Eugenides and Adorno at the cricket

Is there any point in being sad about the Sheffield Shield's place in our culture today?

Christian Ryan

14-Mar-2012

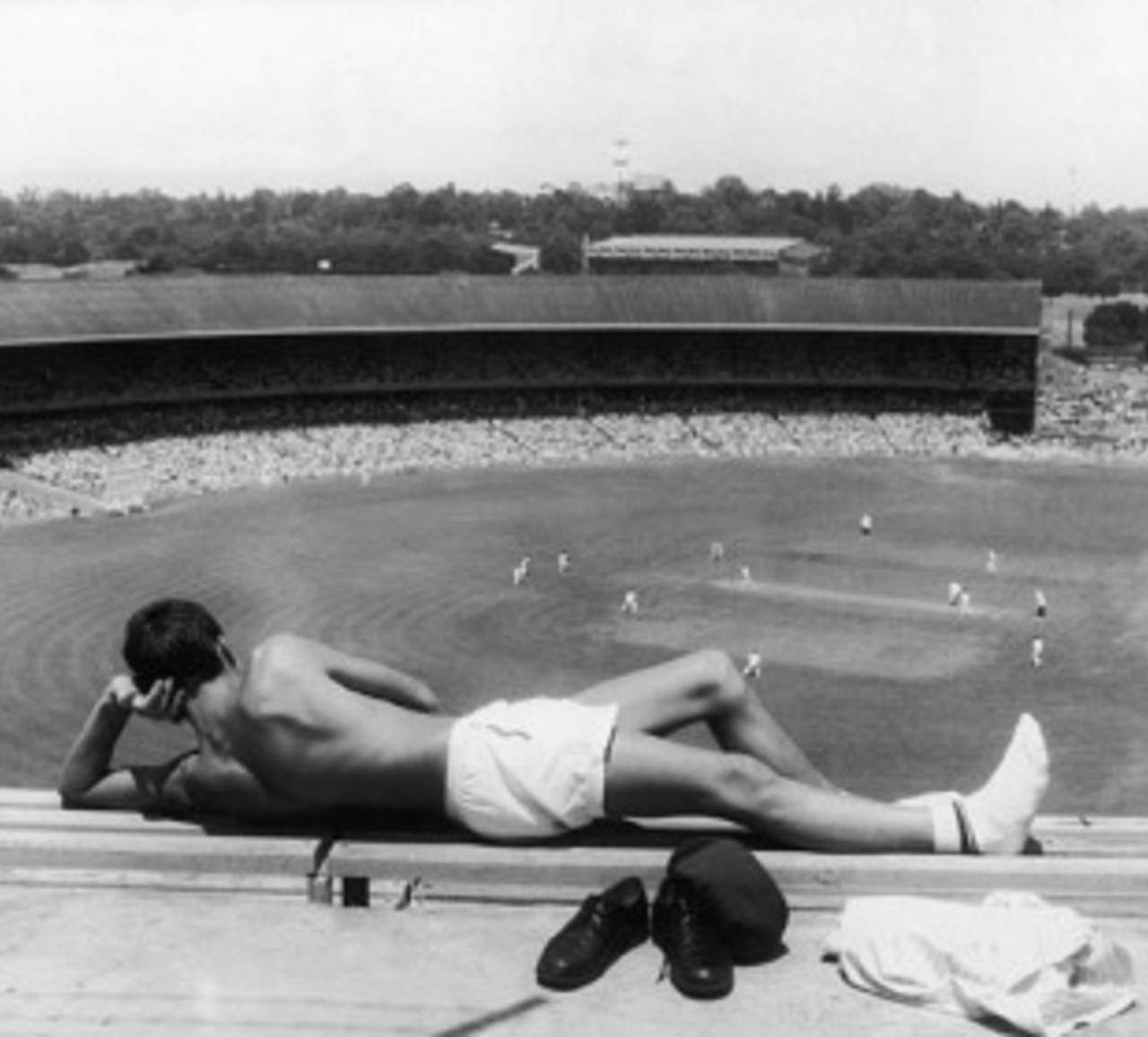

From the top tier at the MCG • Getty Images

They say a billion-plus people on the planet like cricket. If that's true, and if 12,000 a year attend Sheffield Shield matches at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, and if one-third of those people are the same people making repeat visits, and if we accept the average human lifespan in the main cricket-playing nations to be about 70, then the proportion of cricket fans who live to see cricket played at cricket's oldest international coliseum on a quiet day is 0.056%.

This is what "quiet" sounds like at the MCG: jackhammering and chainsawing near Light Tower 5, the clanging of pickaxe on metal in the vicinity of Light Tower 3, a procession of heavy vehicles emitting warning beeps at Light Tower 2.

Players' clappings and urgings, and bat touching ball… These cannot be heard.

Not last Thursday at the MCG.

A woman in a white sun-hat, not that young, is plucking her philosophy course notes out of her handbag and making some underlinings in pencil and putting them away again. She takes them back out. She has on coral lipstick, a denim skirt, sheer black stockings and below-the-knee black boots.

The lights (reading lamps?) are switched on at 2.29pm.

The day is cold: opening day of the last round of the Sheffield Shield season. If Victoria beat New South Wales, and if the results of simultaneous matches in Hobart and Brisbane fall right, Victoria will qualify for the Shield final.

The ground announcer is not announcing the scores from Hobart or Brisbane.

Ninety-four spectators sit on the grey seats in front of the sports museum.

Not the members. The members sit to the right.

Out of bounds to the 94-strong general public are roughly six-sevenths of the stadium's seats - that's the white, brown, light green, pea-green and sun-bleached blue seats. Think of reaching those seats and a gateman in a blazer bars your way.

The stumps are coloured blue, the gleaming chemical-sick pale blue of the sponsor's logo, Bupa blue.

I have packed two red apples. Eat one now and one later; or eat both later?

I spy the old WA opener Ric Charlesworth. No, it's just a fit-looking guy with attentive eyes under a baseball cap.

Tea-time. The loudspeaker is playing Midnight Oil's "Power and the Passion":

It's better to die on your feet than to live on your knees.

The sun-hatted woman's iPod earphones are in her ears when the cricketers resume. McDonald of Victoria bowls outside off, Rohrer of New South Wales plays leave-alone, and the sun-hatted woman claps. She claps again, a fingers-only clap, when Dawson lets pass the last ball of Siddle's 16th over, a maiden over.

If a clap cannot be heard, is there any point clapping?

A dozen Japanese men in suits have materialised. One, stocky-looking, is rubbing and poking at a grey seat. He asks a question. The question gets translated. A Japanese woman - previously unseen - curls out an arm and squeezes the top of a grey seat. Then a different Japanese guy plonks his body down in one, then springs back up, then turns around and flaps the grey seat-flap with his hand like he's bouncing a basketball.

Smith is out - pulling, caught at mid-off, a top-edge, top score though, 86. Once, ball-by-ball radio commentators would have sketched this 86 in graceful word pictures and newspapermen would have applied rat-trap minds to dissecting it. Tomorrow morning's paper reports, simply:

Smith prospered in seam-friendly conditions with an enterprising 86.

After ten minutes the Japanese men and woman are gone.

By 5 o'clock the 94 are down to 41.

At 5.22 the players have vanished. It's gloomy, but dry, and the lights are on. The electronic scoreboard gives no explanation. The ground announcer is not announcing why either.

Realisation hits like a slap: there is no ground announcer.

It is 5.29 and the 41 are now 15. Still no players. One of the hardcore 15 - he's grey t-shirted, despite the cold - starts up a slow handclap, which lasts for about five claps, then stops. Resolve is being tested. At 5.38 there's a welcome sight: two batsmen, in the dugout, helmeting up. The hardcore 15, unbreakable, are still in their seats.

Just 15. Yet this cricket, though barely watched, is scored by scorers, and the scores count towards players' records, and their records are published in books.

In the toilet block I take my time. Between two banks of 18-man metal urinals are a pair of eight-man urinals, none of them being used, and for a second or two's hesitation I am torn.

Climbing concrete stairs, re-entering the light, I notice that one of the hardcore 15, wavy-haired, and boozing with a pal, is the ex-pedal steel player of an old band, The Triffids. Nickname of "Evil". I look more closely. It's not him.

At five to midnight, the night before I caught the number 246 bus to the MCG for a Shield game, my girlfriend flew to Shanghai. Talk about different worlds: 94 versus 23 million. Re-boarding the number 246, there's an email on my phone.

Was really interested to find out about the Chinese Qingming festival - Tomb Sweeping Day - which is about honouring the dead and making offerings: "ghost" fake paper money, paper models of Mercs and nice suits, paper homes, all kinds of elaborate things made out of paper, which are then burnt in the name of the dead ones' comfort and prosperity. I saw fake paper cigarettes for the dead.

The last, and sixth, day of a 1907 Shield match in Sydney lasted three balls. Queuing up to see them were 312 diehards. New South Wales were after 593 runs to knock off Clem Hill's South Australia, a far-fetched chase that had begun two days earlier with the hometown crowd yelling a conversation with itself. "Are we downhearted?" one'd roar. "No," the rest would roar back.

Tomorrow I'll go back to the Shield match.

****

The clanging and sawing's softer when you are out in the middle, one of the players is telling me. You're focused. Nearly no one's watching but you barely think about that. You feel it though, somewhere, subconsciously, and yeah it'd be nice to feel that other feeling of being at an old English outground with half the village through the turnstiles and riding every ball. Even a decent-rank park match in Australia - your team-mates, their girlfriends, their girlfriends' dogs, no fence or gates, just rope, everyone close-by and noisy and giving off a sense true or otherwise that what's happening matters... Getting picked in the Shield and striding the giant TV arenas is a thrill. Then it's normal, and soon the emptiness is normal too. You're thinking, this isn't what I practised every day of childhood for. But by this time you are also thinking: "It's a job." Anyway, you don't play for the adulation of crowds, and anyone who does, well, I can't relate to that.

So: why do you play?

You play for the challenge, and to be the best you can be.

And if the rulers ruled that no more Shield games will ever be staged at the MCG or SCG it wouldn't be that sad.

The changeover-of-innings song is INXS's "Don't Change":

I found a love I had lost.

It was gone for too long.

When the two teams playing now played in 1923 at this ground 89,386 people watched them.

Day two's din is coming from Light Tower 3. First some beeping, then scraping, rather than all machines going flat-out and concurrent. You can hear the players.

The sun-hatted woman is not here.

Some 5th XI suburban cricketers get to play on lush meadows bordered by a creek that gurgles. Make it to Shield level and to the tips of the Test team and what do you get? Jackhammering.

No one's reading.

A few fewer than yesterday's 94 are in, and plenty fewer than the 580 who went along to the last day, a Monday, of NSW v Tasmania at the SCG in October 1982. That was considered a disappointing crowd at the time. Playwright Alex Buzo was one who went. Buzo saw Mark O'Neill call Steve Rixon through for a perilous single, too perilous, and he saw Rixon walk off slapping his bat against his pad.

"I have seen a hundred batsmen walk off the SCG and slap their pads," said Buzo, "but this is the first time I have heard the slap."

****

The last, and sixth, day of a 1907 Shield match in Sydney lasted three balls. Queuing up to see them were 312 diehards. New South Wales were after 593 runs to knock off Clem Hill's South Australia, a far-fetched chase that had begun two days earlier with the hometown crowd yelling a conversation with itself.

"Are we downhearted?" one'd roar.

"No," the rest would roar back.

That crowd could bend a match to its will - the way, just occasionally, a cricket crowd can. Once the score hit 521, they cheered every run. On 533 a not-out batsman, Carter, glanced at the pavilion. "Bring Carter a drink." With the final morning upon them, the score was 572 and the last man in action. Last man, alas, had only three balls left in him.

Saturday is different, the jackhammerers' day off. The batsmen are attacking and a left-arm spinner is attacking them back. Only two men in the deep.

It is like sitting in a poem.

This is merely the third morning - though everyone knows there'll be no fourth - and the people in the grey seats do not add up to 312.

But the fence, front row, is a straggle of small boys, some with bats, all with cartons of hot chips, their dads fielding mobile phone calls.

No round-the-grounds scores from Hobart or Brisbane are forthcoming, still. But I don't hear any wonderings or murmurings. People are not here to see if the Vics can reach the Bupa Sheffield Shield final. People are here just to see.

It's a job.

Yet when Finch of Victoria falls lbw it doesn't seem like job insecurity that's making his bat stab scuff marks in the grass as he goes, angry; and when he cover-drove the previous ball for four, even though you couldn't see his face behind his helmet grille, something in his shoulders lifted, happy.

Happy.

Three are reading - Eugenides' latest, Adorno's treatise on the culture industry, and a 1961 social history of Victoria's western district.

I'm re-reading - a paragraph that rewards repeated re-reading:

A length ball straightens, pops and lobs into the slips off the shoulder of Constantine's bat, a catch that eight-year-old Bobby would scorn and ask please to be thrown a real one. First slip all season has been beside himself with anxiety to drop as few as possible of the balls that fly towards him. This lob takes him by surprise and he muffs it. Constantine jumps with joy like an eight-year-old…

- CLR James, Beyond a Boundary, 1963

No crowds, no attention: another day at the job•Getty Images

The sun-hatted woman is back. Her white sun-hat's a white lawn bowls hat, and her shoes are white lawn bowls shoes, stockings skin-coloured and skirt a faded denim.

Her wrinkled sparrow's-feet hands clap each boundary home hard.

Across from her sits a man. "Good boy," he says after every good shot.

Across from him sits another woman who is describing curiosities in the play to a bearded man who cannot see clearly.

A three-minute hiatus; the ball, says the woman, is beaten out of shape and the umpires are sifting through a bag for a similar-aged replacement.

Another hiatus, longer; the ball, this time, has been straight-hit into the sun-bleached blue seats where no one sits and so no one can throw it back.

"Better here," the woman says, "than being at home watching a film. Isn't it?"

"Fresh air," the man who cannot see clearly agrees.

Is there any point in being sad about the Sheffield Shield's place in our culture today?

Was there any point in the hardcore 15 staying on?

What do they know of living who only "point" know?

Christian Ryan is a writer based in Melbourne. He is the author of Golden Boy: Kim Hughes and the Bad Old Days of Australian Cricket and, most recently Australia: Story of a Cricket Country