The torture makes the genius?

For all the perspective he gained later in life, would Martin Crowe have been the batsman he was if not for the disharmony within him?

Ed Smith

Mar 7, 2016, 8:34 AM

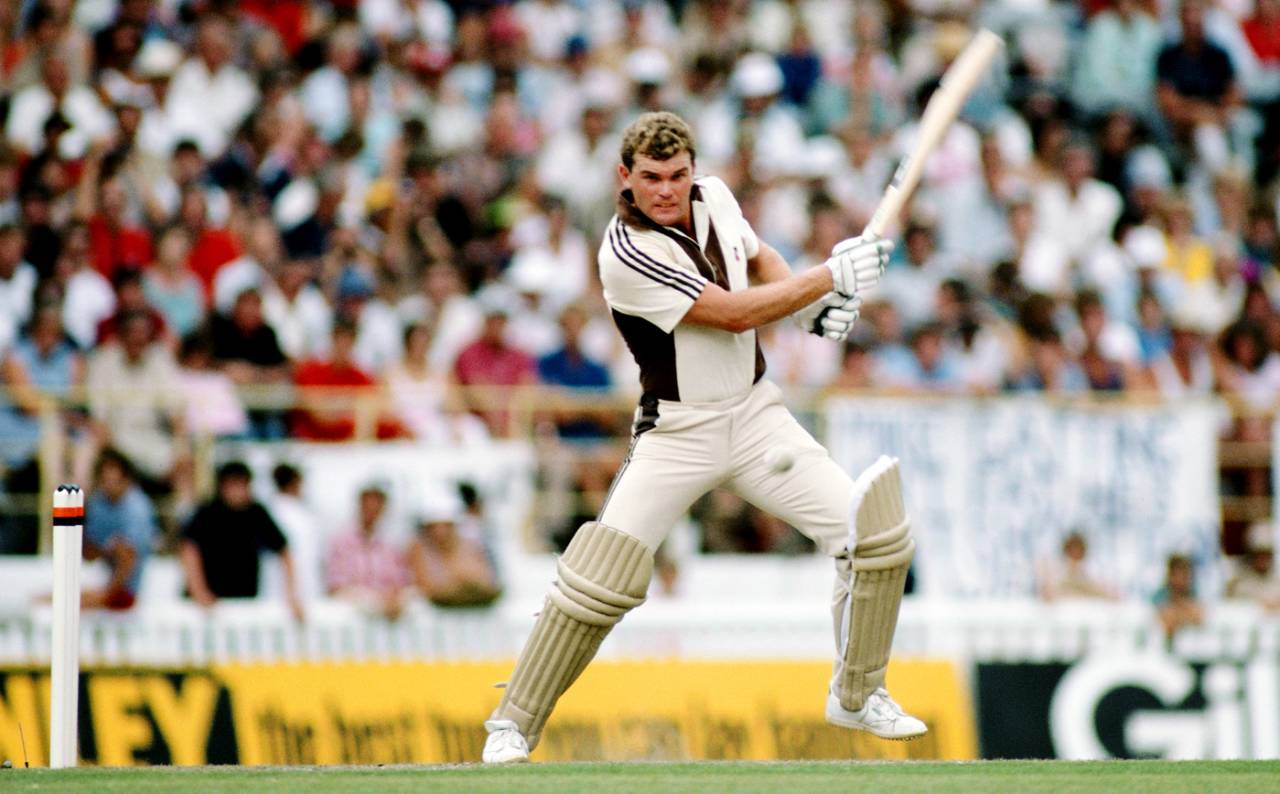

Martin Crowe said cricket destroyed his spirit, but what was it inside him that drove him to succeed? • Getty Images

Martin Crowe did not take the easy path, and I cannot evade his example as I try to find words for his life. He would not have wanted affection or admiration to varnish the writer's sense of the truth. So let me try.

I experienced only the best of Crowe. First, as a spectator, I thrilled to Crowe's classical elegance - his touch, balance and finesse. As with GS Chappell and ME Waugh, after watching only a few balls you knew that's how you wanted to play - if only you could. He stood tall but never static, his body sideways but the eyes level, his footwork decisive but unobtrusive, the bat swing fluid and natural - as though batting was his calling, the way he'd been made.

Then I was lucky enough to get to know him as a correspondent. Re-reading all his emails, I see that he picked out different things from most readers: he responded to what he called "authenticity", never to mere cleverness. He looked for the deep river, not the tributary. As Matthew Arnold put it:

Below the surface-stream, shallow and light,

Of what we say we feel - below the stream,

As light, of what we think we feel - there flows

With noiseless current strong, obscure and deep,

The central stream of what we feel indeed.

But a portrait that begins with the beautiful batsman, admired from the boundary edge, and ends with the generous correspondent leaves out the real story - and much of it, Crowe's life as it was lived, was troubled and problematic. We have Crowe's word for that.

In his autobiography Raw, Crowe described how "an innocent boy became a resentful man, a man who bore grudges… [who] became a world record-holder of grievances". He once told an interviewer, "No one seemed to like who I was and I don't blame them - I didn't like who I was either."

Crowe looked at cricket and counted the cost, how it "tortured me and destroyed my spirit". Like many before, he wondered what cricket had done to him.

There is a deeper question, I think, that gets to the core of Crowe's paradoxical suffering: what is it in us that makes us play cricket? Why do we - or at least, did we - seek fulfilment and happiness through sport, especially the winning? Is it childish and, if so, why has the child got such a tight grip on the man?

We often ask the question, does the player derive from the man, or does the man emerge from the player? The question is an oversimplification, of course, because the player and the man grow partly in tandem. But we tend to see things back to front. We reflect on a career and imagine cricket "did" things to us. In fact, surely there was a predisposition, present in childhood, to do things - to seek mastery, success, dominance and recognition - and those psychological needs were expressed through the vehicle of cricket. All of which comes at a high price, of course, often paid in the form of disappointment and the sense of falling short.

Very few athletes find sport to be "enough" to nourish a whole life. And yet the financial rewards that flow from professional sport make it ever harder for retired players to start over beyond the boundary

Blaming cricket is to give the scratch mark too much credit. What of the underlying itch? "Parents ambitious of turning a daughter into a future Jacqueline du Pre," reflected the novelist Zadie Smith, "might do well to smash up a cello in front of her."

All this casts Crowe's troubled streak in a different light. I suspect what Crowe sometimes disliked about himself - the slights harboured, the arrested development, the ambition unslaked, his unbalanced "ego" (his phrase) - at times partly drove him, sustained him and shaped him as a wonderful cricketer. The logic is uncomfortable, I know, but Crowe was surely right that we "cannot pick and choose which parts to keep or discard," as he wrote in an email to me. The torture was entangled with the talent.

I am an optimist about balance and perspective within great sporting lives. It is possible to live happily and also to play well. Possible but rare. For every Roger Federer, there are several John McEnroes. The moralist hopes that great sport and life can be balanced in harmony; the historian acknowledges it is not easily done.

That is why modern professional sport, all taken together, suffers from an unresolved tension, a fault line that has deepened since Crowe's retirement. Very few athletes find sport to be "enough" to nourish a whole life. And yet the financial rewards - and adjoining industries - that flow from professional sport make it ever harder for retired players to start over, beyond the boundary, outside the safety net. What we once looked for in sport - a way of winning the game of adult life - leads to its opposite, the avoidance of growing up. To adapt a famous dictum - "the practice of law sharpens the mind by narrowing it" - professional sport offers ever more grown-up rewards while perpetuating a state of infantilisation.

There is a second aspect to Crowe's life that might be slightly underestimated, despite all the excellent tributes. It has been widely agreed that he had a superb mind - unblinking, restless and innovative. But speak to people who worked with him - team-mates, editors, or players who were potential beneficiaries of his expertise - and the same word tends to crop up: "emotional".

At a dinner with several New Zealand players a few years back - they were playing then, after Crowe's era - I asked if they sought his insights on the game. Yes, came the reply. But he was emotional, always emotional. They meant, I think, that Crowe had a tendency to reach a conclusion with his emotions, and then his fine mind would flesh out the logical details. Van Morrison wondered what life would be like "if my heart could do the thinking". With Crowe, I sensed that's exactly how it was. His intelligence was emotional, even though he was not always emotionally intelligent (again, the testimony is his own).

A final irony is that Crowe was so prepared to lay bare his private ordeals. For otherwise, what would the public have seen? The first public figure was the apparently effortless technician, majestic and lordly, above the fray and beyond artisanal flaws. The second public life was the thinker on the game, equally deft and assured, his touch as a thinker no less certain than his own as a player.

And yet there was so much "below the surface-stream, shallow and light", which prompts a question we do not ask enough about our heroes: What do they go through in order to brighten the world that we experience, to lift it beyond the safety and ordinariness of compromise and perspective? Far from envy, a better framework is thanks.

Ed Smith's latest book is Luck - A Fresh Look at Fortune. @edsmithwriter