The good, the bad and the Greigy

Remembering English cricket's favourite punching bag, who didn't always do the right thing, but had unbridled passion for the game

Rob Steen

05-Feb-2014

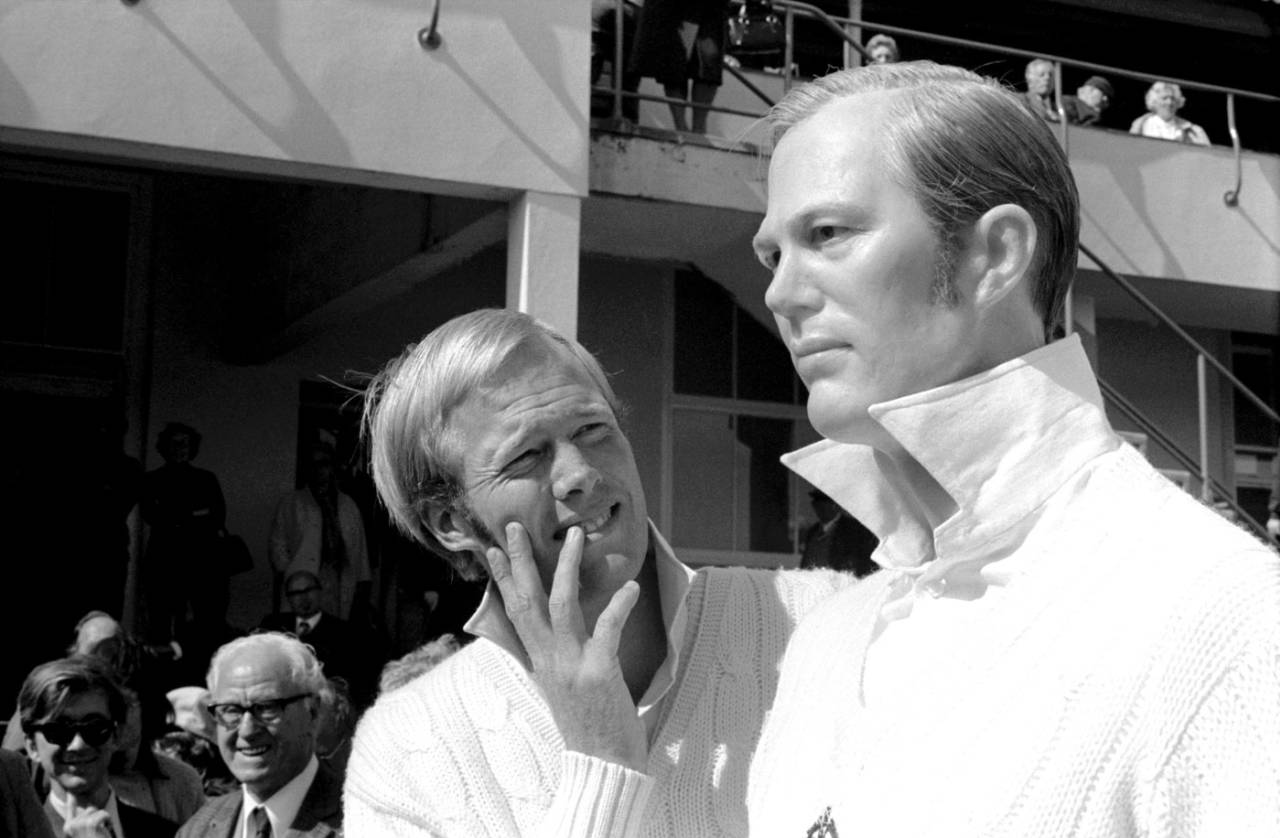

Tony Greig didn't care to mould his image to conform to English standards • PA Photos

Port-of-Spain, 40 years ago this week, and Tony Greig was, well, being Greigy. However inadvertently, he'd caused a row; a big, stinking cowpat of a row. To call it a force-ten gale of a storm in a teacup would be to misjudge the mood of the times. It should have been strenuously avoided by any England vice-captain, let alone a white, South African-born one in Trinidad while apartheid and racial unrest raged.

Despite the shaky evidence of a blink-and-miss-it TV bulletin, the cause appeared clear. Playing the last ball of the second day of the first Test to Greig at silly point, Bernard Julien heads off to the pavilion; partner Alvin Kallicharran, 142 not out, follows suit and Alan Knott pulls out the striker's stumps.

Greig's day, though, is not quite done: spotting Kallicharran "out of the corner of my eye", oblivious to the wicketkeeper's impromptu cessation, he throws instinctively at the non-striker's end, hits and appeals. Not having called time, umpire Douglas Sang Hue assents. Kallicharran stomps off, breaking his bat on the pavilion steps. The opportunist already knew he'd put his foot well and truly in the doo-doo. "As soon as I hit the wicket I thought, 'Oh dear, this could cause a problem or two.'"

Outraged spectators besieged the away dressing room; two tense, chilling hours inched by. Having correctly backed Sang Hue (he'd been right, technically if not spiritually), the West Indies board announced that the appeal had been withdrawn "in the interests of cricket generally and this tour in particular". The statement also asserted that Greig had "in no way intended his instinctive action to be contrary to the spirit of the game and he is truly sorry". Geoff Arnold was one of the nervier tourists: "They'd have killed us if we hadn't let [Kallicharran] bat the next day."

It was a sign of less fractious times when, in Georgetown 17 years later, Australia's Dean Jones fell foul of a similar miscarriage of justice. Bowled by a Courtney Walsh no-ball, he failed to hear the call, set off for the pavilion and was run out; and remained out, even though he had not attempted a run. Both captains, Allan Border and Viv Richards, admitted ignorance of the law.

Pietersen may be convinced he's been picked on, but has any sporting émigré endured the wrath - or, worse, snobbery - of his adopted home quite like Greig?

Opinions were anything but uniform in 1974: Derek Underwood blamed Kallicharran for not waiting until Sang Hue had lifted the bails; Keith Fletcher blamed skipper Mike Denness for not realising the Guyanan had been "cheated out" and refusing to reinstate him there and then. Denness' own memories wavered: interviewed shortly before his death last year by Dave Tossell, Greig's most recent and assiduous biographer, Denness recalled Knott uprooting the stumps; talking to Greig's first biographer, David Lemmon, three decades earlier, he made no mention of this. Whoever the watching Mick Jagger held culpable, it wasn't Greig. At lunch the next day, Mr Rolling Stone met Mr Equally Provocative on the pavilion steps: "Good work," enthused Jagger. "I don't blame you."

"We were going on to Jamaica after that, and we do know the locals can become quite volatile," reasoned Denness, explaining the climb down. "Also, I am looking at Tony's background and the way apartheid was then." Knott was similarly mindful.

As Denness walked towards the ground on the third morning, he was assailed by questions about "Kalli". Queuing spectators were carrying "little bags… full of empty bottles"; if Kalli didn't resume batting, he claimed he was advised, "they are for you". Before play, villain and reprieved shook hands in the middle, defusing the tension, but Kallicharran recently insisted on this site that he was "forced to do it".

Happily, for team, player and game, suggestions that Greig be sent home were repulsed: centuries in Bridgetown and Georgetown helped salvage draws before, back in Trinidad, 13 wickets for those lesser-spotted offbreaks earned a shared series. When Denness lasted one Test the following summer, Greig succeeded him as tosser-in-chief.

Further opprobrium would descend after that needling and entirely daft "We intend to make them grovel" overture to the sides' next encounter in 1976. Daft not just because it aroused the indignation of Andy Roberts and Mikey Holding, or because it was utterly insensitive to the social climate at the time - especially, again, coming from a white South African - but because not even his enemies could fairly characterise Greig as racist. Engaging brain before tongue never became a habit. Still, he had sharpened his diplomatic act come winter, bonding with crowds in India, where he is still fondly recalled as perhaps the most popular of visiting captains.

"I can't say I can think of anyone else who would have tried to do [what Greig did in Trinidad]," concluded Denness "He wanted to be in everyone's face the whole time." In defending Greig, Bob Willis went directly for the jugular, blaming his "uncompromising" South African background: "It would have been almost unthinkable for an English-born cricketer."

****

When Greig told us he was stricken with lung cancer, it was almost impossible to process. Greigy, vulnerable? The stand-up tough guy who took on Lillee and Thommo as resolutely as he faced down those mighty buffers at Lord's and the High Court, not to say epilepsy? The always-on performer who found a new lease of life as the game's loudest, proudest and most amorous cheerleader? At length, disbelief gave way to more dispassionate reflections. There was always a hint of fragility, something bravado could never fully conceal. Being an outsider is never easy. Ask our Kev.

Greig blazed a trail followed by many - too many, some have argued. Not until Kevin Pietersen did any match him for brass balls. English cricket, uncoincidentally, has enlisted no better South Africans. The difference between them, of course, is a matter of skin. Not pigmentation but thickness.

Pietersen may be convinced he has been picked on (and not without good reason), but has any sporting émigré endured the wrath - or, worse, snobbery - of his adopted home quite like Greig? Tough being KP? Compassionate as I am, he should have tried spending his career occupying the shoes of his predecessor as English cricket's favourite punching bag.

As Bruce Springsteen warranted, it's bloody hard to be a saint in the city, particularly when it's not your own. Greig was always too innate a competitor to compromise without a damn good fight. But for all his faux pas and foot-in-mouthings, there's one asset he possessed that helped him cope, one that Pietersen so palpably lacks: a reluctance to allow the brickbats to deflect him - though, to be fair, they do fly that much thicker, faster and further in this Twitter era. Had his skin been thinner, Greig would have been half the cricketer and a far lesser leader. Maybe that's why he was a far superior captain.

A salesman with cricket's best interests at heart•PA Photos

Only once did that skin prove too thin. In that cricketing-life-will-never-be-the-same Ashes summer of 1977, after Greig had announced his reviled decision to join Kerry Packer's magical mystery tour, the habitually kindly and fair-minded John Woodcock let anger get the better of him in the Times and vented his prejudices: the outgoing England captain was a traitor, he charged, because he was not "an Englishman through and through". Shades of Willis?

Being Englishmen through and through hadn't dissuaded four of Packer's other five Pommy signings, Knott, Underwood, Dennis Amiss and John Snow. Nobody cared that Bob Woolmer had been born in India. Despite that resilient hide and a Scottish father who had been one of the RAF's most daring and heroic fighter pilots during the Second World War, Greig bridled for decades over Woodcock's slight.

Beyond the cringe factor, one could only relish the unabashed enthusiasm and inclusiveness when Greig reinvented himself as a commentator able to dart between different audiences with ease, to soar over the thorny hurdles of language and culture. Chortle all you like at that early catchphrase "Goodnight Charlie" (no offence to the Vietcong intended, of course), but it is hard to recall a comment that did quite so much to lighten the mood as the game dragged itself, kicking and screaming about the good old days, into what may one day be hailed as its Accessible Age. Nobody sold the game quite like him.

That said, judging by the 2012 MCC Spirit of Cricket Lecture, which Greig gave at Lord's six months before his death, it is unlikely even he would have supported the latest sales pitch from Dubai. He really did save his best, and wisest, for last.

"Cricket as we know and love it has plenty of problems. Most of those problems can best be solved if the ICC members put the game's interests before their own interests; if India accepts the survival of Test cricket is non-negotiable; if India accepts its responsibility as leader of the cricket world; if it embraces Nelson Mandela's philosophy of not seeking retribution; and if it embraces the spirit of cricket and governs in the best interests of world cricket, not just for India and its business partners."

"You won't have Nixon to kick around anymore," said the self-pitying US president upon leaving office in disgrace. Greig might have had similar thoughts when he traded in the England captaincy for a lifestyle more befitting his talents, and wound up doing much to give the game a future. If only he was still around. The game needs lovers not businessmen right now, and few have been so ardent. For all those tactless moments, we could also sorely do with his transparency.

Rob Steen is a sportswriter and senior lecturer in sports journalism at the University of Brighton