We did overcome

Cricketers who got over physical or social obstacles to make a mark in the game

Steven Lynch

24-Oct-2011

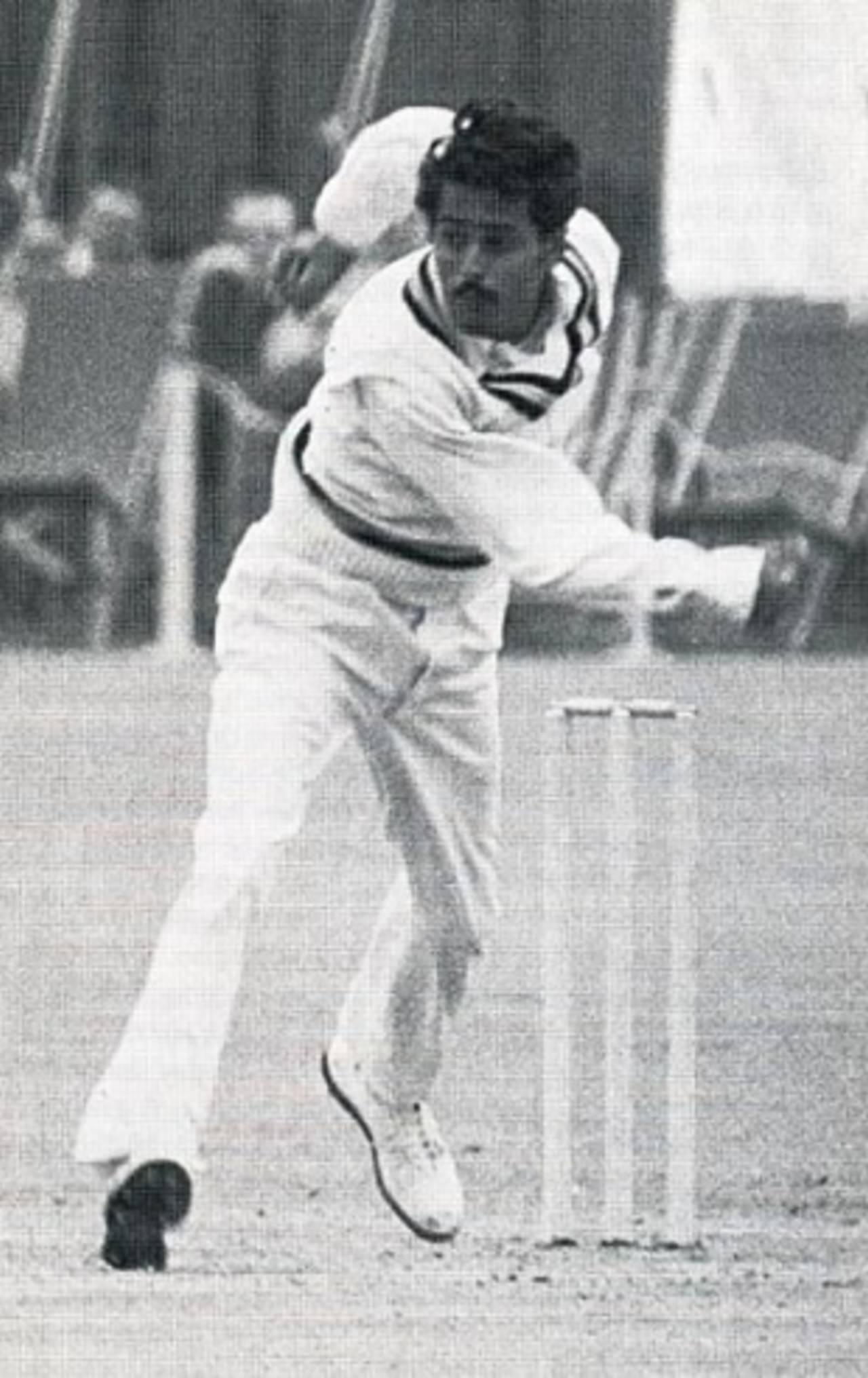

Bhagwath Chandrasekhar: created havoc with a weakened arm • Patrick Eager/The Cricketer International

Polio

Bhagwath Chandrasekhar suffered an attack of poliomyelitis as a child, which left his right arm withered: he always threw the ball in from the outfield left-handed. But his thin, whippy other arm was magical from 22 yards away from the batsman: he could send down a wonderful mixture of brisk bouncy legbreaks and top-spinners. Chandra was never more effective than at The Oval in 1971, when his 6 for 38 skittled England for 101 and helped set up India's first series victory in England.

Bhagwath Chandrasekhar suffered an attack of poliomyelitis as a child, which left his right arm withered: he always threw the ball in from the outfield left-handed. But his thin, whippy other arm was magical from 22 yards away from the batsman: he could send down a wonderful mixture of brisk bouncy legbreaks and top-spinners. Chandra was never more effective than at The Oval in 1971, when his 6 for 38 skittled England for 101 and helped set up India's first series victory in England.

Racial prejudice

Basil D'Oliveira was one of the leading batsmen in South Africa in the 1950s... but very few people knew that, as he was prevented from playing first-class cricket at home because of the colour of his skin. He eventually tried his luck in England, with great success, making his Test debut in 1966 and becoming a popular fixture in the team until 1972. But Dolly was almost 35 - possibly even older, as his date of birth has been the subject of much discussion - when he made his Test debut, and over 40 when he finished. Had he had a "normal" career, and started his international career when he was 25, who knows what he might have achieved.

Basil D'Oliveira was one of the leading batsmen in South Africa in the 1950s... but very few people knew that, as he was prevented from playing first-class cricket at home because of the colour of his skin. He eventually tried his luck in England, with great success, making his Test debut in 1966 and becoming a popular fixture in the team until 1972. But Dolly was almost 35 - possibly even older, as his date of birth has been the subject of much discussion - when he made his Test debut, and over 40 when he finished. Had he had a "normal" career, and started his international career when he was 25, who knows what he might have achieved.

Diabetes

Cricket history might have been very different if Allan Border had carried out his threat to resign after a dispiriting time in 1985-86 (he was persuaded to carry on, won the World Cup in 1987, and hardly looked back, eventually skippering in more than 90 Tests). Had Border stepped down, Australia's captain for the 1986-87 Ashes series would probably have been Dirk Wellham, who had made a century on his debut for New South Wales and added another on Test debut at The Oval in 1981. The bespectacled Wellham looked studious and quiet, but he was anything other than soft: diabetes required him to inject himself regularly with insulin, a practice that reduced some of the noisier elements of the Aussie dressing room to silence when they witnessed it. Wasim Akram was another high-profile sufferer of the disease.

Cricket history might have been very different if Allan Border had carried out his threat to resign after a dispiriting time in 1985-86 (he was persuaded to carry on, won the World Cup in 1987, and hardly looked back, eventually skippering in more than 90 Tests). Had Border stepped down, Australia's captain for the 1986-87 Ashes series would probably have been Dirk Wellham, who had made a century on his debut for New South Wales and added another on Test debut at The Oval in 1981. The bespectacled Wellham looked studious and quiet, but he was anything other than soft: diabetes required him to inject himself regularly with insulin, a practice that reduced some of the noisier elements of the Aussie dressing room to silence when they witnessed it. Wasim Akram was another high-profile sufferer of the disease.

Asymmetric arms

A wartime accident in the gym during commando training left Len Hutton with a broken left arm, which was badly reset and ended up an inch and a half shorter than the other one. This might have had a calamitous effect on the technique of a batsman who had already famously scored a Test triple-century - 364 against Australia at The Oval in 1938 - but Hutton adjusted well, making 14 more Test hundreds after the war, three of them doubles, and captained England to Ashes glory at home in 1953 and down under in 1954-55.

A wartime accident in the gym during commando training left Len Hutton with a broken left arm, which was badly reset and ended up an inch and a half shorter than the other one. This might have had a calamitous effect on the technique of a batsman who had already famously scored a Test triple-century - 364 against Australia at The Oval in 1938 - but Hutton adjusted well, making 14 more Test hundreds after the war, three of them doubles, and captained England to Ashes glory at home in 1953 and down under in 1954-55.

Epilepsy

Tony Greig had a successful Test career - and has had a long afterlife as an enthusiastic TV commentator - despite suffering from epilepsy. The English press knew about this, but agreed not to write about it - until Henry Blofeld "outed" him in a book about the Packer Affair. Greig confirmed in his autobiography that he had suffered occasional seizures when younger - but once he learned to recognise the signs that a fit might be imminent he was able to control the problem with medication.

Tony Greig had a successful Test career - and has had a long afterlife as an enthusiastic TV commentator - despite suffering from epilepsy. The English press knew about this, but agreed not to write about it - until Henry Blofeld "outed" him in a book about the Packer Affair. Greig confirmed in his autobiography that he had suffered occasional seizures when younger - but once he learned to recognise the signs that a fit might be imminent he was able to control the problem with medication.

Impaired vision (I)

Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi, who sadly died recently, was among the most brilliant of young batsmen: there are tales of him playing for Oxford University against mighty Yorkshire in 1960 and taming the county attack - Fred Trueman and all - to the extent that they did not know where to bowl at him. But the following year Pataudi was involved in a car accident that permanently affected his vision: for a while he saw two balls "and tried to hit the inside one". Eventually he opened his stance, pulled his cap down over the bad (right) eye, and continued to bat (and field superbly too). He managed to score a Test double-century despite all this - but he had been reduced to a very good player from a potentially great one.

Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi, who sadly died recently, was among the most brilliant of young batsmen: there are tales of him playing for Oxford University against mighty Yorkshire in 1960 and taming the county attack - Fred Trueman and all - to the extent that they did not know where to bowl at him. But the following year Pataudi was involved in a car accident that permanently affected his vision: for a while he saw two balls "and tried to hit the inside one". Eventually he opened his stance, pulled his cap down over the bad (right) eye, and continued to bat (and field superbly too). He managed to score a Test double-century despite all this - but he had been reduced to a very good player from a potentially great one.

Impaired vision (II)

Medium-pacer Eiulf "Buster" Nupen was a master on the matting wickets used in South Africa in the 1920s. Against England in 1930-31 he took 11 wickets in the first Test and nine in the fourth - but he didn't even play in the third and fifth Tests, the first to be played on turf pitches in South Africa. He was similarly ineffective on his only overseas tour, to England in 1924. But he remained a master on the mat, taking 184 wickets in 28 Currie Cup matches for Transvaal at an average of less than 13. He did all this despite having only one eye: he had lost the sight in the other one when he was four. Nupen, whose forebears were from Scandinavia, is the answer to a frequent quiz question about the "one-eyed Norwegian" who played Test cricket.

Medium-pacer Eiulf "Buster" Nupen was a master on the matting wickets used in South Africa in the 1920s. Against England in 1930-31 he took 11 wickets in the first Test and nine in the fourth - but he didn't even play in the third and fifth Tests, the first to be played on turf pitches in South Africa. He was similarly ineffective on his only overseas tour, to England in 1924. But he remained a master on the mat, taking 184 wickets in 28 Currie Cup matches for Transvaal at an average of less than 13. He did all this despite having only one eye: he had lost the sight in the other one when he was four. Nupen, whose forebears were from Scandinavia, is the answer to a frequent quiz question about the "one-eyed Norwegian" who played Test cricket.

Tuberculosis

Bob Appleyard, a nippy Yorkshire medium-pacer, made a sensational start in first-class cricket: after a couple of matches in 1950, he took 200 wickets in 1951, and was named as one of Wisden's Five Cricketers of the Year. But the following season he fell ill: what was initially thought to be pleurisy turned out to be the lung disease tuberculosis, which often proved fatal back then. Appleyard spent most of 1952 in a hospital bed and wasn't expected to recover enough to play cricket again - but he did, roaring back in 1954 with 154 wickets and making his Test debut (he took 5 for 51 against Pakistan). A shoulder injury cut his comeback short, but although Appleyard played only nine Tests, there are those who would include him in an all-time England XI.

Bob Appleyard, a nippy Yorkshire medium-pacer, made a sensational start in first-class cricket: after a couple of matches in 1950, he took 200 wickets in 1951, and was named as one of Wisden's Five Cricketers of the Year. But the following season he fell ill: what was initially thought to be pleurisy turned out to be the lung disease tuberculosis, which often proved fatal back then. Appleyard spent most of 1952 in a hospital bed and wasn't expected to recover enough to play cricket again - but he did, roaring back in 1954 with 154 wickets and making his Test debut (he took 5 for 51 against Pakistan). A shoulder injury cut his comeback short, but although Appleyard played only nine Tests, there are those who would include him in an all-time England XI.

Thilan Samaraweera returned to international cricket six months after being shot in the thigh during the attack on the Sri Lankan team bus in Lahore•AFP

A bullet

When the Sri Lankan team bus was ambushed by terrorists in Lahore early in 2009, several players were injured. The worst was batsman Thilan Samaraweera, who had a bullet lodged in his thigh. His career hung in the balance - all the more galling as he was in the form of his life, having scored 231 in the first Test against Pakistan, and 214 in the second one before the gunmen struck. But thankfully Samaraweera recovered, and less than six months later was making 159 and 143 in successive Tests against New Zealand.

When the Sri Lankan team bus was ambushed by terrorists in Lahore early in 2009, several players were injured. The worst was batsman Thilan Samaraweera, who had a bullet lodged in his thigh. His career hung in the balance - all the more galling as he was in the form of his life, having scored 231 in the first Test against Pakistan, and 214 in the second one before the gunmen struck. But thankfully Samaraweera recovered, and less than six months later was making 159 and 143 in successive Tests against New Zealand.

Missing fingers

The Australian slow left-armer Bert Ironmonger - nicknamed "Dainty" because he wasn't - had lost the top of his left forefinger in an accident on the family farm. But he turned this disability to his advantage, fizzing the ball off the remaining stump to obtain appreciable spin. When he was almost 50 he returned the astonishing figures of 11 for 24 - 5 for 6 and 6 for 18 - as South Africa were skittled for 36 and 45 on a sticky wicket in Melbourne in 1931-32.

The Australian slow left-armer Bert Ironmonger - nicknamed "Dainty" because he wasn't - had lost the top of his left forefinger in an accident on the family farm. But he turned this disability to his advantage, fizzing the ball off the remaining stump to obtain appreciable spin. When he was almost 50 he returned the astonishing figures of 11 for 24 - 5 for 6 and 6 for 18 - as South Africa were skittled for 36 and 45 on a sticky wicket in Melbourne in 1931-32.

Lost arm

Frank Chester was talked of as a Test prospect after he scored nearly 1000 runs for Worcestershire in 1914, when he was only 19. But during the Great War he received a severe injury to his right arm, which had to be amputated just below the elbow. Not even a brilliant young batsman could overcome that disability to play first-class cricket again - but Chester did the next-best thing, turning to umpiring and becoming the world's best in a white coat (and the best known until Dickie Bird came along). Chester stood in 48 Tests between 1924 and 1955, which remained a record until Bird surpassed it late in 1992.

Frank Chester was talked of as a Test prospect after he scored nearly 1000 runs for Worcestershire in 1914, when he was only 19. But during the Great War he received a severe injury to his right arm, which had to be amputated just below the elbow. Not even a brilliant young batsman could overcome that disability to play first-class cricket again - but Chester did the next-best thing, turning to umpiring and becoming the world's best in a white coat (and the best known until Dickie Bird came along). Chester stood in 48 Tests between 1924 and 1955, which remained a record until Bird surpassed it late in 1992.

Steven Lynch is the editor of the Wisden Guide to International Cricket 2011.