The sickening thrill of the late collapse

Remembering two electric periods of play when Malcolm Marshall and Michael Holding ripped India to shreds

Samir Chopra

Apr 25, 2013, 7:13 AM

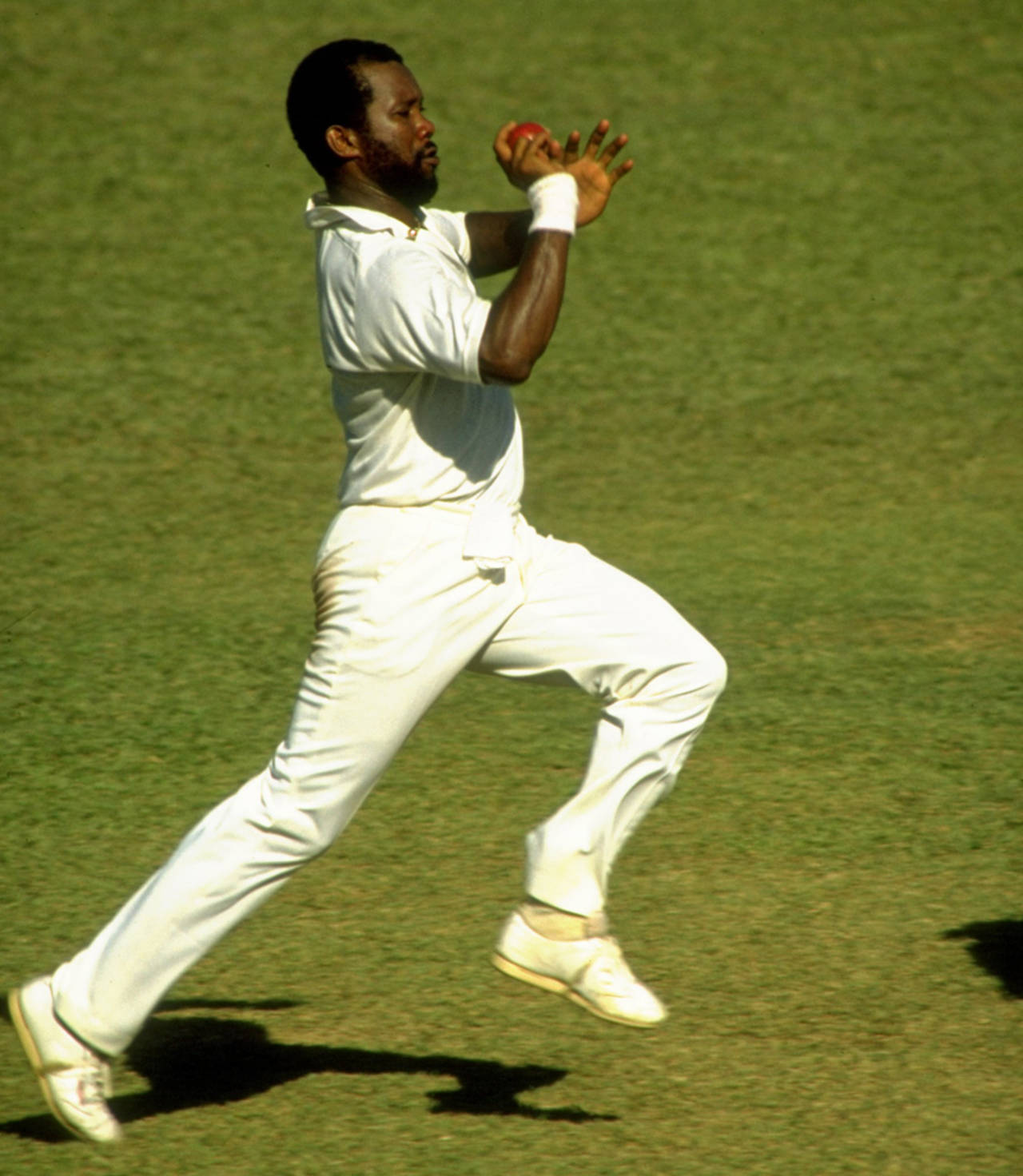

Marshall law in Kanpur • Ben Radford/Getty Images

A couple of years ago, in a post titled Little beginnings, I wrote about crucial, brief sessions of play where the batting side, coming out to play late in the day, had attempted to seize the initiative from the bowling side. I wrote about these in the context of passages of play in Test cricket:

Some opening passages of play are well established as mood-setting tropes: the opening batsmen's encounter with the new ball on the first day, the commencement of the fourth-innings chase, or the second-innings response to a large first-innings total.

Among these kinds of openings of an innings is a classic period of play: the little beginning, late in the day, when opening batsmen come out to play out a few overs before shutting up shop again for the day after. At that moment, the batting side has everything to lose, the bowling side has everything to gain (the list of small but dramatic collapses late in the day, achieved within a few overs, is quite long). The fast bowlers can go flat out, the fielders are keen and haring about, the light is starting to get dodgy. The batting side's fans hang on tight, hoping to make it through unscathed.

Today, I want to point to two such dramatic periods of late-in-the-day play that showcased astonishing collapses, where the batting side did not make it through unscathed. In each case, the bowling side was champing at the bit, and the batting team, well aware that they had let their opponents off the hook earlier, when it had been their turn to bowl, might well have been excused for being apprehensive about what lay in store.

Both the sessions of play I have in mind occurred in the same series: during West Indies' 1983-84 tour of India. The first occurred in India's first innings in the first Test in Kanpur, and the second in India's second innings in Calcutta. India lost both Tests by an innings, and in both cases these little passages of play dealt their batting a blow from which they could not, and did not, recover.

First to Kanpur. In West Indies' first innings, India had had their chances, having reduced the mighty tourists to 157 for 5 at one stage. But Gordon Greenidge, en route to a monumental 194 that took over nine hours, put on partnerships of 152 and 130 with Jeff Dujon and Malcolm Marshall, to guide West Indies to 454. Unfortunately for India the last man out was Marshall, cruelly denied his maiden Test century as he fell for 92.

Indian cricket fans had seen a young Marshall make his debut as part of Alvin Kallicharran's weakened side on their 1978 tour of India; they had heard of his maturing over the years; they had seen him bowl against India in the 1983 World Cup final. They had, however, not seen him bowl the way he would in this series.

In two balls, he made his mark, dismissing Sunil Gavaskar, caught behind for a duck. India 0 for 1. A few deliveries later, Mohinder Amarnath, about to begin his infamous "binary" run of scores, was leg-before for a duck. India 0 for 2. Both batsmen had looked flat-footed against the whippy Marshall. Then Gaekwad, poking desperately, edged one to Dujon and left, perhaps relieved to be out of the firing line. India 9 for 3.

If the sight of India's top batting stars being dismissed for ducks, and three wickets down before the total was in double figures, had not been enough to stun the crowd into silence, Marshall's wicket of Dilip Vengsarkar, whose stumps were thrown into disarray, most assuredly did. India 18 for 4.

The ducks were not done for the day; Winston Davis, happy to wade into the carnage Marshall had engendered, snapped up Ravi Shastri for a blob. India 29 for 5.

India ended the day at 34 for 5, with Marshall's bowling figures reading 8-5-9-4. Cue the most famous headline in modern Indian cricket history: "Marshall Law in Kanpur". It captured the sense of that late evening perfectly: the Indian batsmen, pinned to the crease, prisoners of a suffocating, hostile spell of pace bowling, before which all resistance was futile.

Marshall would only bowl another seven overs the next day, and not take any more wickets, to finish with 15-7-19-4. But the damage had been done. India were only able to recover partially before subsiding to 207 all out.

Incredibly enough, following on, India would again lose their first five wickets under 50, three of them to Marshall, and they went on to lose by an innings and 83 runs. (This little spell of play featured a moment familiar to all Indian fans who watched the telecast: Gavaskar's bat knocked out of his hand by a Marshall scorcher.)

Later in the series, India travelled to Calcutta 0-2 down, and like in Kanpur, managed to manoeuvre themselves into a position of possible strength. Early on the third day, despite being bowled out for 241 in the first innings (including a Gavaskar first-ball-of-the-Test duck to Marshall), India had managed to take the first eight West Indian wickets for 213. The door was ajar.

Unfortunately for India, one of the batsmen still undefeated was West Indian captain Clive Lloyd, who had carried out a successful transformation from a 1970s swashbuckler to a 1980s blocker. Still capable of attacking when the occasion called for it, Lloyd was now also a master of the defensive innings. With Andy Roberts, he proceeded to put on 161 for the ninth wicket, and broke India's will in the process.

When the Indian second innings finally began, light was fading at Eden Gardens. Less than an hour's play would be possible, and perhaps India could escape, perhaps they could claw their way back into the game. As India crossed double figures, some fans might have dared to dream more ambitiously. But not for too long.

This time the destroyer was Michael Holding. First to go was Gaekwad, cleaned up comprehensively. India 14 for 1. Gavaskar, sensing trouble, had been playing his strokes, perhaps hoping to replicate his heroics in Delhi, where he had belted a dramatic century off the same attack in the second Test. This time, though, he was out ingloriously, slashing at a wide one and caught behind (and earning himself the unjust jeering of those who thought he had been unduly reckless.) India 29 for 2.

Almost immediately Vengsarkar was trapped leg-before by Marshall. India 29 for 3. But it was the fourth wicket that finally completed that day's gloom. Amarnath had walked out on the back of a string of scores that read 0, 0, 0, 1, 0. A few balls later, he had his fifth duck of the series. To this day, I have not seen a more spectacular instance of a batsman being bowled: both his off and middle stump were sent flying - the off stump cartwheeling toward slips, the middle toward the keeper.

By now, I was used to West Indian fast bowlers dominating Indian batsmen. But this dismissal, this contemptuous removal of a man who had stood up to their might again and again, was the last straw. The sense of threat in the air was palpable; the West Indians looked and felt merciless. The light was poor, rounding out the doom and despondency that now infected Indian spirits. The game was up.

Sure, a fifth wicket for the day, a rest day, and the Indian lower order still had to be reckoned with, but in any real cricketing sense the game was up the moment Amarnath's stumps did their crazy little pirouette.

I have seen many collapses in Test cricket triggered by fast bowlers. But those two, perhaps because of their placement late in the day, perhaps because of the quality of bowling on display, have always stood as the most stellar examples of how an inspired fast-bowling unit can suddenly and irrevocably swing a game their team's way.

Samir Chopra lives in Brooklyn and teaches Philosophy at the City University of New York. He tweets here