A prince among batsmen

Over a century ago, the English game was transformed by an Indian who went on to become the most popular cricketer in the Empire

Gideon Haigh

24-Aug-2009

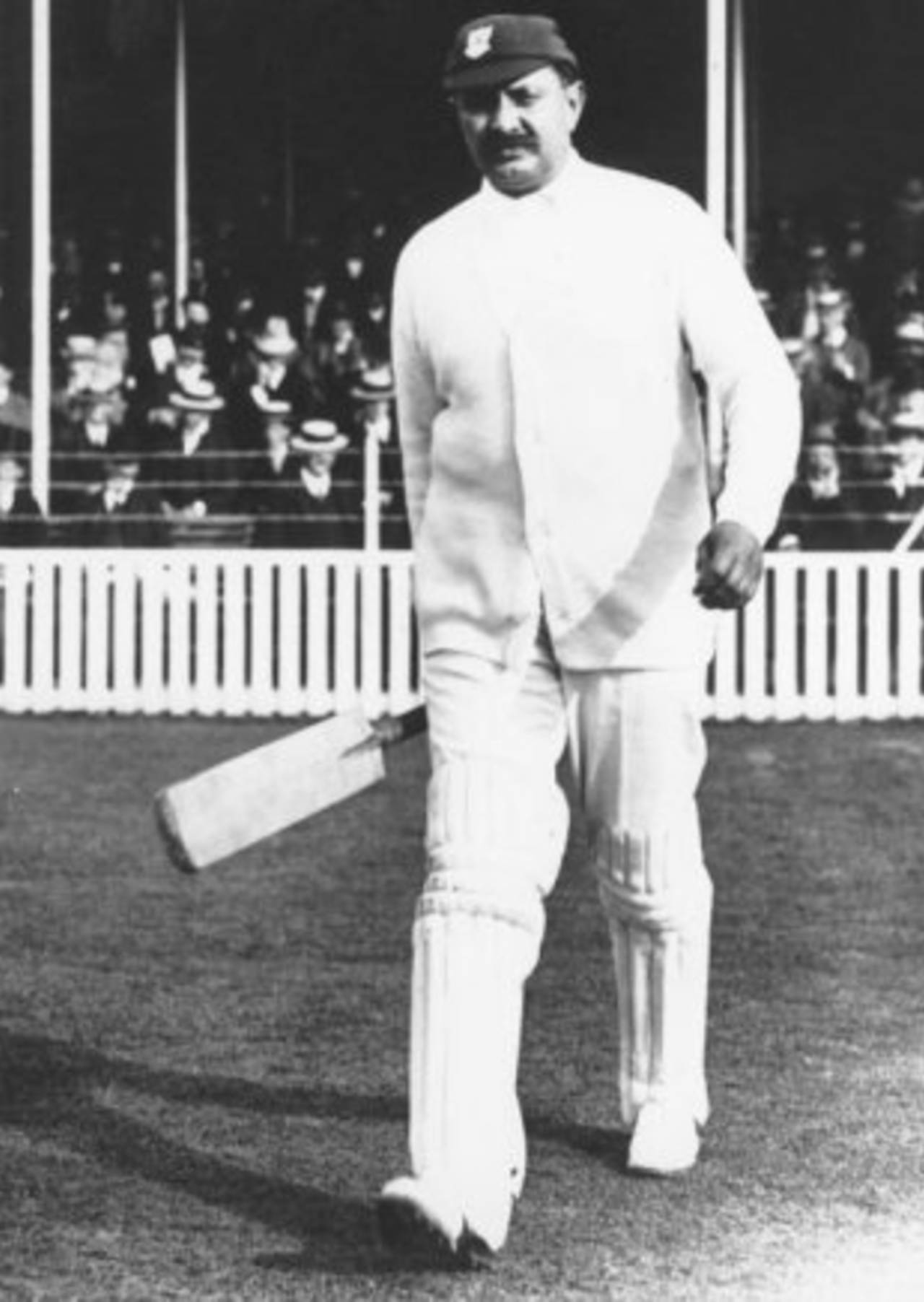

The "prince of cricket", though he was only briefly a prince in real life • Getty Images

Perhaps no cricketer in history has been as romanticised and sentimentalised as Ranjitsinhji. It testifies to his uniqueness that this romance and sentimentality do not significantly enlarge on reality. WG Grace prophesied that there would not be a batsman like Ranji for a hundred years. This is inherently untestable, but it did set a remarkably high standard.

Ranji was not only the first well-known Indian cricketer, but "the first Indian of any kind to become universally known and popular" - as John Lord puts it in The Maharajahs. And this through a concatenation of circumstances that has inspired not only four biographies but two novels: Ian Buruma's Playing the Game and John Masters' The Ravi Lancers.

There was, of course, always a mythic element to "Prince Ranji". He was, most importantly, only fleetingly a real prince, adopted as heir to the Jam Saheb of Nawanagar as a precaution against that ruler's inability to father an heir of his own. Ranji's princely status was revoked when an heir appeared four years later, and was not restored for the next quarter of a century. In fact, this caprice was integral to Ranji's first exposure to cricket. Apprehension about court intrigues in Jamnagar resulted in him enrolling 80km away at Rajkot's Rajkumar College, the "Indian Eton", where he developed as a promising all-round athlete before leaving for England in March 1888 to further his education.

Simon Wilde, one of Ranji's biographers, suggests that this disinheritance explains Ranji's determination at Cambridge to "make himself the prince of cricket". The unique batting style that seemed to flow directly from Ranji's exotic origins belied his self-mastering dedication and the valuable tutelage of Surrey professionals who came to coach undergraduates. Ranji reputedly tackled them in relays. "I must practise endurance," he told FS Jackson. "I find it difficult to go on after 30 minutes."

The legend is that one of these professionals nailed Ranji's back boot to the crease to cure the young Indian's tendency to retreat from the ball. True or not, the facility that Ranji subsequently developed for deflecting balls to leg changed the course of batsmanship forever, opening it up to previously unexplored run-scoring quadrants of the field.

Cricket, hitherto, had been an off-side game. Ranji's great friend CB Fry was told as a schoolboy: "If one hit the ball in an unexpected direction on the on side, intentionally or otherwise, one apologised to the bowler… The opposing captain never, by any chance, put a fieldsman there; he expected you to drive on the off side like a gentleman." Ranji's 1897 Jubilee Book of Cricket contained diagrams of 15 recommended fields for bowlers of various types: only one, for lob bowlers, contains more than three leg-side fielders and most feature only one or two. Ironically Ranji, more than any other batsman, rendered such formations obsolete.

Ranji's harnessing of the pace of the ball in the power of the stroke was also revelatory. As Gerald Brodribb contended in Next Man In, it "suggested a completely new way of getting runs". With wrist, eye and timing, batting became a discipline of touch and subtlety as much as of strength and force.

His disinheritance at Nawanagar explains Ranji's determination at Cambridge to "make himself the prince of cricket". The unique batting style that seemed to flow directly from Ranji's exotic origins belied his self-mastering dedication and the valuable tutelage

And not even a modern batsman would be as bold as Ranji, if Fry's description of his contemporary's "forward-glance-to-leg" is anything to go by. "The peculiarity," Fry wrote in Batsmanship, "was that he did more than advance his left foot at the ball… he advanced it well clear of the line of the ball to the right of it, and he somehow got his bat to the left of his left leg in line with the ball, and finished the stroke with a supple turn at the waist and an extraordinarily supple follow-through of wrist-work."

How Ranji's colour hampered his advance is difficult to ascertain. There was prejudice at Trinity College against "a nigger showing us how to play cricket", and Sir Home Gordon revealed in Background of Cricket that Ranji's signature habit of buttoning his sleeves to the wrist was "acquired at Cambridge to mitigate his dusky appearance".

Gordon also recalls that Ranji's selection for the 1896 Ashes series was debated at Lord's despite his stupendous Old Trafford debut, when he made 62 and 154 not out. "Old gentlemen waxing plethoric declared that if England could not win without resorting to the assistance of coloured individuals of Asiatic extraction, it had better devote its skill to marbles. Feelings grew so acrimonious as to sever lifelong friendships… one veteran told me that if it were possible he would have me expelled from MCC for having 'the disgusting degeneracy to praise a dirty black'."

Yet it is remarkable, as Alan Ross commented in Ranji, how quickly he "became a character". By the end of Ranji's debut series, the ramparts of Victorian England had yielded to him utterly. "At the present time," judged the Strand, "it would be difficult to discover a more popular player throughout the length and breadth of the Empire." And his fame would only grow: he published a string of books, was the subject of a biography by Percy Cross Standing, and a painting by Henry Tuke, and appeared in James Joyce's Finnegan's Wake as "ringeysingey".

With his leg-glance Ranji changed cricket from a predominantly off-side game•ESPNcricinfo Ltd

The time was ripe for a crowd-pleaser of Ranji's kind. With county cricket blossoming, he made the most of the expanding first-class programme: between 1898 and 1901 he and Fry, a combination unmatched in glamour, amassed 16,500 runs for Sussex. Standing noted that visitors were disappointed at Ranji's indifference to cricket's history: "What's he to Fuller Pilch, or Fuller Pilch to him? Nothing. On the other hand, today's weather forecast is everything." Perhaps Ranji intuited that history was of little account, save for the history he might make himself.

In an era usually identified with imperialism and white supremacism, why was Ranji's passage relatively frictionless? David Cannadine, in his Ornamentalism: How The British Saw Their Empire, contends that rank, as much as race, was the key to imperial order: "India's was a hierarchy that became the more alluring because it seemed to represent an ordering of society… that was increasingly under threat in Britain."

Ranji, famous for his ostentatious regalia and improvident flourishes of wealth, might be seen as colluding in those fantasies of an imagined east. On one occasion, dining at Hyde Park Hotel, Sir Home Gordon was struck by the shabbiness of Ranji's suit, but noted that at a military tournament later in the evening Ranji took the salute in the royal box "resplendent in Oriental attire and ablaze with jewellery".

Appreciations of Ranji's batting, too, often come from a perspective of inferiority, even gratitude. "We had got into a groove," wrote the England batsman Tom Hayward in his 1907 primer Cricket, "out of which the daring of a revolutionary alone could move us. The Indian Prince has proven himself an innovator. He recognises no teaching, which is not progressive, and frankly he has tilted, by his play, at our stereotyped creations."

By this time Ranji had essentially renounced cricket, his political ambitions having borne fruit with the restoration of his inheritance after the death of the Jam Saheb in August 1906. But Neville Cardus' remark that "when Ranji passed out of cricket a wonder and a glory departed from the game forever" was hyperbolic. Cricket's inheritance from Ranjitsinhji is enduring.

Gideon Haigh is a cricket historian and writer. Some articles in the Movers and Shapers series, including this one, were first published in Wisden Asia Cricket magazine in 2002