Robin Jackman

A man whose first ambition was to be an actor, pinnacle of Jackman's fame came in a non-speaking role

07-Oct-2021

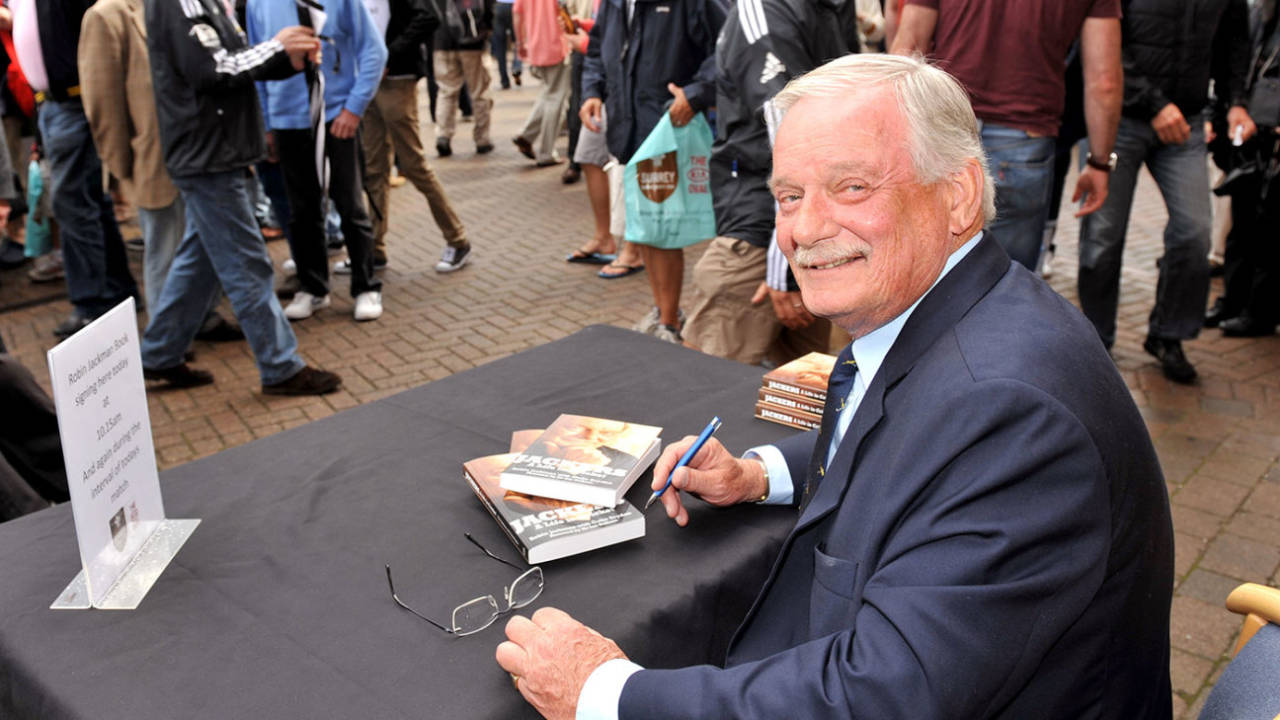

Robin Jackman died on Christmas Day, aged 75 • Getty Images

JACKMAN, ROBIN DAVID, died on December 25, aged 75.

For a man whose first ambition was to be an actor, it was a sad irony that the pinnacle of Robin Jackman's fame came in a non-speaking role. He was the centrepiece of a drama that convulsed world cricket and made ripples beyond: the Jackman affair.

In February 1981, Jackman was flown out to join England's tour of the West Indies to replace the injured Bob Willis. Unfortunately, the team were then in politically volatile Guyana. He was far from the only player in the party who had links with South Africa, still under white minority rule, and an international pariah. But the arrival of Jackman - who wintered there regularly - galvanised Guyanese militants. Three days after he arrived, the government ordered his deportation. The whole England party left with him, and it required frantic diplomacy to ensure the tour continued.

It worked out well enough for Jackman. He was already 35 and, after 15 years of outstanding bowling for Surrey, he finally made his Test debut a fortnight later in Barbados, played again in Jamaica, and twice more against Pakistan in 1982. He performed respectably, as he always did, without commanding the attention achieved on his brief visit to Guyana.

On the circuit, he was a personality. Alan Gibson, whose much-loved county reports in The Times mixed wisdom, whimsy and a little cricket, called him The Shoreditch Sparrow, placing him in the pantheon of The Oval's lively Londoners. In fact, Jackman was not a Londoner at all. He was born in India, where his father was an officer in the Gurkhas until he lost a leg in an accident. Invalided out, Colonel Jackman brought the family home to a 16-acre spread in Surrey, and bowled to his younger son tirelessly on his prosthetic limb in a net in the garden.

Aged 11, he was advised against the stage by his actor-uncle Patrick Cargill; he took the hint. At St Edmund's School, Canterbury, he topped the batting and bowling averages, but saw himself mainly as a batsman. He appeared for Surrey's Second XI aged 18, and the bowling started to take precedence. His first-team debut came in 1966, and he began to turn in some eye-catching performances, but with too many bad balls. Keen to improve, he arranged a close season in Cape Town where he fell in love for ever with the place, the life, and a trainee nurse, Yvonne, who became his wife. He also learned to bowl and bowl - in one club match he had a 57-over spell, interrupted only by lunch and tea.

In 1970s England he was among the leading wicket-takers year after year, an occasional pick for the small number of one-day internationals then played, and the regular subject of Test speculation. "He was unbelievably competitive," recalled Mike Selvey, the Middlesex seamer who became cricket correspondent of The Guardian. "In your face the whole time. He sledged mercilessly. And he was always at you with the ball. Very tight to the stumps, skiddy, moving it away. He was certainly quick enough, whatever anyone says about his pace." And he was still an actor-manque´. As Gibson put it: "He dashes about, waves his arms furiously, appeals loudly, scratches himself, and bends himself into knots to examine the soles of his boots."

In 1976, Jackman was convinced he was about to be called to Old Trafford as cover for John Snow, but was hurt in a car crash; Selvey got the call instead. In 1980, he had his year of years: 121 wickets at 15, including a county-best eight for 58 against Lancashire - helped, as he readily acknowledged, by the presence of the ferocious Sylvester Clarke at the other end - and a place in the England squad for the Centenary Test against Australia at Lord's. He got the bad news unofficially from the hotel receptionist when he checked in: "Ah, yes, sir. Just the three nights, I believe." Nothing else was said until next day, when the captain, Ian Botham, returned from the toss. "Oh, sorry, Jackers, I forgot to tell you. You're carrying the drinks I'm afraid, mate."

But his day did come - his first three Test wickets in Barbados were Gordon Greenidge, Desmond Haynes and Clive Lloyd - and in 1982 he bowled well in a tense win over Pakistan at Headingley, which ensured his place on the Ashes tour. This made him relieved about a snub several months earlier: even though he was already in South Africa, and the enterprise was run by a pal of his, he was ignored for the rebel tour led by Graham Gooch. But for that, he would have been ineligible for Australia. There was a lot of drinks-carrying there too, which was hard on a 37-year-old, and the prospect of a new job in the Cape led to a retirement announcement before the tour was over.

He finished with 1,402 first-class wickets, 1,206 of them for Surrey, putting him 11th on their all-time list. The job itself did not go to plan, but he had a successful stint coaching Western Province (he had played several seasons for Rhodesia), and later found a new niche. He had done a few BBC stints on radio and television, and eventually emerged as a star of TV commentary in South Africa. When he died, the Cape Times praised his out-of-fashion Benaudesque ability to let the pictures speak for themselves.

His playing contemporaries liked him a lot (except as an opponent), but never saw silence as his main attribute. A heavy smoker in his playing days, Jackman was diagnosed with throat cancer in 2012, and suffered further health problems before testing positive for Covid-19 as Christmas approached. He died two days after John Edrich, his long-time Surrey team-mate (and captain); they were both in the side that won the Championship in 1971, Surrey's first since the glory days of the 1950s. Jackman was a Wisden Cricketer of the Year in 1981.