The show must go on

Two assassinations left England's tour of India in 1984-85 in serious doubt

Martin Williamson

29-Nov-2008

| ||

Early in the morning of Wednesday, October 31, 1984, the weary England touring side landed in New Delhi after a long flight from London. Within three hours the future of the tour was left up in the air after Indira Gandhi, India's prime minister, was assassinated by her own Sikh bodyguard.

In the days that followed, the side remained in their New Delhi hotel while anti-Sikh violence swept the country and politicians and cricket administrators debated what to do. Unlike today, when the players' opinions are actively sought, back then it was board officials who made the decisions and the cricketers pretty much did as they were told.

Gandhi's murder triggered a wave of reprisals and 150 people died in the immediate aftermath. Delhi was put under what the Times described as a "shoot-to-kill curfew", although the team were never in any danger. "Before any tabloids are thinking of buying a cricketer's account of how-we-escaped-the-hell-that-was-Delhi, the major danger round the hotel pool was, as ever, sunstroke," wrote Matthew Engel in the Guardian.

The Indian board acted quickly, cancelling the first two warm-up matches and recalling its team from a tour of Pakistan, although the decisions were largely influenced by the implementation of 13 days of national mourning.

Unaware of the particular sensitivities of such a high-profile death, the England management bemoaned being left with only one game before the scheduled opening ODI. It was soon made clear to them that the mourning period was meant to preclude them even from practising in the nets, although as a compromise it was decided they could do so after the official state funeral.

They were still left with nowhere to go and no one to play. "Obviously, the lads want to play cricket," Tony Brown, England's manager, said. "But we need someone to play against." A few players were reported to have gone to Brown and asked to be allowed to go home. "Brown memorably brandished the passport of an irate Allan Lamb, challenging him to take it and go home," Vic Marks recalled. Derek Pringle went further, writing in the Daily Telegraph, "To get players to stay, Brown threw all their passports on a table and told those who wanted out to take theirs and 'piss off'."

Back in London, Donald Carr, the secretary of the England board, managed a wonderful understatement when he told the media that things were "not ideal".

| ||

Attempts by the England management to work out how to proceed were further hampered by major disruption to the telephone system, making discussions with England officials in London almost impossible. Indian board officials were unable to fly to Delhi either, as air and rail transport was also seriously affected by the violence.

On November 2, the Sri Lankan board offered to host England while the national emergency in India continued. The official response was that England could not leave the country until Rajiv Gandhi, the new prime minister, had been consulted and, understandably, he had more pressing matters on his hands.

Gruelling negotiations continued on Saturday, November 3, before late in the day Brown got permission from the Indian board and government that the side could leave the country. The next day the England squad headed to Sri Lanka on board the private plane of Junius Jayewardene, Sri Lanka's president, who was returning home from Gandhi's funeral.

While the players were able to relax, with a few matches hastily arranged in Sri Lanka to help them prepare, discussions about a revised itinerary continued. The Indian board insisted on continuing with a five-Test series; Brown was adamant that would not be possible.

England spent nine days in Colombo ("they found opportunities for play and practice which would have been impossible in India", reported Wisden) before they resumed the main tour following assurances regarding their safety. Five Tests had become four during their absence.

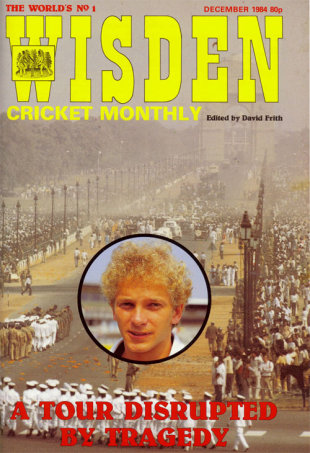

In an editorial in Wisden Cricket Monthly, David Frith wrote: "Echoes of this tragedy will reverberate heavily for years, let alone weeks, and it is unlikely the calm that was restored within a fortnight of the dire deed will be total or uninterrupted." He was not to know how soon the chaos was to return.

The warm-up games were uneventful, if not successful, and England headed to Mumbai for the opening Test. On the evening of November 26, the squad attended a reception given by Percy Norris, a cricket lover who a month earlier had been appointed British Deputy High Commissioner.

The next morning, the eve of the Test, Norris was assassinated on his way to work, within half a mile of the team's hotel. An organisation calling itself the Revolutionary Organisation of Socialist Muslims claimed responsibility.

Whereas Gandhi's assassination had been a shock to the tourists, this really hit home. "It came even harder," David Gower, England's captain, recalled, "because of his nationality, which left us feeling that much more threatened." Instead of preparing for the match, the players found themselves embroiled in another round of team meetings, although they managed to escape to the Wankhede Stadium later in the afternoon. "It wasn't an easy one to negotiate," Gower said. "We were advised to carry on as scheduled, and that's the advice I passed on as captain."

"Had the decision been left to the team, or more particularly to a majority of the representatives of the British press, there is little doubt they would have taken the first available flight home," Wisden reported. "But as in Delhi, Brown retained his sense of perspective, took advice from all relevant bodies and decided the best course was to stay and play. The decision had its dangers, based as it was on an educated guess that there was no connection between the timing of the murder and the team's presence in Bombay."

| ||

Brown acted decisively and quickly, explaining that " a further delay would only have served to set the players further on edge".

While reports hinted that the players wanted to head home, Gower said that there was no dissenting over the decision. "It was generally accepted reasonably well by the players," he said, although Engel noted that there was an undercurrent among them that they were being asked "to take one risk too many".

"At various times, certain groups of players might have felt uncomfortable, but in truth, that was as much to do with homesickness as fear," Neil Foster countered.

Writing eight years later, Engel, who accompanied the England team throughout, still maintained the tour should have been called off. "The team's safety was not beyond reasonable doubt," he said.

Marks was clear that most wanted out. "We felt vulnerable and the sudden emergence of special branch officers armed with Sten guns on the team bus was insufficient to allay our fears."

In the event, Brown was proved right, as Marks acknowledged. "With hindsight, staying on in India was a good decision."

The rest of the tour passed relatively peacefully, although security was intense. Some questioned quite how efficient it was, however. The night before the match some of the media suspected that assurances about the levels of security might be slightly exaggerated. They decided to put it to the test. The next morning one of the photographers presented himself to a senior guard at the ground in a flak jacket ("wearing the most scrambled egg of anyone" he told Cricinfo). He had his camera bag over his shoulder and a camera lens "that could have been a bazooka". When challenged he replied: "I'm from the IRA. Take me to the England dressing room." "Certainly," said the guard, "do come this way, sir."

Is there an incident from the past you would like to know more about? Email rewind@cricinfo.com with your comments and suggestions.

Bibliography

More Than A Game by John Major (Harper Collins 2007)

More Than A Game by John Major (Harper Collins 2007)