Ranjitsinhji's many lives

The particular plight of the immigrant, his involuntary schizophrenia caused by his locational and cultural displacements, is a familiar trope today

Samir Chopra

Feb 25, 2013, 10:59 PM

|

|

|

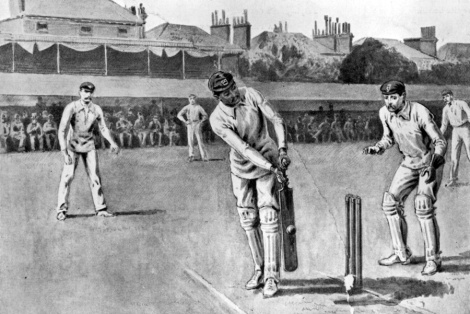

I've just finished reading Satadru Sen's remarkable book, Migrant Races: Empire, Identity and K.S. Ranjitsinhji. As might be evident from the title, the book is not primarily about cricket, and neither is it a straight-up biography of Ranji. But to read this academic, yet accessible, study is to understand a little better what a remarkable life Ranji lived, to add another piece to the jigsaw puzzle relationship of colonialism to cricket, and finally, to view today's world of cricket in just a slightly different light (compare the language used by colonial authorities to describe lazy natives in the 19th century with that used by cricket commentators to describe South Asian cricketers and you might just squirm a bit in your seat).

Sen's primary objective is to illustrate the multiple identities Ranji claimed and had foisted upon him: an exotic Indian in England, evidence of both the Empire's civilizing influence in making him an honorary Englishman, while simultaneously being a subject resistant to Englishness because of his inherent Otherness, and an England-returned Indian appearing both as a potential agent of modernizing change and a visible symbol of the decadence of Indian princely life. More than any other sportsman of the era, he was Englishman and Indian both.

Ranji's movement between these identities was fluid, and he was not always possessing of full agency when it came to transitions between them. In many ways, he was a tabula rasa for fertile imaginations: those that saw in him the magic and the darkness of the East and the power and brutality of the West.

Ranji was conscious of his multiple identities and he certainly aspired to occupy these roles when it suited him. Ranji moved physically, and he moved psychically: he lived in England, and then moved back to India. Among other things, he studied and played cricket in, and for, England, served in the Great War, returned to India to rule his princely state, became embroiled in disputes with colonial officers over the familiar issues of allowances, jurisdiction and federation, wrote books, cultivated long-lasting friendships with Englishmen (and women), and attended the League of Nations.

In doing all these, he managed to offend those that saw him as a symbol of Eastern decadence or indolence or insensitive princely power. He tried to please many, and didn't always succeed. When he did, it was often as a cricketer, sometimes as a friend, and only rarely as a ruler or Indian. The language used to describe Ranji, his cricket, and his character, is well worth calibrating against that used to describe subcontinental cricketers and cricket today.

The particular plight of the immigrant, his involuntary schizophrenia caused by his locational and cultural displacements, is a familiar trope today. The story of Ranji is a particular instance of this, except that Ranji was an exceptional immigrant in being possessed of a talent colonial masters of the time found useful to celebrate because it enhanced their standing.

In reading these transitions between identities, there is no point in asking, Who was the real Ranji? For the salutary effect of Sen's scholarship is to also illustrate just how much a function of our climes, our backgrounds, and our locations, our supposedly fixed and stable personalities are. Ranji just happens to have played a game which thrust him into the spotlight, and which made his struggles to stabilize his self an intensely public one.

Sen deserves the appreciation (and readership) of any cricket fan interested in understanding why cricketing politics and its attendant literature is such a rich, varied and complex business. This book is about a 19th century cricketer but it continues to illustrate the 21st century version of the game. Much has changed, but power and those who wield it, and resent its usurpation, are still players today.

Samir Chopra lives in Brooklyn and teaches Philosophy at the City University of New York. He tweets here