Take a bow, BCCI

The Indian board's decision to acknowledge the efforts of former cricketers with cash rewards is a good and much-needed gesture

Aakash Chopra

14-May-2012

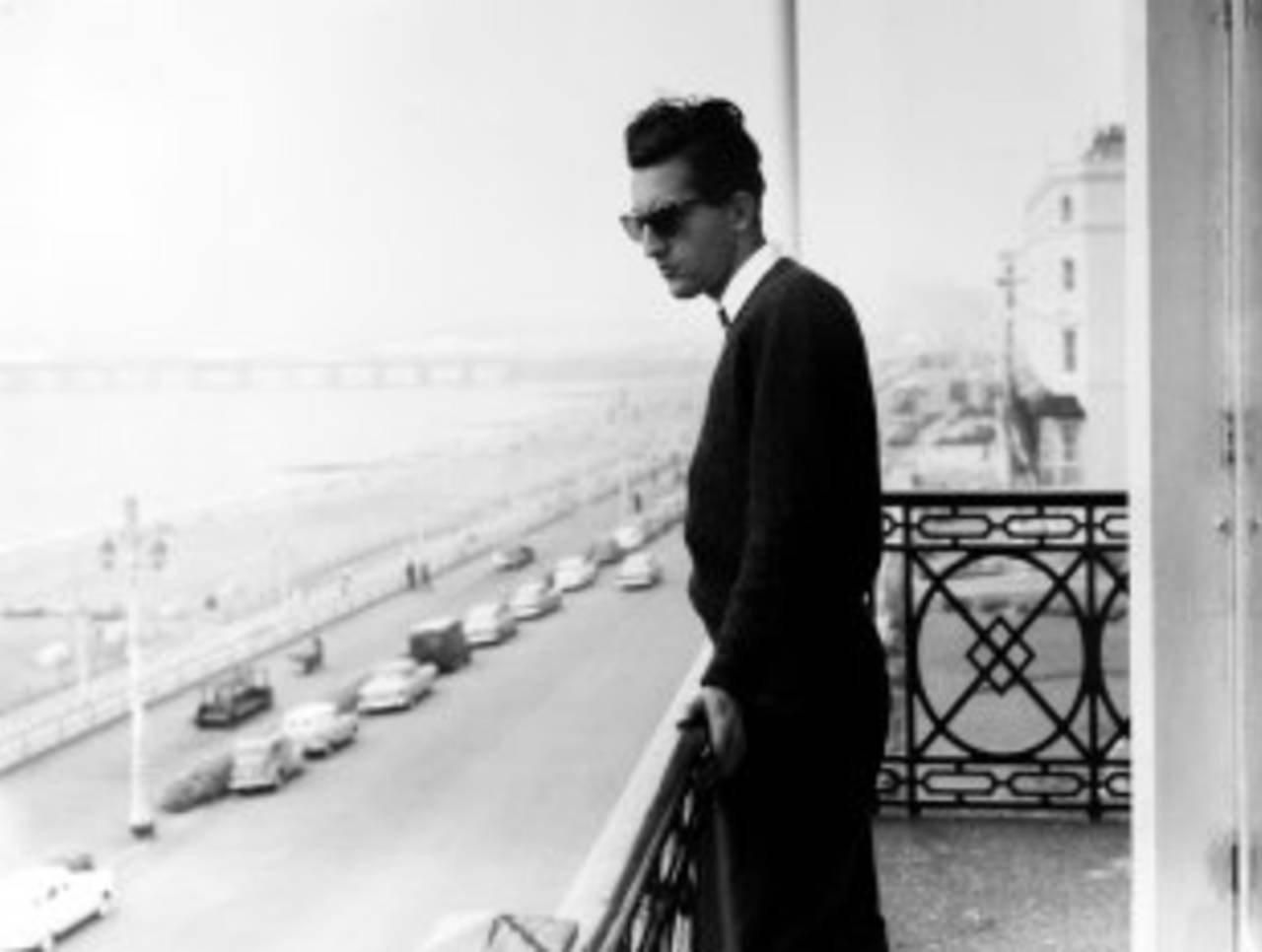

While players like Pataudi could afford to play the game without needing to depend on it financially, there have been several others who had no other source of income • Getty Images

The news that the BCCI has decided to dole out a large sum of money earned from IPL playoff games as rewards to ex-cricketers is wonderful.

Contrary to popular perception, cricket wasn't always rich in India. In the old days there was very little in the game by way of financial reward, and in fact, cricket asked a great deal in return from players. All the wealth that surrounds the sport today was unimaginable for cricketers who played in the 1960s, '70s and even '80s, which was when I first got into the game.

When I first picked up a bat as an ardent eight-year old, dressed in prim whites, a cap, shoes that had been bought after weeks of deliberation (and were preserved for nearly a decade), I was full of hopes and dreams. Cricket was perfect innocence; to think of playing it for hard cash was profane. One played only for the love of the sport, nothing else really. In any case, there was too little money in the game for it to be a lure.

During my club cricket days I remember waiting endlessly for the odd bus - perhaps the only one on the route that dared to venture out during the troubled times of the Mandal Commission. For the middle class in Delhi, buses were the only affordable form of public transport, auto-rickshaws being far too expensive. I remember clinging onto the rungs at the back of a public transport bus with a cricket kit bag weighing several kilos on my back. And sleeping on the floor of an overnight train alongside a team-mate to make it to a match in another city; the fact that there were rats, smelly shoes and filth all around did not matter enough to get us off the train or dampen our spirits. Life in those years was about spending time in the nets, hitting the ball well, scoring runs and doing all that it took to move to the next level. The lack of a few hundred bucks couldn't spoil the romance.

That's the thing about passion, struggle: you are so consumed with the thought of making it big one day that everything else seems trivial. That is pure, unadulterated love for the sport, really.

It was a different era. Many old-school romantics like me believed that while it was good to have money, and the things it could buy, it was also wise to keep intact the things money couldn't buy - like absolute love.

Nothing could be more wounding than the feeling that a life spent serving the game had been in vain

But yes, while money isn't everything, it hits you once the romance begins to fade that it is reasonably close to oxygen. Nothing can replace bread and butter on the breakfast table. How far did the Rs 400 we got for a three-day Under-19 game and Rs 1700 for a four-day Ranji Trophy game go?

Still, it wasn't bad enough for the likes of me to contemplate quitting the game to pursue other, more lucrative, career options. This was in the mid-90s; imagine the sort of passion the cricketers of the decades before that would have needed to give the game their best day in and day out, for perhaps Rs 100 or less a game.

Plenty of talented players fell by the wayside, while others were forced to forget loyalties and play as professionals for different state units, play exhibition matches, and also work full-time for banks or public sector companies. There were a few privileged ones like the Nawab of Pataudi, who graciously distributed his match fee amongst the team; most others were not half as fortunate - they just about managed to get by when they were playing but were hardly able to save anything for rainy days. When the sun went down on their careers, they were reduced to being the underprivileged cousins to their young, rich counterparts. The sport, the system, owed them something.

In 2004, the BCCI announced a pension scheme for players who played in the era before money transformed Indian cricket. In 2006, the scheme was extended to include Ranji Trophy cricketers. It was a noble gesture by the board to acknowledge the services of these players to Indian cricket. The mere fact of being remembered made these former cricketers feel a lot better about the time they spent playing the sport; nothing could be more wounding than the feeling that a life spent serving the game had been in vain.

The BCCI has now gone an extra yard and opened its coffers once again. "This is a small thank you to those who have done yeoman service to Indian cricket," said N Srinivasan while announcing the bounty. One can only guess at what this largesse will mean to cricketers who played decades for paltry payments. The money will ensure a steady flow of cash to foot medical bills, and go a long way towards securing their old age and the future of their families.

More than anything, this has been an acknowledgement of the unsung heroes who don't find a mention in the history books. Their game wasn't about surpassing competitors at any cost, but to serve the sport, in good times and bad.

Former India opener Aakash Chopra is the author of Out of the Blue, an account of Rajasthan's 2010-11 Ranji Trophy victory. His website is here and his Twitter feed here