Relentless, resilient, responsible

On Anil Kumble's birthday, a fond tribute to the man whose bowling always did just enough

MR Sharan

Oct 17, 2014, 9:53 AM

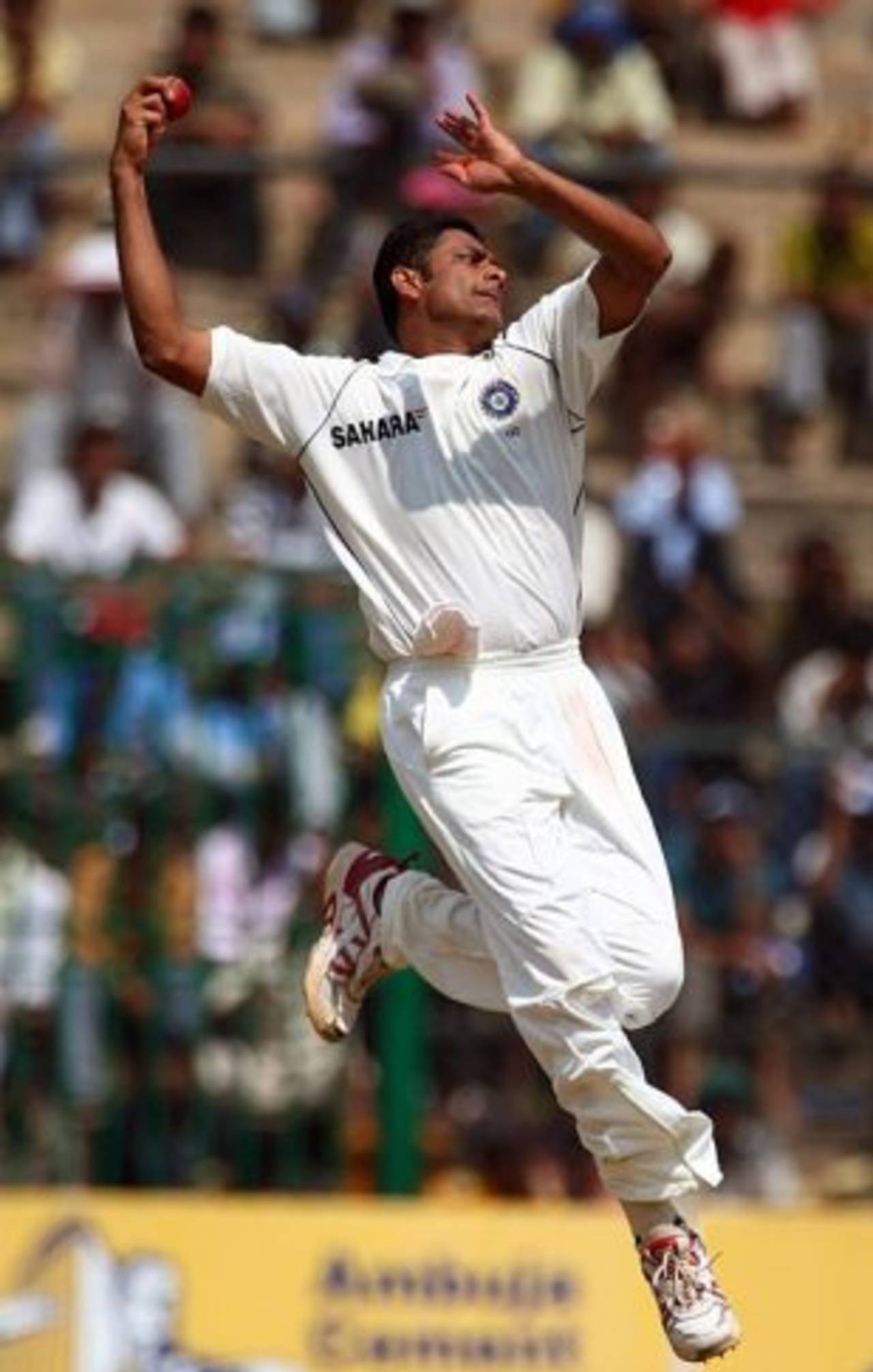

To say that Kumble's action - all arms and limbs, leaps and movement - was lovely, wouldn't be enough • Getty Images

What was it like to watch Anil Kumble bowl?

To watch him bowl in whites was to meditate. A silent, crouching space - batsman, close-in fielders, umpires - imbued with familiar anticipation; a white, slinging figure - the very embodiment of practised rhythm - shoots through; a red projectile arcs its way across, landing and doing just enough.

Rinse, lather, repeat.

Kumble's beauty was difficult to pin down and near impossible to convey. Yet, to those who persisted, rewards were plentiful. To say that the action - all arms and limbs, leaps and movement - was lovely, wouldn't be enough. To say the craft was subtle would be to state the obvious. To say he was a "wizard" or a "master" would be wrong. Hyperbole never did justice to Kumble - he being the bowling equivalent of a railway track: fundamental, ubiquitous and unappreciated - one never reached into the further recesses of one's vocabulary to describe him or his craft, one made do with what one had. It was fitting; it was just enough.

So, here is Kumble, as described a countless times: relentless, untiring, dogged. But, here is Kumble, to those who admired him: passionate, persistent, proud.

That's why I could watch him all night, toiling away in the Caribbean heat - jaw intact or broken - as the streets outside grew quiet. Kumble drew one to him not because he shone every time, but because he lived for it. When a fielder misfielded or, worse still, dropped a catch, Kumble's anguish knotted your innards: you felt it, felt the world crashing down. Yet, next ball, he would dance to the wicket again, gusto and intent intact.

And he would do it all day.

Sport allows one to give vent to a series of emotions one hides away otherwise. I once met Kumble in a small gathering of friends and family in an apartment in Bangalore. I was nine, he was a star. He sauntered around the room, making small talk and devouring packets of chips, pausing only to tell us kids not to eat chips: it's not good for you. He seemed to revel in the delicious irony of it all. It was hard to believe we'd seen this good-natured, self-effacing man on TV a million times before.

On the field, Anil Kumble was a different man. He was proud - he took great pride in playing for his country, in bowling batsmen out. Watch him celebrate a wicket: this stern, unsmiling man - an anachronism in the never-too-serious noughties - suddenly begins to awkwardly hop and skip and throw his arms up, fist clenched in celebration. Watch his face light up; it is a strange, indescribably wonderful sight. It is the sight of a modest man being proud.

One didn't only watch Kumble for the wickets, of course. He stood for everything wonderful about Test cricket: to the true lover of the long form of the game, the act of viewing bestows a certain significance to the everyday. You don't watch Test matches because every moment will shine with brilliance or like T20, allow even mediocrity to throw up sporting stories. A conversation with Test cricket is like one with a friend for life: slow, familiar, rhythmic, even the silences are comforting. Indeed, among all sports, nothing approaches life as much as Test cricket: what is life but a few big moments interspersed between long spells of repetitive, but often riveting routine? The routine builds the base for the magical; take away the routine and the magic loses context.

Like Test Cricket, Kumble was about context and rhythm: he was exciting because he was familiar, consistent and productive. At his best, like the sport itself, you couldn't take your eyes off him; at his worst - which was rare - he was still watchable.

Of memories I will carry unto my grave, the picture of a joyous Kumble in the Wisden Cricketer magazine, at the end of a great year where he captured 74 wickets at 24 including a bag-full in Australia, will be foremost. I was young and proud; that Indian team was not-so-young and proud. Everyone celebrated the batting Fab-Five - the fancy trains that waltzed across cricketing continents. Few remembered Kumble's relentless wicket-taking.

This later Kumble, whose every ball I strove to watch, was made for Test cricket. He used up the entire broad canvas the format offered. No longer as brisk as before, he turned to working batsmen over. Bowling was now a thing of logic - wickets were constructed, like a mathematical proof, each delivery placed atop another, each closely resembling but not entirely similar to its predecessor, each building towards that one ball - another deceptive not-quite-clone that would catch the edge, or beat the bat to strike right in front.

Kumble's wickets no longer doffed their hats, they shook the batsmen's hands' goodbye.

Anil Kumble's retirement was as understated as his career had been. It was a fitting finish•Getty Images

When he did doff his hat and say goodbye (and thank you very much), on a grey Delhi day in 2008, I wasn't there. It still rankles. I had made it to the previous days of that Test Match against Australia, seen VVS Laxman stroke his way to a gorgeous 201*. On the third day, Amit Mishra outbowled Kumble, Sehwag outbowled them both. There was, however, one tight spell by Kumble, full of all the wonderful qualities we had come associate with the man: relentless, resilient, responsible. He may not have produced wickets, but he conjured the odd unplayable delivery and held one end up. A friend and I sat together and we remarked that this may be one of his last great spells. It turned out to be prophetic. On the fifth day, without a warning, Kumble walked out to a guard of honour and retired.

I didn't know he would retire, and chose the drudgery of college over the final day of a dead Test match. In hindsight, I could not have made a worse decision. A voice in my head blamed the great man, wishing for once he'd been less modest and given us some notice. Sometimes, however, I tell myself that that's how it should be - a great, grand send-off would have never sat right with a man like him.

With Anil Kumble, it was always just enough.

If you have a submission for Inbox, send it to us here, with "Inbox" in the subject line

MR Sharan, a PhD candidate at Harvard, is a member of the Harvard Cricket Club and author of the novel Blue (Harper Collins, 2014). Anil Kumble has been a lifelong fascination for him