The ball's swinging again

Seam bowlers have once again begun to pitch it up to the batsman and rely on swing. How will batsmen respond to the challenge?

Sanjay Manjrekar

22-Jul-2013

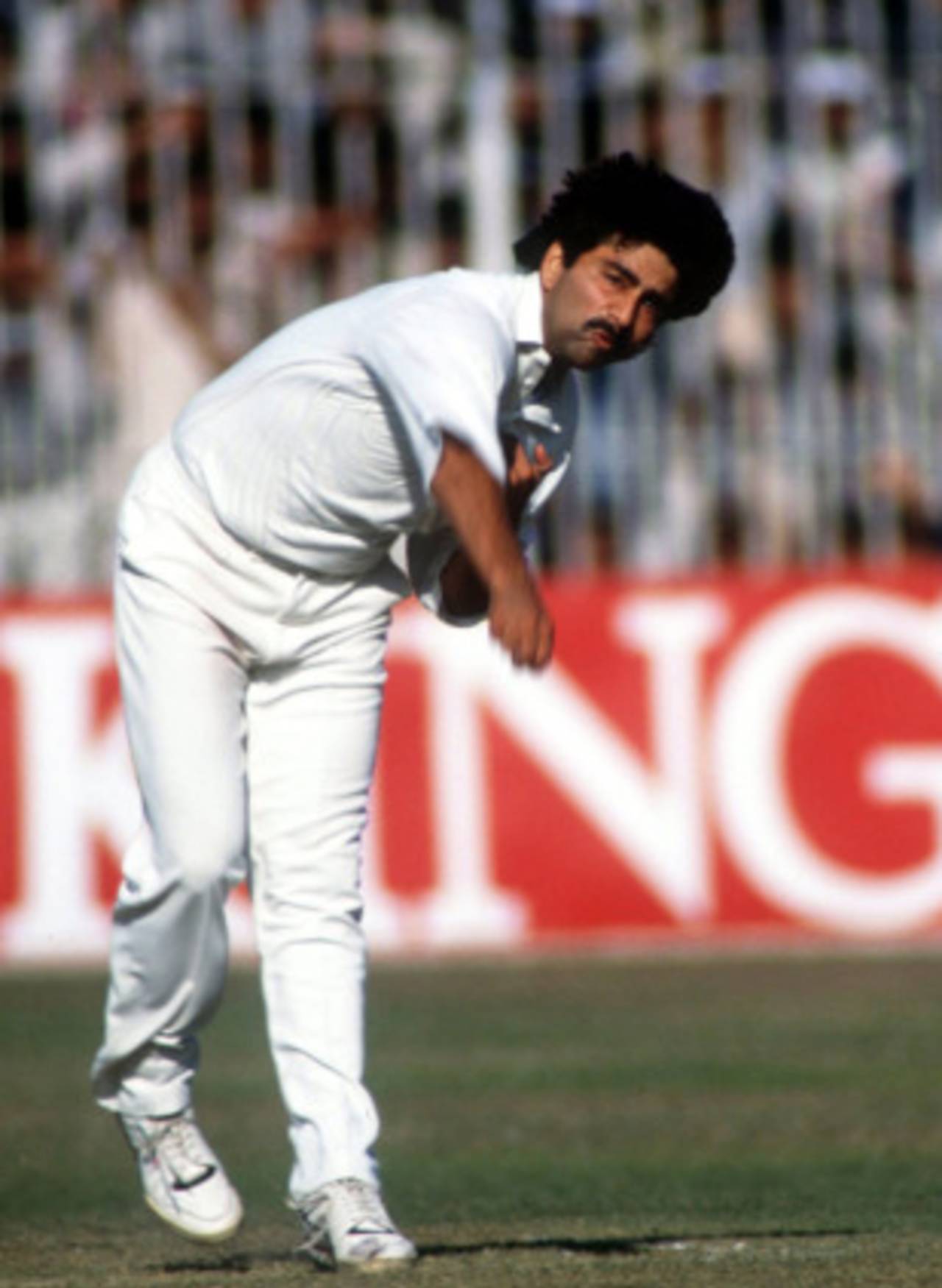

Prabhakar: sacrificed big early swing for late movement • Getty Images

Manoj Prabhakar may eventually be remembered in Indian cricket for the wrong reasons but there is no denying he was a very gifted swing bowler when he was first coming up the ranks in domestic cricket. At the time, by my estimation, he bowled at a maximum speed of 130kph, but he had the Bob Massie kind of big inswingers and outswingers, the kind we call "banana swing". Stories of how batsmen would leave balls from him wide outside off, only to find to them snaking back in to knock the stump out, did the rounds.

Prabhakar eventually got picked to play for India, and one of his early tournaments was the 1989-90 Champions Trophy, in that land of horrors for bowlers, Sharjah.

I wondered how the great Sir Viv Richards would play our new swing bowler. There was Prabhakar running in to bowl to Viv on a hot afternoon. The first ball was an outswinger; Viv hit it over covers for four. The next was a big inswinger; Viv hit it over midwicket for another four. Prabhakar's effect on the other West Indian batsmen was not too different. That day he experienced what a lot of other first-class cricketers do when they play at the highest level: a rude reality check about the big gap between domestic and international cricket.

But Prabhakar was not one to give up. He realised that to survive at this level it was not big swing that mattered but late swing. So he worked on cutting down on his prodigious early swing and focused instead on bowling it straighter and getting it to move late in the air and off the pitch, closer to the batsman. That is how he survived as an international bowler.

What Prabhakar did with minimal swing, Glenn McGrath mastered, albeit with more seam movement than swing. McGrath's stock wicket-taking ball was the one that deviated just a couple of inches off the pitch as it came close to the batsman. McGrath's ascendancy marked the decline of big swing.

This was an era of some wonderful bowlers who preferred hitting the deck, the likes of Craig McDermott, Curtly Ambrose, Courtney Walsh, Javagal Srinath, and later Andrew Flintoff, Steve Harmison and Makhaya Ntini. Success bore imitation, and with McGrath's success especially, a whole new generation of seam bowlers started bowling in the corridor, not looking for big swing in the air but for just a little movement off the pitch.

Pakistan remained, as always, a brilliant exception, sticking to their style of bowling it full and swinging it, as the world changed around them. For the rest, "hitting the right areas" became the mantra.

However, soon, much to the dismay of seam bowlers, pitches began to get flatter and bowling in these right areas slowly became less effective as a tactic. Most bowlers found that the ball did nothing much after it pitching.

Comfortable in the thought that the ball held no surprises, batsmen began to hit through the line. One-day and T20 cricket began to have their effect on batting as well. Think Sehwag and Gayle. The classical batsmen could be restrained by the shorter length in the corridor, but not these guys.

After the likes of Ambrose, Walsh, McGrath and Pollock followed Dale Steyn, James Anderson, Ben Hilfenhaus and Vernon Philander, who found that swing and seam bowled at full length brought benefits

In this time batsmen also realised that footwork as a part of technique was overrated, because they were able to plunder runs without moving their feet too much. In fact, by not moving their feet much they were able to gain room to get runs square of the wicket off balls that were close to off stump.

As a result bowlers became defensive, and "being patient and sticking to discipline" became their new cliché. Defensive fields began to be employed from the first ball of a Test match for such batsmen; bowlers chose to wait for them to make a mistake. But for how long could they just run in and get smacked around on those flat pitches?

They soon found a way of troubling these heavy-footed batsmen by bowling a lot fuller, trying to get that ball to swing so that batsmen who loved hitting through the line could be found out. The bowling style started to change once again. From the likes of Ambrose, Walsh, McGrath and Pollock followed Dale Steyn, James Anderson, Ben Hilfenhaus and Vernon Philander, who found that swing and seam bowled at full length brought benefits.

In England currently, we see bowlers like Peter Siddle, Stuart Broad and James Pattinson take the effort to bowl it full, looking to get the ball to swing rather than to "hit the deck" or bowl "in the channel".

And then there is Bhuvneshwar Kumar, who has rewound bowling to the early '90s. He is swinging it big, like Prabhakar did in his youth, to get some good top-order wickets.

Batsmen whose game was to stand and deliver have become easy prey for such bowlers.

Watching this Ashes, I have been amazed at how much fuller bowlers have been bowling, trying to get batsmen to drive off the front foot. This mode of dismissal was not so sought after a few years ago. About 30% of the balls bowled by the seamers from both sides in this series have been in the full, driving-length area. It was no different in the Test matches in India in 2012-13, or on India's recent tours to England and Australia.

Life is cyclical in nature and cricket is no exception. I think it is just a matter of time before batsmen make their own adjustments to this trend in bowling. It is impossible to survive a constant attack of full, swinging balls without proper foot movement. Footwork has to become relevant again. Time for the classical batsman to return to Test cricket.

Former India batsman Sanjay Manjrekar is a cricket commentator and presenter on TV. His Twitter feed is here