'Kenya cricket is dead and buried'

The veteran spinner's dream spell against Australia in 2003 symbolised a brief golden period for Kenya, but since his retirement, the country's cricket has nose-dived

Tim Wigmore

30-Sep-2014

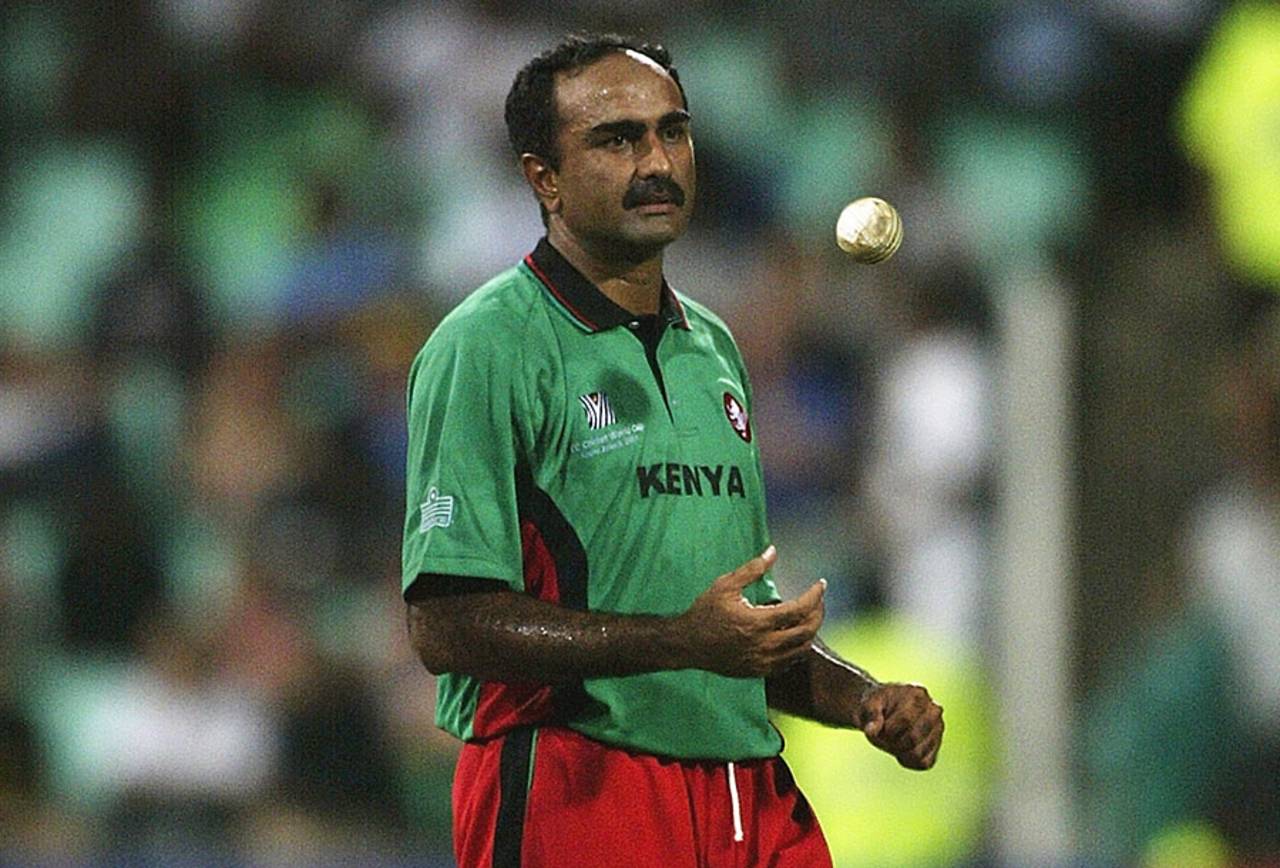

Though pushing 40, Aasif Karim was coaxed out of retirement for the World Cup, and for a while he made the eventual world champions shiver • Getty Images

Before the 1990 football World Cup, Roger Milla was playing out his career in Réunion when he received a phone call from Cameroon's president urging him to come out of international retirement. At 38, he scored four goals in Cameroon's run to the World Cup quarter-final. Aasif Karim is the closest cricket has come to an equivalent.

As Kenya prepared for the 2003 World Cup, the board implored the 39-year-old Karim to return. It was not just for his guileful left-arm spin but also for his unifying presence in the dressing room. "There was a lot of acrimony and problems to be sorted," he says. It was a forebear of the strife to come for Kenyan cricket.

Karim had already enjoyed an extraordinary life. A scion of the great Karim sporting dynasty in Kenya (a DVD celebrating them will be released in December), he had juggled a successful business career alongside playing cricket for Kenya - he remained strictly an amateur even as the leading Kenyan players turned professional after the 1996 World Cup. Karim even had time to play Davis Cup tennis for Kenya.

He retired from cricket at 35, after having captained Kenya in the 1999 World Cup. Few would have thought that his most famous performance was yet to come.

The comeback began ignominiously. Thirteen hundred and fifty-four days since his last ODI, Karim was selected for Kenya's World Cup opener against South Africa. But his two overs were thrashed for 17 and he was unceremoniously dumped.

Kenya's progress to the Super Six stage gave Karim the chance to end his career on a more triumphant note. Recalled after a month, his nine overs against Zimbabwe went for only 20 runs. Three days later he faced Australia in Durban.

A powerful case can be made that this Australia side was the finest in ODI history. They would win all their 11 games in the 2003 World Cup. But for 50 glorious deliveries, Karim reduced them to a quivering wreck. After restricting Kenya to 174 for 8, Australia were hurtling towards their target with the force of a runaway train. They had reached 109 for 2 off 15 overs when Karim was handed the ball. Ricky Ponting was on strike. It did not strike many as being a fair contest.

"We've had an incompetent administration for the last ten years. The results are clear. Where is the cricket now?"

Karim thought rather differently. "With my second ball I saw that there was turn on the wicket and that he was a little bit shaky." A classic left-arm spinner's delivery gripped and bounced, and kissed the edge of Ponting's bat. A sharp chance was put down by slip, diving to his left, but Karim was not to be deterred. "I kept putting the pressure on him and every ball he was struggling." With his fifth delivery, Karim bowled a faster arm ball that went straight on. It thudded into Ponting's back leg before he had time to get his bat down.

So began one of the most enchanting bowling spells. A man in his 40th year, a long time retired from his part-time cricketing career, bewitching Australia.

It was Barry Richards, commentating live, who provided a sense of Karim's majesty that day. After Karim had fizzed a ball sharply in to the left-hander Darren Lehmann in his second over, Richards pre-empted what was about to happen next. "He's got a slip in place for the one that goes on with the arm. You bowl one that really turns a lot and surprises the batsman. The next one goes on with the arm, he looks for the turn and nicks it to slip."

But Lehmann didn't nick Karim's next ball to slip: he edged it behind instead, deceived by a delivery straight across him from over the wicket.

Three balls later, Karim bowled a slower ball. Brad Hogg was too early on his shot, and a leading edge back to Karim was snared with agility. Suddenly his figures read 2-2-0-3. No more wickets followed, but he continued to vary his flight, pace and turn with mastery. This was an Australian side for whom relentlessly attacking cricket was the first and last resort. But they were forced to make an exception for Karim: after eight overs, he had only conceded two runs.

Kenya were still defeated, by five wickets, but Karim's performance was established as one of the most remarkable in the history of the World Cup. "It was unbelievable," he said. "After the game I must have done at least 50 interviews from CNN to Sky to all the Indian channels. I think any cricketer would dream of my performance against Australia. It came from nowhere. That is something that I treasure every day, including today. Whenever it comes up there is a smile." Few better examples of the guile and skill of orthodox spin can exist.

The World Cup semi-final was billed as Karim v India. Sourav Ganguly's brilliance against left-arm spin meant that Karim was restricted to four overs, which went for 25. After Kenya's defeat, Karim retired for good. He left international cricket with his team-mates believing that their opportunity to play Test cricket was imminent.

Karim says that he would have relished the chance. But he was never convinced that Kenya were ready for Test status, owing to the board's penchant for prioritising short-term success over the long-term establishment of cricketing infrastructure in the country.

When Kenya reached the World Cup semi-final in 2003, they had proved themselves worthy opponents for Test sides over seven years. After beating West Indies in the 1996 World Cup, Kenya became a regular presence in triangular and quadrangular ODI tournaments around the world, twice beating India. And they beat Bangladesh in six of the first seven ODIs between the sides.

Aasif Karim: "Whether it is the administration, the players or whoever it is, all stakeholders should never be forgiven for this missed opportunity [failing to qualify for the 2015 World Cup]"•ICC/Donald MacLeod

But Karim believes that, all the while, the foundations on which Kenyan cricket were built were collapsing. The development structure and domestic cricket "became weaker as we became stronger internationally". As Kenya seemed on the cusp of Test status in the years after Bangladesh's elevation in 2000, the board invested virtually all its funds into professionalising the national team and the national stadium in Nairobi. The capital hosted the ICC Knockout in 2000, and was awarded two games in the 2003 World Cup.

Karim and his team-mates in the 2003 World Cup learned the game in the competitive Nairobi club scene in the 1980s. Test players including Sanjay Manjrekar, Kiran More and Sandeep Patil were all involved. But too little was done to bridge the gap between club and international games. "If you don't have a good development structure, where are the Tikolos or the Odumbes or the other players to come from? You don't find them on the street," Karim says. "Unless you have a good structure it's very difficult to produce quality cricketers on a regular basis."

The ICC and the Full Members could have done much more to nourish Kenyan cricket. After 2003, Test sides abandoned Kenya: from playing 18 ODIs against Full Members 18 months before that World Cup, Kenya played only 11 in the three years after. Karim apportions more blame to Kenya's administrators. "Our own house was not in order," he says. Riddled by corruption charges and infighting, the Kenyan Cricket Association was dissolved in 2006, replaced by Cricket Kenya.

But administration was not Kenya's only problem. "There was also greed among the players," Karim says. "I always used to explain to them that don't run after success, because when you are successful money follows you." A year after Kenya's appearance in the World Cup semi-final, their former captain Maurice Odumbe was found guilty of match-fixing. Coupled with the off-field turbulence, the Kenyan cricket moment had gone.

Karim doesn't envisage Kenya ever having a similar chance to join the international elite. They didn't qualify for either this year's World T20 or next year's World Cup, and have even lost ODI status. "I am sure you can feel it in my voice, even now," he says. "It is beyond sad and painful.

"It is a great missed opportunity and they should never be forgiven for letting it pass. Whether it is the administration, the players or whoever it is, all stakeholders should never be forgiven for this missed opportunity."

"Kenya cricket is dead," Karim asserts. "It is dead and buried. Your intent can be good but if you're not competent to do something, it doesn't happen. We've had an incompetent administration for the last ten years. The results are clear. Where is the cricket now? My prediction is that from being an Associate team having ODI status we will become an Affiliate."

What can be done to reinvigorate Kenyan cricket? "The first thing I would do is say we are on ground zero," he says. "Number two, I would call all the stakeholders, including the past administration - there were some competent past administrators who did a very good job - and bring the past cricketers in.

"We would have a brainstorming session for a week or so to try and see how we could revive it. Then obviously the key would be to go into schools cricket, estate cricket, development cricket, and start again. If those things were done correctly and we had good, competitive cricket, we could bring back the crowd support. That would generate income because you could bring in the corporates. But minimum it would take ten years before any meaningful results could come."

During the wait, any young Kenyan cricketer seeking inspiration could do worse than recall Karim's spell against Australia. He certainly intends them to: he personally uploaded his entire spell onto YouTube.