Man and superman

Off the field he may have been an awkward hero, on it Garry Sobers was "evolution's ultimate specimen"

Gideon Haigh

16-May-2009

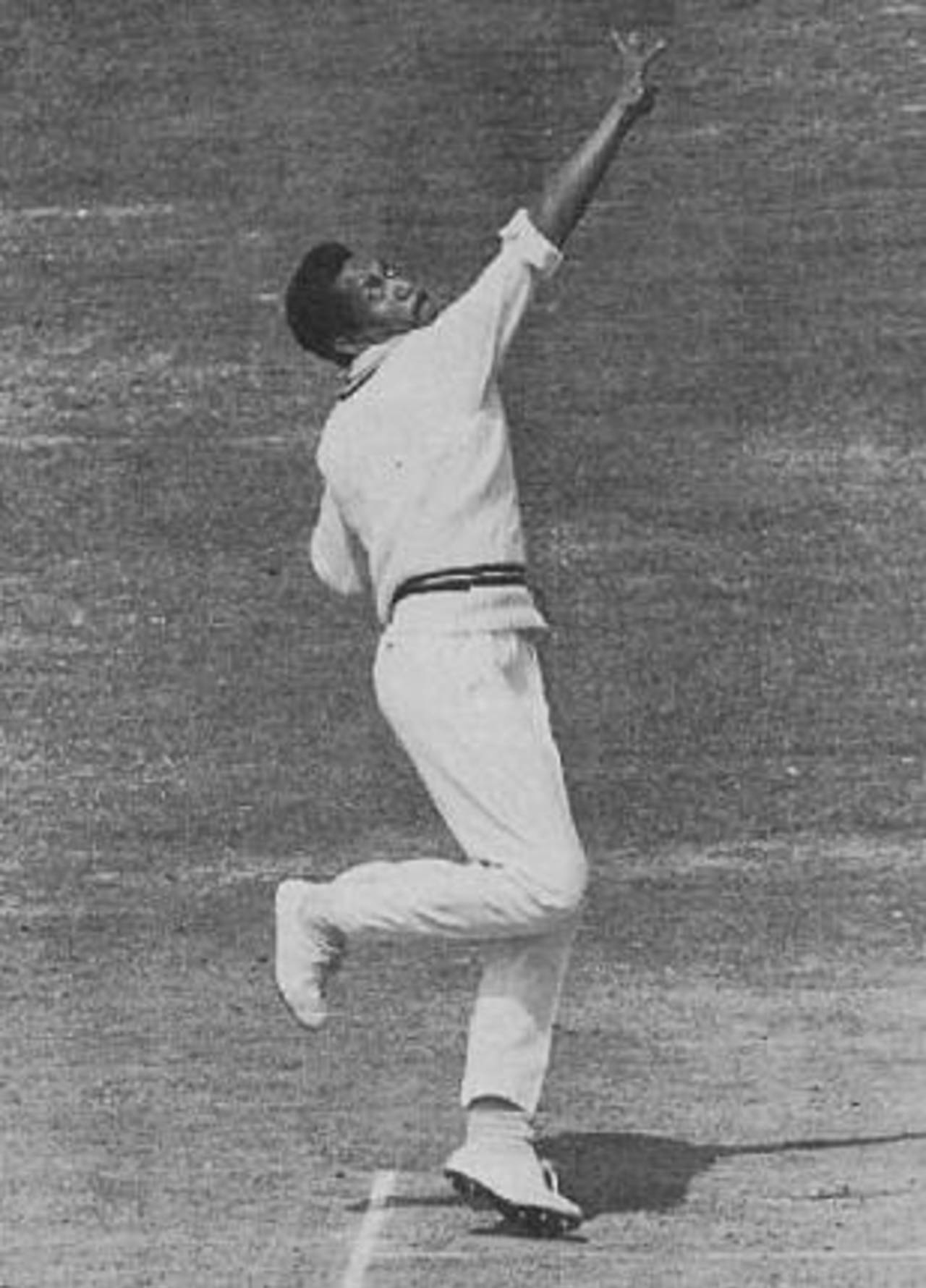

Sobers bowled every variety of left-arm delivery, batted from one to nine in the West Indies order, and fielded in every position with uniform excellence • The Cricketer International

In Cricket In The Leagues, John Kay describes a match in which Garry Sobers represented Norton and was hit back over his head. Sobers reportedly turned, ran towards the boundary shouting "leave it to me" and took the catch just in front of the sightscreen.

"Leave it to me" - and you could. To Ray Robinson, Sobers was "evolution's ultimate specimen in cricketers". He combined faculties of the game as no other, batting from one to nine in the West Indies order, bowling every variety of left-arm delivery, fielding in every position with uniform excellence and captaining with a knowledge that his predecessor Frank Worrell described as encompassing "everything" - this for two decades, with only the barest attenuation in performance as age encroached. Incorporate Sobers' matches leading world XIs and his international record stretches from horizon to horizon: almost 9000 runs at 58, 265 wickets at 33, and 121 catches.

All this was accomplished, furthermore, with a unique elasticity and elan. Of his batting Barry Richards once observed that Sobers was "the only 360-degree player in the game"; that is, his follow-through ended where his pick-up began, swinging "right through every degree on the compass". The generosity of swing was matched by a generosity of spirit, for Sobers was also a walker throughout his career - not only a mark of sportsmanship but indicative of a confidence in his abilities that needed no help from luck. And one notes of his bowling that, despite operating under front- and back-foot laws, he bowled only a handful of no-balls in his entire career. Such was his instinctive feeling for cricket's calibrations.

In the post-colonial West Indies, not surprisingly, Sobers was a point of pride, almost a divine. CLR James - and none wrote better of Sobers than James - saw in him "the living embodiment of centuries of tortured history", and "a West Indian cricketer, not merely a cricketer from the West Indies".

The appointment of Worrell to lead West Indies to Australia in 1960-61 is generally regarded as the defining moment in Caribbean cricket. But, as Brian Stoddart suggests in Liberation Cricket: West Indies Cricket Culture, Sobers' succession, taken on the field in March 1965, was "the real break with the past". Worrell was courtly, tactful, educated at an English university, a Freemason; Sobers' background was both indigenous and indigent. He was raised by a widow in a small shack in Bridgetown's Bay Land, a tenantry created for plantation workers after the cessation of slavery in 1838. Between docks that were a crucible of industrial dispute and a local cricket club for whites only. His rise from exclusion to eminence, Hilary Beckles contends in The Development of West Indies Cricket, sent "a signal of hope for collective redemption".

In some senses, however, Sobers was an awkward hero in the cause of West Indian self-affirmation through sport. He did not view defeat in a Test as setting back the struggle for national prestige: "Cricketers are entertainers", he said, when he scandalised fellow countrymen with his costly declaration in Trinidad in 1967-68.

He was awkwardly apolitical too. He explained his controversial visit to Rhodesia for a double-wicket competition in September 1970 by saying he "knew nothing of politics at the time". His avowal that "there should be no barriers in sport" smacked of an apology for sporting contact with South Africa. (Sobers, in fact, makes clear in The Changing Face of Cricket that he did not play in South Africa himself only because he had "had my fill of publicity and criticism" during the Rhodesian affair; it had "nothing to do with what was happening in the country".)

He was raised by a widow in a small shack in Bridgetown's Bay Land, a tenantry created for plantation workers after the cessation of slavery in 1838. Between docks that were a crucible of industrial dispute and a local cricket club for whites only. His rise from exclusion to eminence sent a signal of hope for collective redemption

He was as slow to militancy as some of his successors were quick. It is interesting, for example, to contrast Sobers' and Viv Richards' responses to Tony Greig's vow to make the 1976 West Indians "grovel". In Hitting Across The Line, Richards recalls it as a "racist dig", which "gave strength to a lot of the West Indian guys". In Twenty Years At The Top, Sobers dismisses it as a throwaway line.

On the face of it, then, there is a tension here. Sobers was, for many fellow countrymen, a cultural embodiment. Yet he could appear remote, removed from dimensions of that culture. Why? It may be instructive to consider one of the most intriguing events in West Indian cricket history - or, to be precise, non-events, for ultimately it did not happen.

After his first few years in Test cricket Sobers followed the well-trodden route of many West Indians into the English leagues, representing Radcliffe in the Central Lancashire League from 1958 to 1962. After his feats in 1960-61 he was also lured to South Australia for three seasons, inspiring their first Sheffield Shield win in a decade. "My kind of cricket is world cricket," he explained breezily in Cricket Crusader. "And the jet plane makes all-year-round cricket possible for the individual world player."

It was as an "individual world player" representing South Australia that, in early 1963, the invitation from the West Indies board to tour England found him. The tour fee, a derisory £800, irked Sobers: he could earn far more in a summer of one-day-a-week league cricket. He equivocated, discussing the tour with Donald Bradman and Richie Benaud. Both urged him to go, although Bradman agreed that "with your standing you should get more money than anyone in the game", and Sobers remained ambivalent. What finally persuaded him was a strongly worded letter from Worrell reminding him of his patriotic duty.

Many sportsmen of that period struggled to reconcile the prestige of international sport with its paltry rewards. But Sobers' position was more complex than that of, say, an Australian tennis player choosing between the patriotic tug of the Davis Cup and the enticements of the professional circuit. Cricket was at the heart of West Indian cultural identity, more than a game, more than a job. Its devotees were unready for an "individual world player" who decoupled sport and politics.

CLR James: Sobers was a West Indian cricketer, not merely a cricketer from the West Indies•Getty Images

None of which is to say that Sobers should have rejected Worrell's overtures; one rejoices that he did not, for his 322 runs and 20 wickets were decisive in one of Test cricket's greatest series. Nor is it to say that Sobers went altogether unrewarded. When England admitted overseas professionals in 1968, Sobers was comfortably the best paid on £5,000 a season. He says himself in Changing Face that he "lived well in my 20 years in the game", even if "my mind boggles at the earnings of today's players".

But there was a paradox in his position. In participating in the emancipation of West Indian cricket, the outstanding cricketer of his generation had to consent to his own continued economic exploitation. To optimise his rewards his only recourse was to play virtually without interruption: in Test, first-class, league and one-day cricket he batted almost 900 times for nearly 40,000 runs and bowled more than 92,000 deliveries for close to 2,000 wickets.

Sobers' experiences account for his rallying to the cause of Kerry Packer's World Series Cricket in 1977 "because I wanted to see the leading players earn more money from the game". He oversaw the toss in the first Super Test, lent his name to the Sir Garfield Sobers Trophy and acted as a Packer ambassador. It also explains his reluctance to criticise the West Indian rebel tours of South Africa in 1983-85. Sobers felt a sympatico with players "who saw an opportunity to put themselves on a more financially viable footing".

In what one might call the Jamesian chain of cricket heroes - linking Learie Constantine, George Headley, Worrell, Sobers and Richards - Sobers is an unusual presence, one who did all things on the cricket field with ease, but who encountered the difficulty off it of having to be all things to all men.

Gideon Haigh is a cricket historian and writer. Some articles in the Movers and Shapers series, including this one, on cricket's most influential players, were first published in Wisden Asia Cricket magazine in 2002