Test cricket was just over 50 years old when West Indies joined the club of England, Australia and South Africa in 1928. The dominant view about the colonised West Indians held them to be primitives who might be expected to take the field barefoot and in sparse clothing. The Boy's Own Paper remarked on the "great novelty of the presence of coloured men playing on a cricket field in England". Certainly, they were seen as novices come to learn at the feet of the cricket masters.

By the end of that tour,

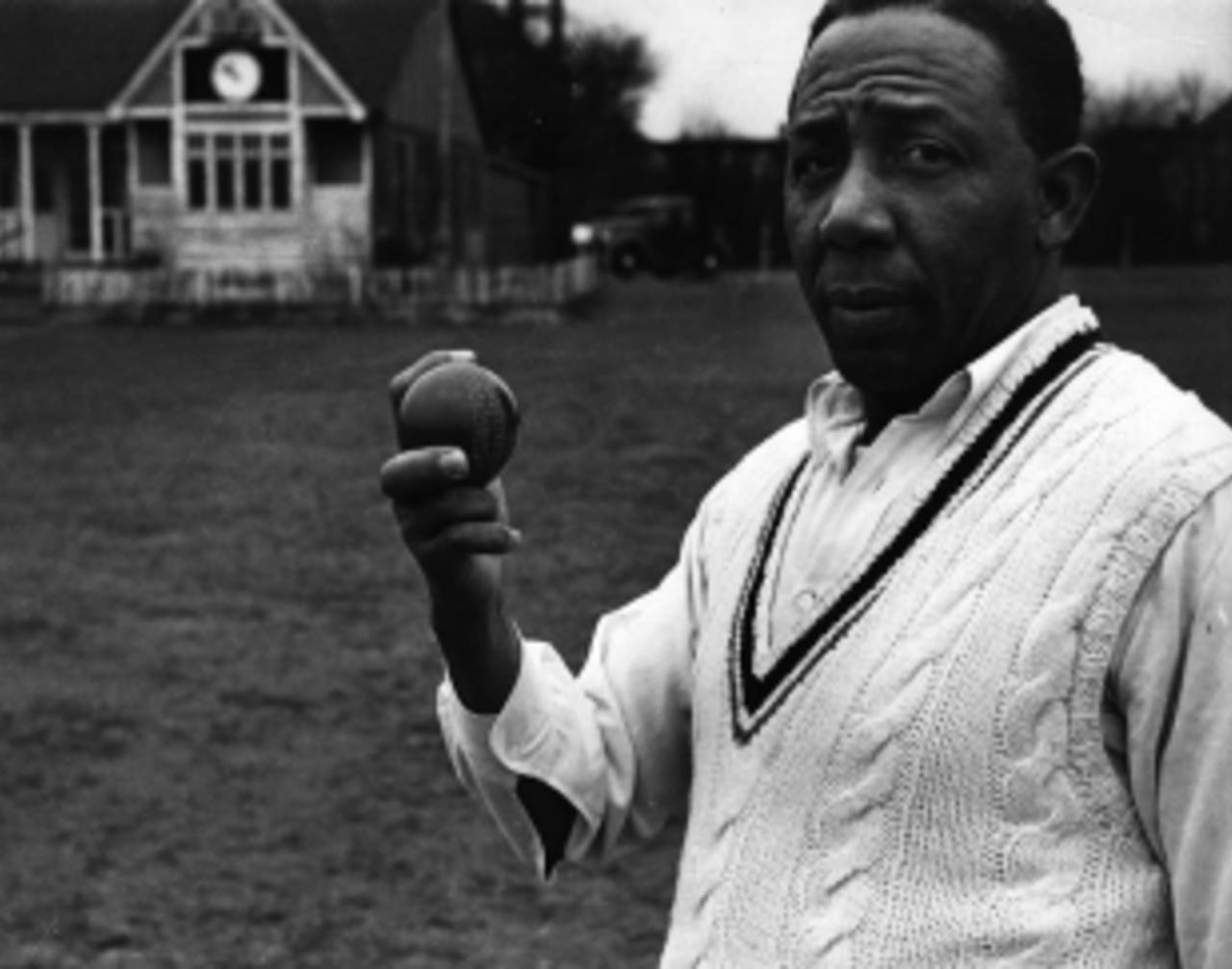

Learie Constantine, a black man, had challenged those views with the outstanding quality of his cricket in every department. His spectacular fielding, batting and bowling earned him superlative tributes in the press, and resulted in a contract to play for Nelson Cricket Club in the Lancashire league.

Then came

George Headley, another extraordinary batsman, whose class was compared to Don Bradman's. Together these two forced the cricketing elite to reconsider its view about the ability of black cricketers.

Constantine, a close friend of CLR James, had developed views about equality amongst men. He campaigned vigorously for recognition of their rights, both internationally and at home in the West Indies, where the selection process favoured white colonists, regardless of talent.

Headley, though not as vocal as Constantine, spoke with his bat and was visibly aligned to the cause. Both took stances that helped improve working and financial conditions for players. Through them, the cricket world became sensitive to such issues, and in the West Indies, where volumes of debate were ignited, recalcitrant selectors were pushed onto the path of meritocracy. Headley was appointed captain of the West Indies team in 1948; it came late but it was a step that broke a tradition, and it signalled the beginning of a different kind of representation for cricketers.