The Tendulkar-Brearley conundrum

The stereotype of the hero-worshipping Indian fan ignores evidence that seemingly skewed fandom is also present in supposedly more rational settings

Samir Chopra

Mar 21, 2014, 6:41 AM

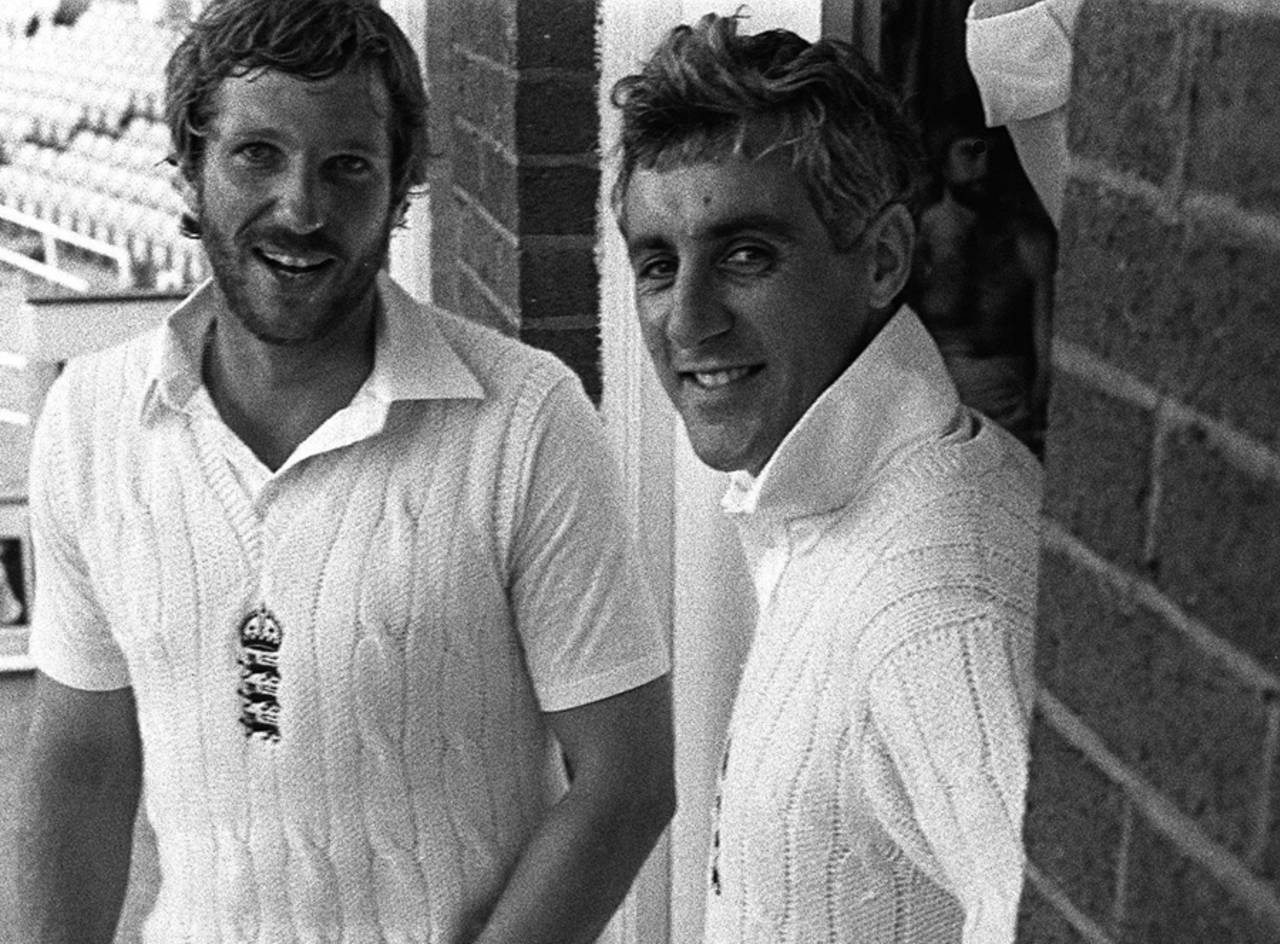

Mike Brearley's Ashes success in 1981 has formed the basis for uncritical appreciation and biography • PA Photos

A little while ago, in a tribute to Shahid Afridi, Osman Samiuddin wrote:

"… what struck me most about Tendulkar, much more than his batting, was his status as an unqualified hero. In Pakistan I always felt - and loved the fact - that we consider heroes to be a figment of the imagination, a whimsy of the privileged in a hard, mean world. Using Jinnah, the Bhuttos, and the Khans, Jahangir and Imran, to illustrate this tendency, I argued that Pakistan didn't, or couldn't, have the kind of hero Tendulkar was."

I think Osman falls prey here to a common affliction in Pakistani writing about India: the urge to distinguish Pakistani identity by distancing it from an Indian one - no matter how facile the distinction. Here it takes the form of suggesting Tendulkar enjoyed the status of an "unqualified hero" in the Indian imagination. (Osman does not explicitly name India or Indian fandom, but it is implicit in the claim above; certainly, much as Tendulkar might be admired elsewhere in the cricketing world, he isn't a hero anywhere but in India).

But Tendulkar never was an "unqualified hero" in India; if he ever had any such standing it was, all too often, in the eyes of those who wrote about him from afar, who saw in his following a convenient and glib representation of India's apparently unhinged devotion to cricket and cricketing heroes.

Tendulkar's status as a hero in India, to Indian cricket fans, was always qualified in some manner or the other. Many Indian fans were capable of mounting eloquent critiques of his batting in Tests, his captaincy, his often-rigid preference for batting positions in ODIs and Tests, his relationship with the BCCI, his delayed retirement, his caginess with the press, his acceptance of the Rajya Sabha nomination, and a host of other issues. Some of the most vigorously contested flame wars on the internet took place between those Indian fans who did regard him as God Incarnate, and those who didn't. It has become almost commonplace to suggest any criticism of Tendulkar would be met with a fierce avalanche of criticism from Indian fans. But much of this ire was directed at other Indian cricket fans who had dared to be critical of Tendulkar. And there were, I repeat, many.

The suggestion that Tendulkar's fan following in India was blind to all his faults always seemed a carefully constructed and unbalanced representation of the Indian fan, one that contributed to the Indian fan being viewed in the cricketing world as essentially irrational, devoid of sporting sense, sophistication, and subtlety and committed to the blindest forms of hero worship (or its flip side, irrational dislike of sporting figures). There were elements of all of this in Tendulkar-fanhood but they were not its only components. To describe it as such is to do injustice to a very varied group.

If Brearley had been a subcontinental captain, his record would have been dismissed out of hand, and indeed made the subject of much derisive commentary

Such a view of Indian fans and fandom ignores evidence that seemingly skewed hero worship is present elsewhere, in supposedly more rational and balanced settings. Consider, for instance, the admiration directed at Mike Brearley, whose legend - as captain and man-manager and psychologist rolled into one - only seems to grow by the year, carefully cultivated in a constant hagiography that often appears curiously blind to his actual playing record.

Brearley's central claim to fame is victory in a famous Ashes series, ranked as one of the greatest of all times, featuring incredible comebacks by the English team, one in which exceptional individual performances by Ian Botham and Bob Willis propelled an English side to a pair of improbable wins. These results were achieved at home, against an Australian side fatally racked by internal dissension and player cliques directed against the captain Kim Hughes. The Aussies were a house of cards already weakened from within, waiting for a puff to blow them down. Brearley's team supplied it.

For the rest of his captaincy career, Brearley led England to a pair of Ashes wins: the first, a 3-0* result at home in 1977, against another Australian side playing in the shadow of the Packer controversy (England 3-1), and the second, a 5-1 win in Australia in 1978-79, against an Australian side considerably weakened by the absence of their Packer players. Brearley also led England to wins against New Zealand (3-0 at home in 1978) and Pakistan (also Packer-depleted, two Tests away drawn in 1977-78, and 2-0 at home in a three Test series in 1978) and then later, in the 1979 summer, against India (1-0 in a four-Test series; at home again). Interestingly enough, when he led England against a full-strength Australia side in Australia in the 1979-80 Ashes That Weren't, England promptly lost 0-3 in a mini-whitewash.

If Brearley had been a subcontinental captain, this kind of record would have been dismissed out of hand, and indeed made the subject of much derisive commentary. One shudders to think of how an Indian or Pakistani captain might have been regarded had he possessed Brearley's batting and home-advantage-and-weak-opposition-biased record. But such is the image of the Ashes hero that all is forgiven, and instead it comes to form the basis for uncritical appreciation and biography.

In Brearley's time there was some notice paid to the fact that he was never a good enough batsman to hold his place in the English Test side (his average of 22 over 38 Tests without a Test century speaks for itself), and Phil Edmonds and Fred Titmus were skeptical about his reputed genius for man management (which was elevated to magical standards after his handling of the temperamental Botham and Willis in the 1981 Ashes).

But since his retirement these considerations seem to have vanished and his legend has shown a strictly monotonic increase. Journalistic assessments of Brearley often strike me as unqualified; but they are not generally regarded as such. His fandom appears literate, erudite, and possessed of the most rational of cricketing senses.

India has heroes just like Pakistan and England do, and their status is as contested as those of Pakistani and English ones. Tendulkar's status as an Indian icon is undoubted. But even in the Indian imagination, he occupies a complicated place. Acknowledging it would do more justice to the diversity of his following and the assessments directed at him. It would permit, too, a closer examination of forms of imbalanced hero worship that exist elsewhere in the cricketing world.

* An earlier version wrongly said the series result was 3-1

Samir Chopra lives in Brooklyn and teaches Philosophy at the City University of New York. He tweets here