The American who became a cricket writer

Mike Marqusee wrote on many subjects but particularly insightfully and searchingly on our game

Rob Steen

Jan 15, 2015, 11:55 AM

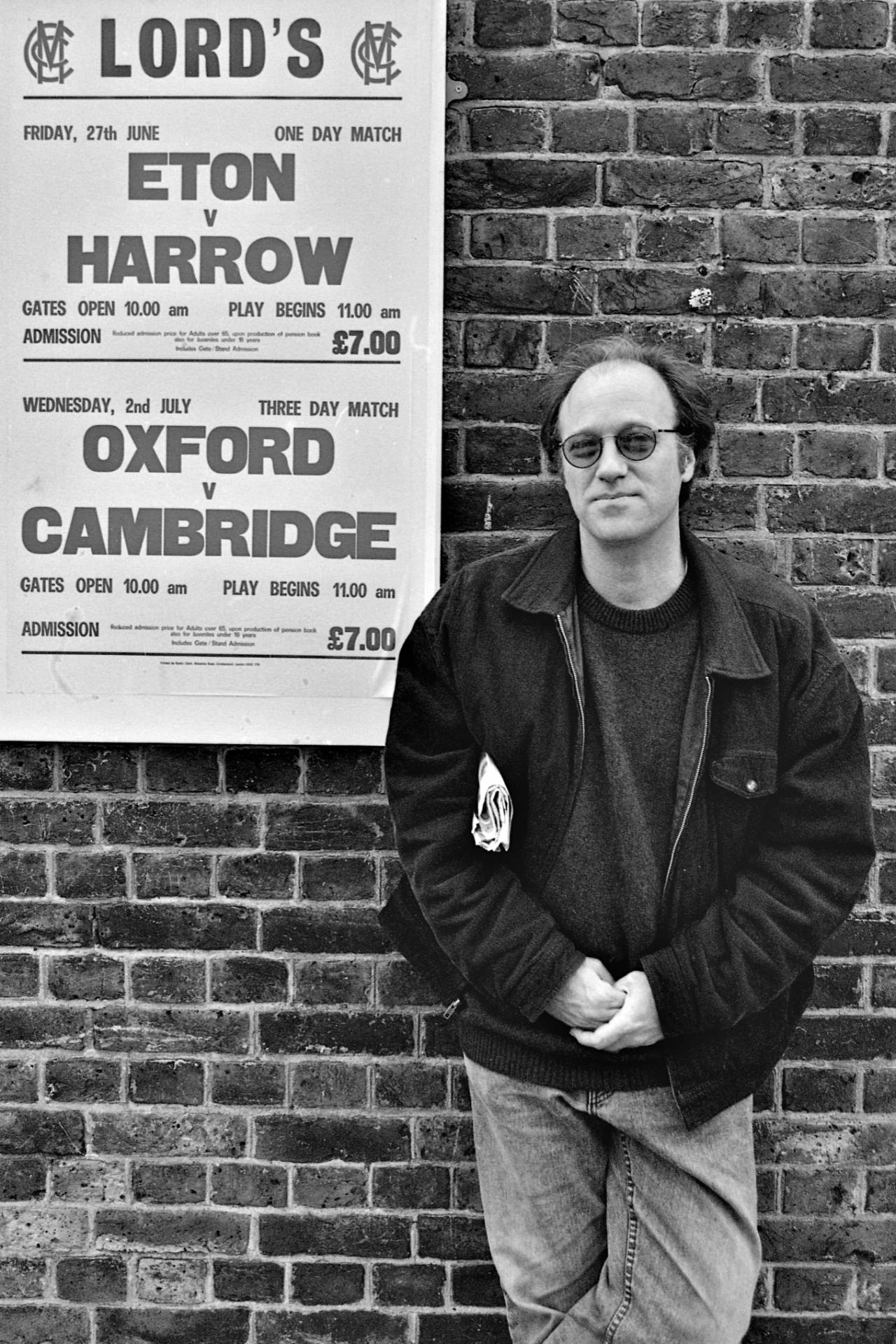

Marqusee: amiable, generous of spirit and blessed with a sense of humour that was often directed at himself • Mark Ray

"Losing Mike is like losing several pints of blood. I'm left dizzy by the prospect of his absence. I'm a sportswriter because Mike Marqusee made me one."

Almost everything you need to know about the significance of Mike Marqusee, who died on Tuesday at the depressingly premature age of 61, is that the author of that grateful personal requiem is Dave Zirin, sportswriting's reigning conscience-in-chief. Zirin is neither English nor Indian, nor even a cricket writer, but an American whose preferred trivial pursuits are baseball and basketball.

That two of the most searching and insightful books ever written about cricket, Anyone But England: Cricket and the National Malaise (1994), a fearless yet soulful dissection of the game in his adoptive home, and War Minus The Shooting, a visionary, unflinching diary of the 1996 World Cup, have been the work of another American remains a firm vote for the benefits of outsiderhood. In fact, in almost miraculously uncommon contrast to Zirin, a fellow New Yorker and one of many protégés, Mike was an American who not only followed but actually played cricket.

That love affair began when he was 10, at a summer camp in western Massachusetts; as fate would have it, one counsellor happened to be Australian, and passed on the "rudiments". Alien as it was to his beloved baseball, Mike was seduced by the "defensive aspect" of batting with a flat blade; it is not altogether fanciful to suggest that the key attributes, patience and perseverance, augmented by a compassion for the less blessed, aided his development as a political activist, author and journalist. I know several cricket aficionados who have been drawn to baseball, but only one who has travelled such a distance in the opposite direction.

Movies played their part too. When he moved to England he went to see Alfred Hitchcock's The Lady Vanishes for the umpteenth time; only then did he learn that "there was a lot more to the film than I suspected… Hitchcock satirised the infantile silliness of the cricket cult while using it as a metaphor for an England complacent under threat, but capable of being roused". Cricket, he discovered, was sport at its most metaphorical, a melting pot bubbling over with imperialism, nationalism, racism and class struggle.

Mike won a place at Yale but that love of Shakespeare prevailed: in 1971, he opted to study English literature at the University of Sussex and never went home. Having spent the previous four years protesting the Vietnam War and agitating for civil rights, this period brought a distancing from politics - somewhat surprising given the university's vibrant activism. Not until the end of the decade, by when Britain's dicey economy, racial fissures and polarised political parties had re-energised his interest, did he return to this arena, initially as a social worker. From then on, the quest for justice, equality, humanity and dignity underpinned everything he did.

Falling head over heels for India, it was there that he set his first book, Slow Turn, a warm, perceptive novel about nation and obsession. Anyone But England and War Minus The Shooting followed, the latter researched first-hand in the face of forbidding odds: "I assembled the most motley set of press credentials ever submitted to the Test and County Cricket Board. I don't know what they made at Lord's of the letters from the New Statesman (in its pre-Blairite days), The Caribbean Times, Race and Class, and the fanzine Johnny Miller 96*, but I was accredited for all the matches I wished to attend."

Equally searching and clear-eyed were landmark studies of Bob Dylan (Chimes of Freedom) and Muhammad Ali (Redemption Song); he even covered a world heavyweight title fight for the Financial Times in Las Vegas, an almost unthinkable merger of publication, sport, place and reporter. Yet while commanding respect on the subcontinent - where he was welcomed as a rare Caucasian cheerleader and graced the pages, among others, of the Hindustan Times and India Today - Mike was a prophet without honour in two lands: the US and Britain.

Cricket, Mike discovered, was sport at its most metaphorical, a melting pot bubbling over with imperialism, nationalism, racism and class struggle

A falling-out with the Socialist Workers Party - who gleefully accepted his donations then treated him like dirt - might have engendered cynicism in others, but Mike's heart was far too big for that. He should have covered cricket regularly for the Guardian, emulating his spiritual predecessor and inspiration, CLR James; that he seldom did said nothing complimentary whatsoever about the prejudices of those making such decisions.

All the same, it was testimony to his amiability and generosity of spirit that he was admired by many who saw both game and planet through less progressive eyes, such as Michael Henderson, Robin Marlar and Christopher Martin-Jenkins. Moreover, as his friend Huw Richards, the journalist and sportswriter, put it, his sense of humour, often self-directed, made him "the complete inverse of the stereotype of the humourless activist". EW Swanton's snottily disapproving review of Anyone But England tickled him enormously.

It says much for Mike's indefatigability that his final innings was his most rewarding. When bone marrow cancer was diagnosed, the most optimistic sentence was four years; he dug in for nearly twice as long. This was primarily attributable to the love and support of his partner, Liz Davies, a housing rights lawyer; it also testified to how much he still burned to say. To some, no doubt, he brought to mind Woody Allen's line in Annie Hall: "I'm a bigot, yes, but for the Left"; to those who knew and understood him, reason and moderation nearly always beat righteous indignation.

He continued to write about cricket but devoted more time to poetry (a collection, Street Music, was published in 2012) and an important brace of bracing books. First, in 2008, If I Am Not For Myself: Journey of an Anti-Zionist Jew, an acclaimed, moving, memoir-cum-manifesto; then came last year's The Price of Experience: Writings on Living With Cancer, described by one reviewer as "insightful, inspirational, and full of warmth towards the staff who cared for him… and righteous anger at the spivs and racketeers who are destroying the National Health Service".

Those who only cricket know cannot fully appreciate Mike's contribution to our enlightenment. The game's role in his life, nevertheless, should never be underestimated: here, despite everything, was joy. How apt, then, that the last of his never less than wise musings to pass these eyes was his essay in Wisden India 2014 - "Why Cricket?" What on earth, he wondered playfully, would aliens make of such a peculiar, even perverse activity? Even those who deplore his political convictions should remember him this way:

The Victorians developed their ethic of cricket (leadership, teamwork, character-building) because they were ashamed of their fondness for this silly game and sought a higher justification for playing it. In the 21st Century, in a world where economic "productivity" is the measure of the individual, where only what is "useful" is valued, cricket's justification is that it has no justification. It is a sublime exception, an oasis of the useless and the counter-productive.

So what exactly are the pleasures we seek in watching cricket? What desires does it satisfy? They belong to everything about us that is all-too human. Which is why they'd remain unintelligible to our extra-terrestrial visitors.

Mike was a good friend, a wholly admirable man and a peerless cricket writer. I already miss him badly. For those with the game's best interests at heart, the void will gape too.

Mike Marqusee's funeral will be held in London from 2.00-3.45pm on January 20. Further details from www.mikemarqusee.com

Rob Steen is a sportswriter and senior lecturer in sports journalism at the University of Brighton. His book Floodlights and Touchlines: A History of Spectator Sport is out now