'Our game is a mental game. Most of our work is between the ears'

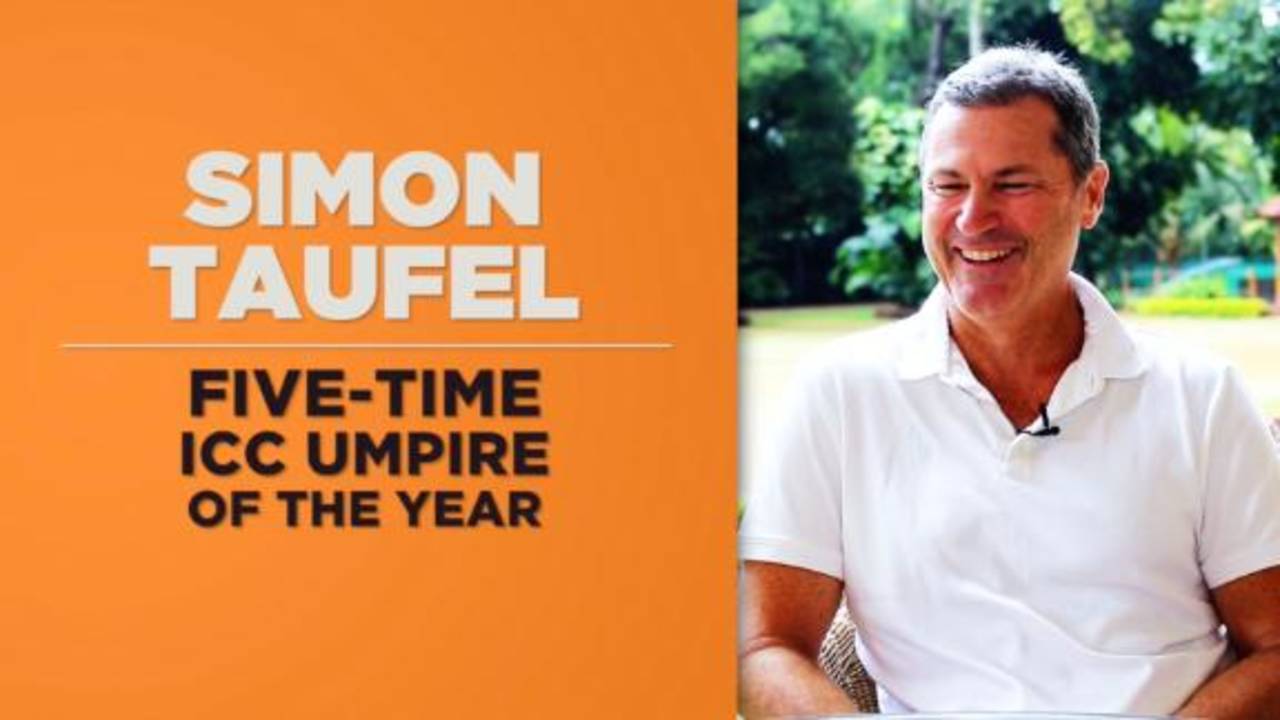

Former umpire Simon Taufel on the role of technology in umpiring, penalising player misbehaviour, and giving umpires access to support and resources the way players are

Interview by Shashank Kishore

26-Nov-2019

"Umpiring, like cricket, is a team game, so I feel embarrassed when people bring this up," Simon Taufel says when you ask him about being the ICC Umpire of the Year five years in a row from 2004 to 2008. After a stellar career at the top level, which he turned to after multiple back injuries put paid to his fast-bowling aspirations, Taufel branched out to being an umpiring performance consultant with the ICC and Cricket Australia.

While in India to launch his new book, Finding the Gaps, he spoke to ESPNcricinfo about modern-day umpiring, use of technology, player behaviour, and the need for support systems for umpires, among other things.

The ICC is trialling having a match official dedicated to detecting no-balls to remove the burden on the on-field umpires. Are you in favour of this?

We have been trialling this since the 2004 Champions Trophy. I have not seen the detail of what the current trial involves. In 2016 we carried out a trial when England hosted Pakistan in an ODI series, with the third umpire doing that [looking at no balls]. I would be interested to find out what makes this trial different to what we have already looked at.

We have been trialling this since the 2004 Champions Trophy. I have not seen the detail of what the current trial involves. In 2016 we carried out a trial when England hosted Pakistan in an ODI series, with the third umpire doing that [looking at no balls]. I would be interested to find out what makes this trial different to what we have already looked at.

What we do know is that it is very difficult for an umpire to stand where they do and get every one of those calls right. I think it is important to look at data on how many deliveries have been bowled over a certain period of time, and how many [no-ball calls] we're getting right and wrong, which umpires does that involve, are we able to help the umpires upskill initially before having to rely on technology? So there are a number of factors there to be reviewed.

As a young umpire, how did you juggle the challenge of watching for the front-foot no-ball and then immediately having to look up for the next part of your decision-making?

I still do (laughs). Umpires need to make decisions and we shouldn't be de-skilling where possible. But it's not just about the front-foot no-ball. There are other decisions where it's important to know where the ball is delivered from, such as an lbw, that are still part of that routine. I think it is narrow in the view that it's all about the no-ball. As an umpire, you need to know whether the ball is delivered close to the stumps or far away, and the only way you can do that is by knowing where the foot is landing.

I still do (laughs). Umpires need to make decisions and we shouldn't be de-skilling where possible. But it's not just about the front-foot no-ball. There are other decisions where it's important to know where the ball is delivered from, such as an lbw, that are still part of that routine. I think it is narrow in the view that it's all about the no-ball. As an umpire, you need to know whether the ball is delivered close to the stumps or far away, and the only way you can do that is by knowing where the foot is landing.

"It's easy to sit back in our lounge chairs and make objective judgements - if we get something wrong, there's no accountability for that"

Do you think players still don't completely understand the DRS, considering a healthy proportion of the reviews are usually unsuccessful?

I was reading Tim Paine's comments with interest after the last Ashes series. It was interesting to see him acknowledge that umpiring is difficult, and perhaps he now appreciates how tough umpiring is from a decision perspective. I think they [Australia] got six right out of 23, which is an accuracy of 26%.

I was reading Tim Paine's comments with interest after the last Ashes series. It was interesting to see him acknowledge that umpiring is difficult, and perhaps he now appreciates how tough umpiring is from a decision perspective. I think they [Australia] got six right out of 23, which is an accuracy of 26%.

It would be nice to see more captains and players do an umpire's course and stand and see what it is like to be an umpire, because we do think differently, and I respect the fact that players think differently as well. If you are going to step into the shoes of making decisions - decide whether it's right or wrong - it's important to start engaging with umpires and the officiating community about why we make decisions that we do, what goes into a decision, and how they can look at those rationally than emotionally.

What about the umpires' call - has it actually helped? Do you think it has been exploited in any way?

I think umpires' call is exactly the right thing to do, because umpires should be making decisions. So when they have a fair-catch scenario or obstructing the field, and the umpire makes a soft signal, that's a decision. The second thing is, they're then not sending the decision upstairs to give the benefit of the doubt to the batsman. They're actually saying, "The umpire has made a decision on the field. Can you conclusively prove and demonstrate that the on-field decision is not right?"

I think umpires' call is exactly the right thing to do, because umpires should be making decisions. So when they have a fair-catch scenario or obstructing the field, and the umpire makes a soft signal, that's a decision. The second thing is, they're then not sending the decision upstairs to give the benefit of the doubt to the batsman. They're actually saying, "The umpire has made a decision on the field. Can you conclusively prove and demonstrate that the on-field decision is not right?"

When there's no conclusive evidence to the contrary, the umpire's call stands. So that's a good thing for the game, because what happens if the cameraman doesn't get the shot, if the replay is inconclusive? We just automatically give the benefit of the doubt to the batsman, whereas the benefit of the doubt should go to the umpire's decision that they've made.

Are umpires trained to deal with the public scrutiny or backlash that comes with decision-making?

We are getting better in that space, but there's always room for improvement. Our game is a mental game; most of our work is between the ears. I think there's always an opportunity to build resilience and coping mechanisms. The game will continue to test you in those areas and you've got to work out strategies.

We are getting better in that space, but there's always room for improvement. Our game is a mental game; most of our work is between the ears. I think there's always an opportunity to build resilience and coping mechanisms. The game will continue to test you in those areas and you've got to work out strategies.

More resources need to be given to match officials in the same way they do with the players. We need support-mechanism programmes to be able to cope with the challenges of elite sport in very public environments.

"I started out as a third umpire with no training, no preparation. I was told, 'Here's the equipment, just do it.' We've come a long way 15 years later"•AFP

You're talking about mental health, an aspect that has gained as much importance in cricket as physical conditioning.

Yeah, absolutely. We've seen some of our colleagues in the past needing extra support. Guys like Mark Benson come to mind. It's really important that we have those programmes and resources in place to deal with that from a preventive point of view, but also a responding perspective that when they do happen, we're able to deal with them.

Yeah, absolutely. We've seen some of our colleagues in the past needing extra support. Guys like Mark Benson come to mind. It's really important that we have those programmes and resources in place to deal with that from a preventive point of view, but also a responding perspective that when they do happen, we're able to deal with them.

You must have evolved as an umpire under a system that didn't provide such access. How did you cope?

There were lots of things that needed to be improved by the time I hit international cricket. I started out as a third umpire with no training at all. No one knew if I was a good third umpire. I had no training, no preparation. I was told, "Here's the equipment, just do it." We've come a long way 15 years later, where we do simulated activities. Basically we do a third-umpire's net session before every game by going through videos, Skype sessions with coaches. That shows the evolution in training and development. But not every country has an umpire's coach, umpire's trainer or a development programme. Those are the things we try to continually advocate for to actually help match officials deliver the best, to make sure they're ready and to benchmark what they can do and make sure they deliver a minimum level of excellence to the game.

There were lots of things that needed to be improved by the time I hit international cricket. I started out as a third umpire with no training at all. No one knew if I was a good third umpire. I had no training, no preparation. I was told, "Here's the equipment, just do it." We've come a long way 15 years later, where we do simulated activities. Basically we do a third-umpire's net session before every game by going through videos, Skype sessions with coaches. That shows the evolution in training and development. But not every country has an umpire's coach, umpire's trainer or a development programme. Those are the things we try to continually advocate for to actually help match officials deliver the best, to make sure they're ready and to benchmark what they can do and make sure they deliver a minimum level of excellence to the game.

What do you look to get out of a net session as an umpire?

There are a number of things we encourage umpires to look at. Things like front-foot no-ball judgments and looking at the pace and bounce of the practice nets. In India, for example, a lot of practice nets are at the ground, so you get that simulated experience of what the pitch might play like. Also, you try and build relationships with the players, particularly the bowlers, or look at styles and strategies of batting with some new batsmen who might come into the team to get a feel for how they play. Or just meeting new players and building some familiarity. There's a wide range of things you can do at the nets from a preparation point of view that's important for that game.

There are a number of things we encourage umpires to look at. Things like front-foot no-ball judgments and looking at the pace and bounce of the practice nets. In India, for example, a lot of practice nets are at the ground, so you get that simulated experience of what the pitch might play like. Also, you try and build relationships with the players, particularly the bowlers, or look at styles and strategies of batting with some new batsmen who might come into the team to get a feel for how they play. Or just meeting new players and building some familiarity. There's a wide range of things you can do at the nets from a preparation point of view that's important for that game.

Can you recall a game where you needed the kind of support mechanism you've talked about?

In terms of preparation, resilience and coping with pressure, a couple of games stand out. The India-Pakistan 2011 World Cup semi-final in Mohali is one where I tried some strategies to block out external pressure and focus on team success with other umpires and referees, because team success is really important.

In terms of preparation, resilience and coping with pressure, a couple of games stand out. The India-Pakistan 2011 World Cup semi-final in Mohali is one where I tried some strategies to block out external pressure and focus on team success with other umpires and referees, because team success is really important.

At Headingley between England and New Zealand in 2004, I made a number of mistakes and got into a vicious circle of self-criticism and self-doubt. My coach put me onto a book called Winning Ugly by Brad Gilbert. I didn't read that on the plane across to England. But feeling in a very negative space on the flight home, I started reading it and the penny started to drop straightaway when Brad talked about beating yourself up, getting into a negative headspace and not talking to yourself in a very supportive way. I realised I was doing all those things I shouldn't be doing, and things I should've addressed at the time. I'd encourage people to read and get familiar with it.

"It would be nice to see more captains and players do an umpire's course and stand and see what it is like to be an umpire"

Player behaviour is something the ICC and even the member boards have agreed needs to be policed closely. Rohit Sharma escaped a fine and punishment for using profanity against a team-mate - albeit without intending any malice - last month. Is there a case to caution or penalise players in such cases, since it sets the wrong example for young fans?

There are rules, there's a policy, and it's pretty clear what the code talks about. It's up to the umpires to decide if someone has breached the code or not. A lot of it can be subjective, but I would encourage people to think about the questions we pose when we sit down to lay a charge as umpires. What does the game expect us to do? Do they expect us to lay a charge or not? And two, what happens if we don't do something here? Is that standard of behaviour acceptable? Would that be acceptable every game, every day?

There are rules, there's a policy, and it's pretty clear what the code talks about. It's up to the umpires to decide if someone has breached the code or not. A lot of it can be subjective, but I would encourage people to think about the questions we pose when we sit down to lay a charge as umpires. What does the game expect us to do? Do they expect us to lay a charge or not? And two, what happens if we don't do something here? Is that standard of behaviour acceptable? Would that be acceptable every game, every day?

When we answer that question, it leads us to what comes next, because in a team environment, we get caught up with who is right and who is wrong, what is chargeable and what isn't. You have to take the person out of the equation and look into the issue, which here is behaviour. Is it acceptable or not acceptable?

What we encouraged at the international level is to share information. There are some tools and resources the ICC has to share - video, charges and reports - among all umpires in international and first-class cricket to help deliver consistency. It's a wonderful thing, consistency. It's an ideal, but we also have context. Every example is slightly different and that's why the umpires are there to make a judgement call on laying a charge.

Where were you during the World Cup final, and what were your first thoughts when you saw Kumar Dharmasena adjudge the overthrows?

I was sitting at home and watching. It's easy to sit back in our lounge chairs and make judgements without other things going on around us. If we get something wrong, there's no accountability for that. We can say whatever we like. But when you're on the cricket field or in the third-umpire's box and have a pressure moment and you know you're accountable for whatever you do or don't do, that's the difference. Having been there and done that, I know what those guys [Kumar Dharmasena and Marais Erasmus] must have gone through.

I was sitting at home and watching. It's easy to sit back in our lounge chairs and make judgements without other things going on around us. If we get something wrong, there's no accountability for that. We can say whatever we like. But when you're on the cricket field or in the third-umpire's box and have a pressure moment and you know you're accountable for whatever you do or don't do, that's the difference. Having been there and done that, I know what those guys [Kumar Dharmasena and Marais Erasmus] must have gone through.

Overall, the standard of umpiring at the World Cup was very good. I don't think in a game of 600-plus balls to say one decision or one delivery was the deciding factor is fair. Two elements of the game were tied.

"Umpires need support-mechanism programmes to be able to cope with the challenges of elite sport in very public environments"•ICC/Getty

Have you had a chance to speak to Dharmasena after the incident?

Not Kumar specifically, but Marais has been in touch and we've had conversations about that. Kumar, from reading his comments about not regretting his decision to award overthrows to England, is owning his performance. That's a great quality. For him to acknowledge it takes courage. He's a very good umpire and will continue to be so because of his attributes of hard work and commitment. I expect nothing less from ICC Elite Panel umpires.

Not Kumar specifically, but Marais has been in touch and we've had conversations about that. Kumar, from reading his comments about not regretting his decision to award overthrows to England, is owning his performance. That's a great quality. For him to acknowledge it takes courage. He's a very good umpire and will continue to be so because of his attributes of hard work and commitment. I expect nothing less from ICC Elite Panel umpires.

Recently, there has been talk about helmets for umpires. Do you think they should be made mandatory?

I'm aware of John Ward's incident in India when he was on an exchange programme from Cricket Australia, and a few incidents in the IPL. Deflections off a bowler's hands or when they pull away from a catch - it can get hard.

I'm aware of John Ward's incident in India when he was on an exchange programme from Cricket Australia, and a few incidents in the IPL. Deflections off a bowler's hands or when they pull away from a catch - it can get hard.

Safety is a personal thing. I know as a batsman I couldn't get used to batting in a helmet, so I didn't. But these days it is mandatory to wear helmets. From an umpire's perspective, we need a lot of peripheral vision, and helmets do impact that, so I'm not sure helmets in their current form would be ideal. But it's certainly true that a lot of umpires are starting to think of chest guards, arm shields. That's a matter of personal choice. If you feel comfortable and safer, that's great, but for me it's more about having to look straight, down and sideways and not have any of the vision impacted. That will make me uncomfortable, so there's always a bit of a trade-off there.

When did you decide to write a book about your experiences as an umpire?

When I stopped working for Cricket Australia, about a year ago, I had a bit of time on my hands. I started up a company called Integrity Values Leadership with two partners, and a part of that process was to try and spread what I'd learnt from my experience in cricket umpiring and pass it on to corporates, young parents, boys and girls, other sports officials, and players.

When I stopped working for Cricket Australia, about a year ago, I had a bit of time on my hands. I started up a company called Integrity Values Leadership with two partners, and a part of that process was to try and spread what I'd learnt from my experience in cricket umpiring and pass it on to corporates, young parents, boys and girls, other sports officials, and players.

I sat down with a blank whiteboard, brainstormed on various different issues, incidents and experiences, and came up with 17 chapters around various personal experiences -such as the Lahore terrorist incident, what we learnt from that, what it was to go through. Then I looked at those transferrable skills that many people ask me about, like what it takes to get to the top of elite sport in your chosen field and how you stay there. What I have learnt, what worked for me and what did not. It took a couple of months to write. Took me longer to find a publisher! And here we are launching it across India. It has been fantastic.

Shashank Kishore is a senior sub-editor at ESPNcricinfo