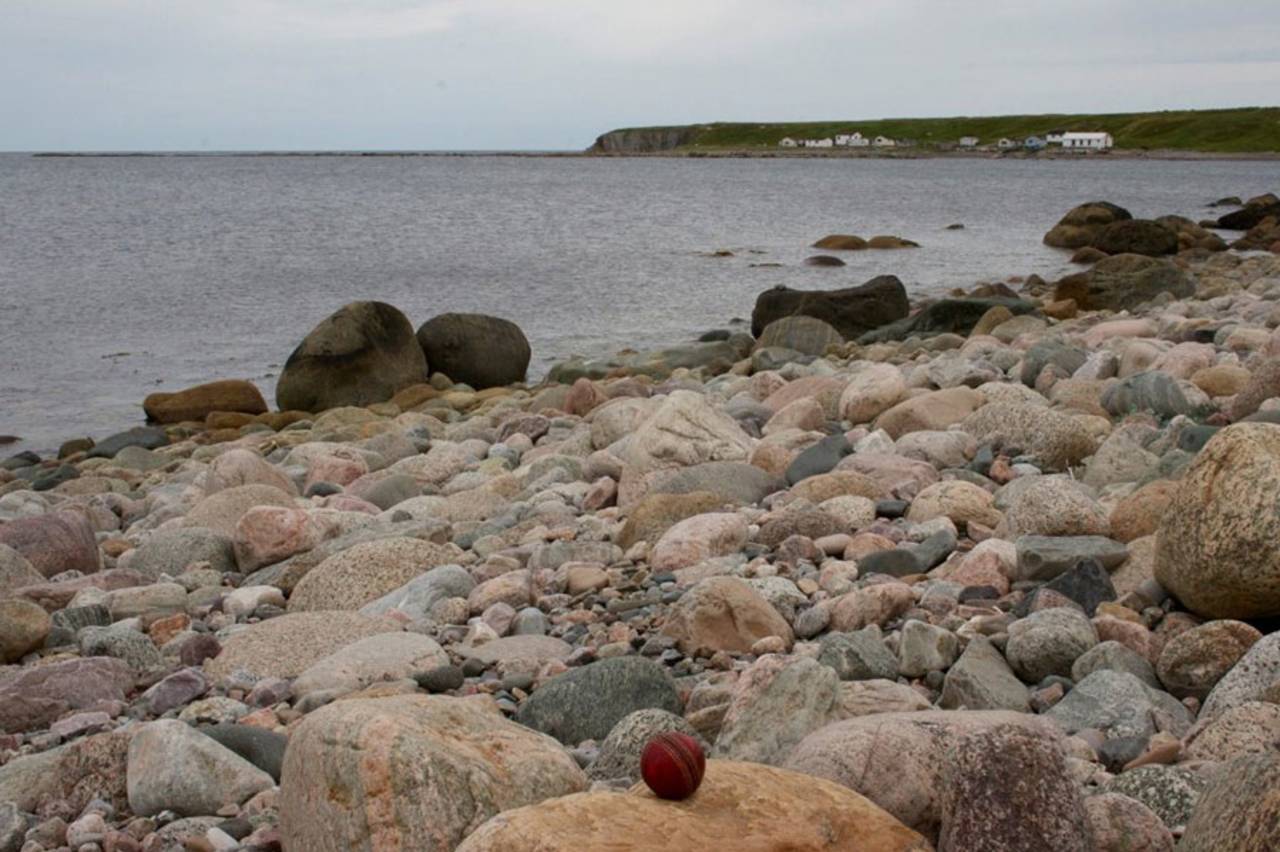

The absent cricket ball

A cricket ball at home would make daydreaming a little easier; its concrete, tangible presence would make intangible visions easier to construct

Samir Chopra

24-May-2014

A cricket ball can be a souvenir, a memento, an icon • Liam Herringshaw

I own cricket books and cricket videos. I own items of clothing used for playing cricket; my whites, still bearing traces of detergent-resistant stains caused by cricket balls and the grasses of many North Sydney cricket grounds, are neatly tucked away in a closet in my bedroom.

But I don't own any cricket equipment: no bats, balls, gloves or guards; everything I used to play cricket when I played it last came from a common pool of club-owned equipment. Of all these missing implements of cricketing destruction, I think I miss a cricket ball the most.

I wish I owned one of those proverbial leather spheres, one I could keep on a bookshelf in my apartment, sitting squarely in front of the spines of a few tomes, obscuring their titles. If I did own one, I would be able to occasionally pick it up and sense its old, familiar, five-and-something ounces weight; I would be able to run my fingers over that lacquered leather, over its hard, threatening seam, the bit that bites the pitch and fizzes off it, that shreds eyebrows, that gets raised and plucked by the fingernails - and bottle-tops - of rogues the world over.

I would toss it up a bit, twirl it around, perhaps getting it to balance just for a microsecond on my fingertips, instantly conjuring up older unrealised fantasies of bowling legbreaks. (I never learned how to bowl legspin; instead, I bowled googly after googly, effortlessly bowling offspinners with a legbreak action, vainly telling all who praised my bowling that I was just an incompetent fraud.)

I could pretend I knew how to bowl an outswinger and inswinger, pointing my fingers towards an imaginary slip cordon waiting for edges aplenty. I could imagine - just for a second or two - that I was Jack Iverson and try to fold a finger under the ball and flick it out. I could conjure up visions of standing at the end of my run-up, the quivering batsman many yards away, awaiting the inevitable extinguishment of his upstart innings.

The cricket ball would be useful for demonstrations, put on for the benefit of those that knew little about the game. I could show my American friends just how hard the ball was, so they could understand why it was such a fearsome thing in the hands of West Indians in years gone by, why batsmen wear pads and gloves and helmets, why the hook off the eyebrows was such a brave stroke. I could show these novices why bowling spin and swing and seam were such black arts, why they took so much practice and effort to get right. Perhaps I could even show them why taking catches at slip and point, in the gully, or close to the wicket, could be so difficult and require so much skill.

If these cricketing initiates were really up for it, I could walk the more sporting types the ten or so blocks down to Prospect Park and make them go through a little catching practice, and just to be a little mischievous, make every other throw just a little harder so that the red ball would smack into their palms with that satisfying "splat", and cause, just for a second or two, a species of delicious hand-wringing and rubbing. Perhaps the persistent endless ribbing about the game and its emasculated, "wimpy" players would be brought to an end by these incontrovertible proofs of the fearsomeness and intractability of the cricket ball.

Mostly, of course, as my opening lines show, I'd like to have a cricket ball at home because it would make daydreaming a little easier; its concrete, tangible presence would make intangible visions easier to construct. It would make the reconstruction and re-staging of imaginary Test matches a little more possible. A cricket bat would do this too, of course, but it would not allow for the claiming of bragging rights that I clearly seem to be deeply invested in.

To be sure, I couldn't mark out a lengthy run-up in this small living room of mine, and I certainly wouldn't try to rocket a throw from the boundary into the waiting gloves of that imaginary wicketkeeper standing guard at the end of the hallway leading to the bedroom. Still, just the act of tossing the ball up, of transferring it from hand to hand, would tickle that part of my cranium that acts as a repository for flickering memories, some real, some imagined, of many, many games from years gone by.

A cricket ball, here in New York City, would be a souvenir brought back from strange lands, a memento, an icon of a distant religion. But it would also be a magic lamp of sorts: it would enable conjuring of many kinds, and more generously, the illumination of the ignorant.

Samir Chopra lives in Brooklyn and teaches Philosophy at the City University of New York. He tweets here