Outsource the tampering

There has been enough talk about looking kindly on tampering, but what if it was done off the field?

Krishna Kumar

Nov 7, 2013, 2:56 PM

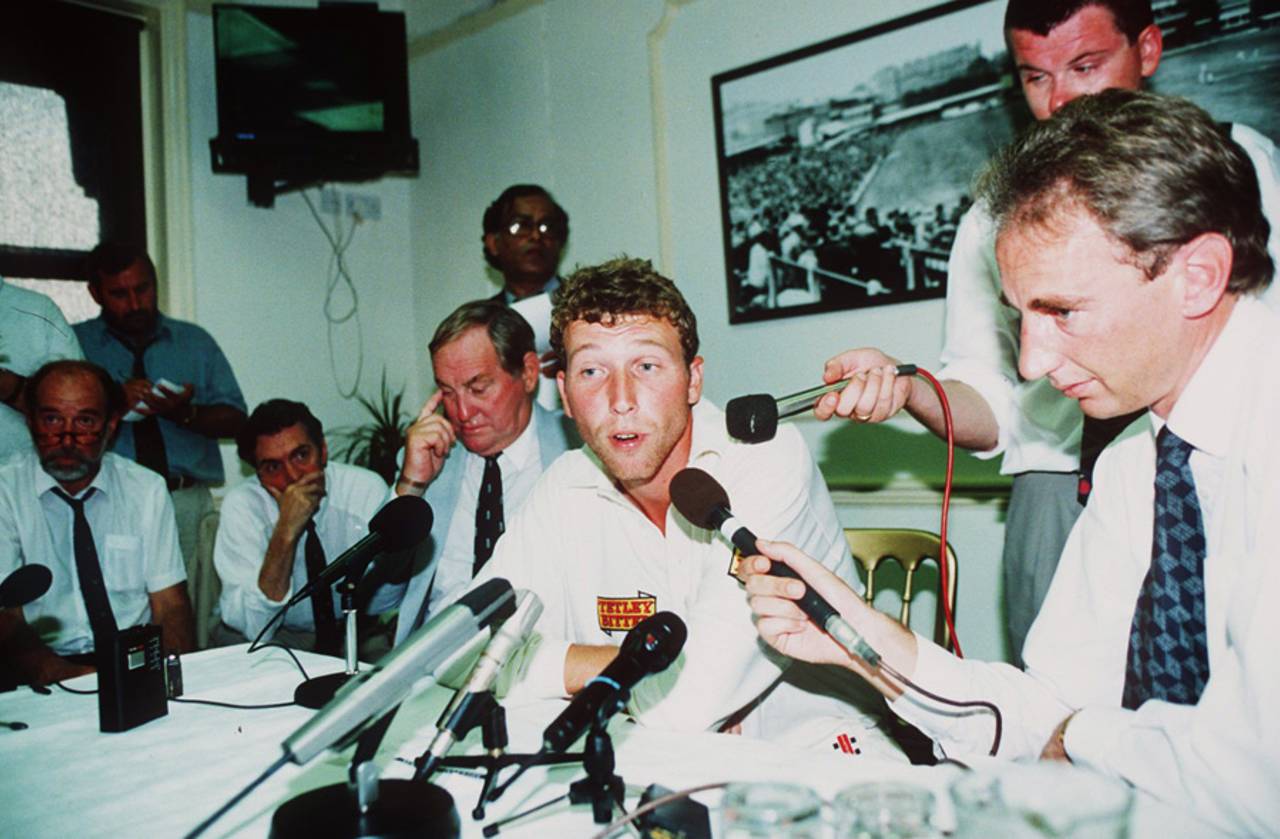

Ball-tampering is seen as a crime. Maybe it's time to legitimise it by giving it official sanction • Adrian Murrell/Getty Images

There's a fair amount of recent discussion that centres on encouraging ball-tampering so long as it doesn't involve external sources. The premise on which this argument rests states that this is finally something that levels the playing ground for bowlers. I'm not bothered by the difficulties of deciding what exactly constitutes an external source, although that is a long-winded matter in itself. What bothers me is: Did tampering start off solely as a reaction to the game being loaded in favour of batsmen? Or was it done with the specific, albeit unadvertised, intent to bend the rules? I'm fairly sure it wasn't the former. It's done in club games, for goodness' sake, and in conditions that are not biased in favour of batsmen by any stretch. The age-old vaseline shine is used quite a bit in club cricket. Ball-tampering has been happening for a long time, way before bats became sturdier and before pitches became more batsman-oriented. So perhaps we shouldn't get contexts mixed.

Apart from the original motivation, I've a basic question. If some teams are better at taking care of the ball, even using perfectly legitimate means, should this fetch them benefits in terms of performance? Need this knowledge of old ball maintenance be important for performance? There is innuendo after most series that one of the teams wasn't able to coax reverse swing out of the ball while the other was. The bowling of reverse swing is a skill that requires a natural full length, allied with genuine pace and loads of hard work to be effective, and hence deserves the recognition it has got. It could most certainly do without insinuations about the methods used to get the ball in suitable shape that cast aspersions on its practitioners.

So, what's the way out? A solution that suggests itself, if you go by this line of reasoning, is to get the tampering done off the field. If there is active discussion about taking the players out of the DRS process and giving it to the umpires, why can't a far more important aspect of the game be handed over to those off the field?

In Tests, it cannot be too difficult to get a bunch of suitably roughened balls and give the fielding team the option of using one of them, say, for starters, around the 50-over mark. Let the fielding team then maintain it till 80 overs, when the second new ball is due. Let them take care of the ball - in a positive manner. Leave the negative condition-altering, roughening part to a fairly standardised reverse swing-enabling, neutral external process.

While rightly celebrating reverse swing, let us also acknowledge there is a general greyness to the matter, and hence a lot of room for stretching the rules. Wouldn't it be better to just get rid of this perennially festering issue altogether? Once the roughening is off field, any on-field attempt at tampering can be more strictly dealt with.

With the greyness gone, I'd suggest increasing the penalty to, say, 30 runs, without punishing the individual player who is caught doing it, or the team in any other way. After all, it's the act that needs to be frowned upon and not the individual, and it's silly for an individual to cop the blame when it's done in the interests of the team. The five-run penalty doesn't make any sense whatsoever. It seems almost preposterous to suggest that ball-tampering has the same effect on a game as a ball that happened to hit a helmet placed behind the keeper.

So what would we have if a "new" old ball is made available around the 50-over mark? In conditions that hugely favour new-ball bowling, and where the shine doesn't wear off quickly, captains will have an interesting strategic call to make, and might delay taking the offered old ball. In subcontinental conditions, teams will surely opt for it.

With the threat of reverse swing definitely looming, batsmen might try taking a few more risks against spinners and do so earlier than is the norm today. Teams might be forced to select at least one fast bowler who can bowl reverse swing.

Once the 50-over "new" old ball practice is adopted in domestic cricket, more pace bowlers who can swing the ball will come through at an earlier age, and on a consistent basis, even in conditions that haven't traditionally favoured fast bowling. All this independent of whether teams at the domestic level are good at taking care of the ball appropriately - an ability that is rarer found at first-class level.

What can go wrong if this method comes into use? From a purely cricketing point of view, no serious drawback comes to mind immediately. Yes, the roughening process will go through a few teething problems in terms of implementation and standardisation. But certainly what is managed now on a cricket field can be replicated off it. After all, it is not a monumental leap from being able to have ready - as is current practice - a set of balls of varied wear and tear to replace in-use balls that have gone out of shape.

While this is generally the age of moving on, and legalisation, both of which doubtless have their benefits when set in contexts of empathy and transparency, I'd argue that the moving on in this case needs to be done in a more meaningful manner. Employing off-field means to achieve reverse swing and docking the team 30 runs, without punishing any one player, for on-field attempts at achieving similar results, would both fix the problem and punish the team in a cricketing way, rather than single out an individual.

Unfortunately this stands little chance of being implemented because it might sound too far-fetched at first glance. But surely it has the potential to set the game, and more importantly the players, free of a certain type of inhibition, and that can't be such a bad thing.

Krishna Kumar is an operating systems architect taking a teaching break in his hometown, Calicut in Kerala