Make captains allies in the fight against corruption

Administrators must be prepared to allow fixers back into the fold, provided they are ready to be held up as examples of what not to do

Ian Chappell

Mar 25, 2012, 2:31 AM

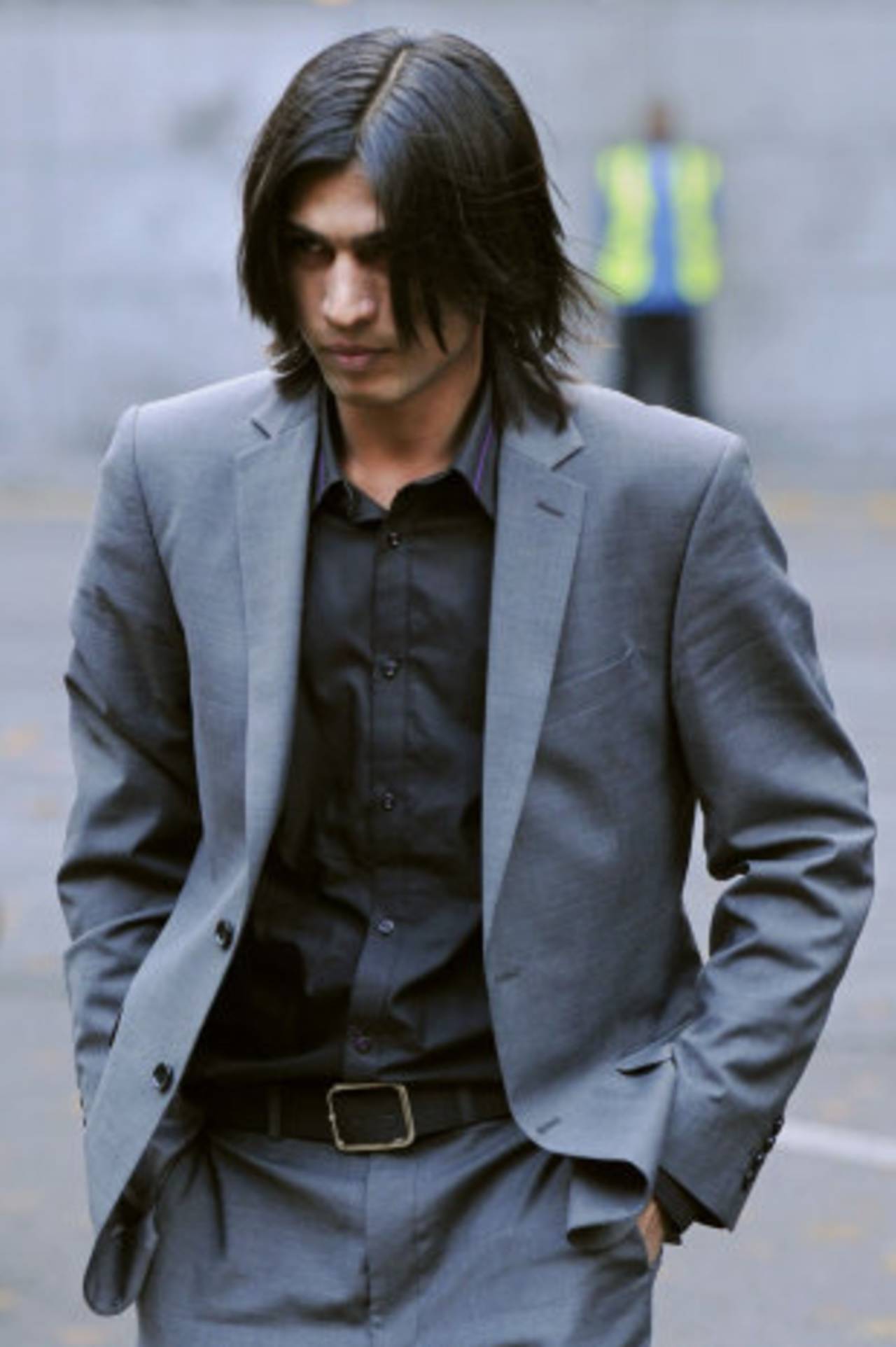

The public may feel sympathy for Mohammad Amir but cricket administrators can't afford to do the same • AFP

Life bans are imperative for any player or official involved in fixing - no questions asked. That's because fixing is the one vice that could bring cricket to its knees.

There has been a lot of sympathy for Mohammad Amir, the young Pakistan fast bowler who has just been released after serving half of his six-month custodial sentence. The sympathy is not surprising; he's still a teenager and he's also an extremely talented cricketer, but as Imran Khan observed when Amir was charged: "At 18 you're old enough to know right from wrong."

It's fine for the public to express their sympathy, but in such a high-stakes battle, cricket's officials can't afford any similar emotions. With one exception (discussed below), Amir and all other convicted fixers must be handed life bans from the game and not be able to hold an official position in cricket thereafter.

The crooks certainly don't have any sympathy for cricket. They have displayed an utter disregard for the game and have targeted international captains, the men charged with the authority and duty of influencing young players under their command. Until fixing reared its ugly head it was generally assumed a captain's influence would be positive, or at least not negative.

The fact that four prominent international captains, Mohammad Azharuddin, Saleem Malik, Salman Butt and the late Hansie Cronje, have in the past been found guilty of fixing offences is a worrying trend. It could also confirm the suspicion that to enact a major fixing scam the captain has to be involved.

In order to build a barricade around the game the administrators need to explore ways to ensure team captains are allies in the fight against fixing rather than some being tempted to side with the crooks. And despite employing a zero-tolerance policy the officials should be prepared to make exceptions and invite convicted fixers back into the fold on one condition. If the wrongdoers are truly repentant and prepared to stand up publicly and admit their guilt and speak about the humbling experience, then they could be employed to tell their story to young cricketers to dissuade them from taking the road to self-destruction. It would be a sort of cricketing equivalent of the justice system's hours of community service. When he's ready for the ordeal, this could be a task for a player like Amir.

Cricket is in a life-or-death struggle with the crooks who run the fixing scams. At the moment the bout is lopsided; one contestant is following Marquess of Queensberry rules and the other is a bare-knuckle streetfighter who does not acknowledge any restrictions.

The administrators should inform their anti-corruption officers that in addition to following phone and financial records aggressively, they shouldn't be afraid to rattle the cages of players who they think are acting suspiciously. They should think of it like a cricket match - if you're up against a tough opponent and don't do something to provoke a mistake from the opposition, you're going to lose.

While officials have to be extremely tough in the punishment they mete out in order to send a strong message to the crooks, they also have to make the players fully aware that they intend to eradicate fixing.

It's hard not to feel sympathy for Amir and anger towards Butt, but the administrators can't afford that luxury - for them it has to be a one-size-fits-all situation. However, it's difficult to have any sympathy for the officials - if they had taken notice of some recommendations in the 1999 Qayyum Report, then they might not have had so many problems with the Pakistan team.

Former Australia captain Ian Chappell is now a cricket commentator and columnist