When politics killed a tour

The planned 1970 South Africa tour of England divided the cricketing world, and left many grounds vandalised or surrounded with barbed wire

Martin Williamson

Jul 14, 2012, 3:05 AM

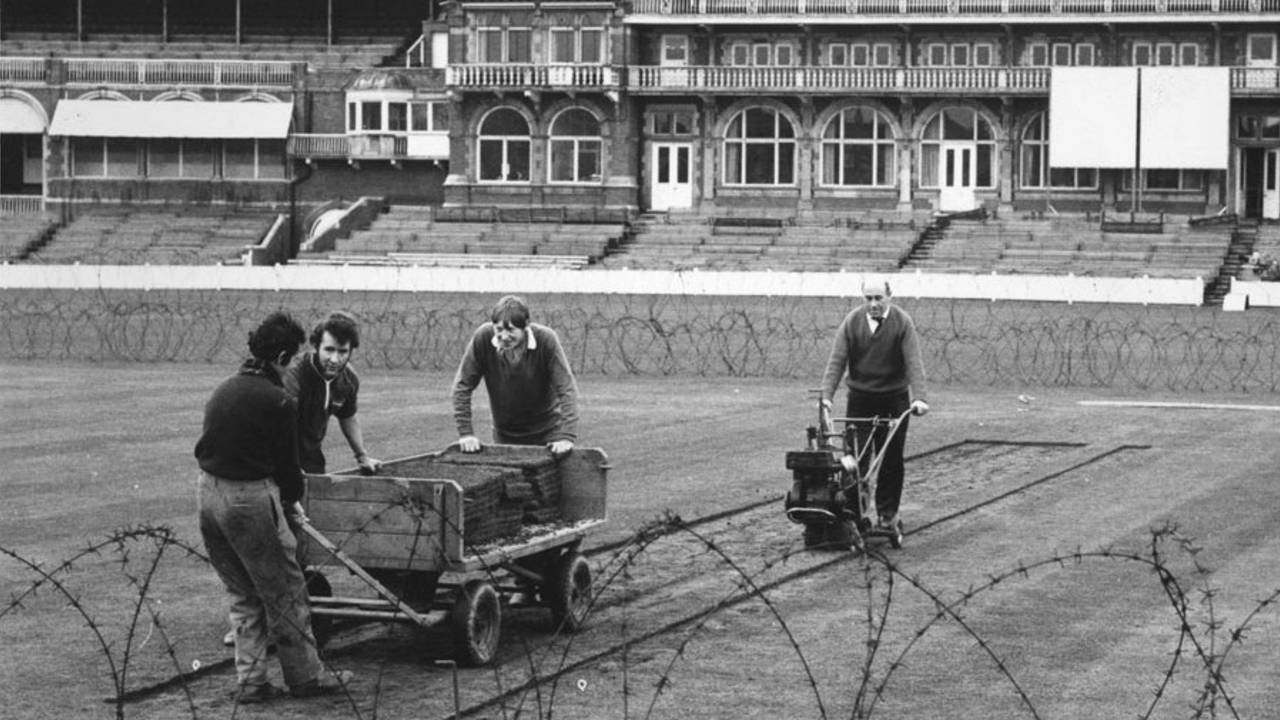

Security at The Oval ahead of the planned South Africa tour. Several other grounds started the season looking more like detention centres than sporting venues • The Cricketer International

The forthcoming Test series between England and South Africa has been keenly anticipated for some time, even if it has been unforgivably shortened to accommodate the home board's lust for cash. But 42 years ago the visit of the South Africans was a far from appealing proposition to many and the tour was eventually cancelled after a preceding winter of civil unrest and political squabbling. It was to be another 21 years before a South African team took the field again for an official match.

World opinion had been polarising against South Africa's apartheid regime through the 1960s, and while some sporting contacts with white countries remained, by the end of the decade it had become almost impossible for any South African team to tour overseas in an air of anything other than hostility.

In the autumn of 1968 a planned tour by the England side to South Africa had been cancelled because of the D'Oliveira affair. Despite that, the Australians had visited the Cape in 1969-70 and been thrashed 4-0 by a hugely impressive South Africa side that included Mike Procter, Barry Richards, Graeme Pollock and Eddie Barlow.

But ever since the 1968 cancellation there had been increasing disquiet at the prospect of the South Africans touring England in 1970, and it became a major concern after a tour by the Springboks rugby side in 1969-70 took place against a backdrop of violent demonstrations and civil disobedience. Games had been played in an often ugly atmosphere and security issues were highlighted when the team bus was hijacked en route to the England international at Twickenham.

Against this backdrop, the cricket establishment remained steadfast in its determination the tour should go ahead. The minutes of several meetings of the MCC and ICC show they were far more concerned with the impending metrication in the UK and how to cope with the change of pitch length from 22 yards to 20.12 metres and the weight of the ball weight from five and a half ounces to 155.8 grammes.

On December 12 the Test and County Cricket Board, the forerunner of the ECB, confirmed the tour would proceed, adding it was "averse to racial discrimination of any kind… and respected the right of those who wish to demonstrate peacefully". That was all well and good but protests had long since ceased to be peaceful.

The first indication of repercussions came a month later, when Kenya cancelled a visit by the MCC, stating it could not host a side when the club welcomed sides from South Africa. On the same day it was revealed weedkiller had been poured over the outfield at Worcester, the venue for the South Africans' first match. Soon after, sporting links with South Africa again hit the headlines when Arthur Ashe, the previous year's US Open tennis champion, was refused entry into the country on account of his colour.

The MCC and TCCB's carry-on-as-normal approach started to change, and meetings were held with the government over security surrounding the tour. It had become clear that the usual arrangements would be completely inadequate, and the cricket establishment was concerned the profit from the summer would be wiped out if it had to foot the bill. The fears were real. By the end of January, 12 county grounds had been vandalised.

Crisis, what crisis? The MCC committee meets in January to discuss the 1970 South Africa tour. Right up until the moment the UK government intervened, the MCC maintained that the tour would proceed•Getty Images

The killer blow came on January 30, when news broke that the International Cavaliers, a touring charity-based multi-racial side consisting of leading players, had been refused entry to South Africa. A letter from the South African Cricket Association concluded that "you must be aware any tour… including non-white personnel would not be allowed". The MCC tried to distance itself from the row, claiming the Cavaliers was a private enterprise and so nothing to do with it, but all that did was to make it look woefully out of touch with the world.

By mid-February the MCC had cut the itinerary from 28 to 11 matches, removing grounds deemed impractical to protect, and going so far as to approve the laying of artificial pitches on those grounds hosting games, to allow play to continue in the event of pitches being vandalised mid-match. If anyone on the MCC committee was still ignorant as to the scale of the situation, it was brought home to them: the meeting where this decision was made took place against a backdrop of the Lord's square surrounded by a protective barbed-wire fence.

As the tour grew closer, the press covered developments almost daily. Numerous letters to newspapers, both pro and anti-tour, reports of attacks against cricket grounds, and players and officials coming out one way or the other.

John Arlott announced he would refuse to commentate on any matches; other journalists subsequently joined him. While he said he was not sure protests at games were the answer, he felt that by allowing the tour to go ahead the Cricket Council had put cricket in a place where it would be "the ultimate and inevitable sufferer", adding the Tests "would offer comfort and confirmation to a completely evil regime".

In April, Harold Wilson, the prime minister, told the BBC that the MCC had made "a big mistake" in allowing the tour to take place. "Everyone should be free to demonstrate against apartheid," he said. "I hope people will feel free to do so."

The wider implications became more apparent when later that month eight African countries said they would refuse to participate in that summer's Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh if the tour went ahead. Within days they were joined by India, Guyana and Jamaica.

The AGM of the MCC in early May backed the tour without even needing a vote. On the same day, sodium chlorate was sprinkled on the wicket at Gloucestershire's county ground. There was no South Africa match scheduled there but the county team included Procter, one of their overseas players.

Peter Hain, who orchestrated the campaign to stop both the rugby and cricket tours, talks to a demonstrator outside The Oval at the start of the 1970 season. Hain went on to become a Labour cabinet minister•Getty Images

To general surprise the Oxford Union voted narrowly in favour of not disrupting the tour. Soon after, two students admitted "fiddling the vote". A second debate overwhelmingly supported active opposition.

Warwickshire said they would not pick any of their three coloured players for the match against the South Africans. The next day the gates at Edgbaston were vandalised.

As the cricket establishment steadfastly refused to budge, it found itself surrounded on all sides, under attack from politicians, the public and much of the media. More importantly, hotels refused to take bookings for the tourists (mostly on safety rather than moral grounds) and hundreds of policemen said they would refuse if told to protect venues from protestors.

On May 20, 12 days before the first match, the Cricket Council, the forerunner of the ICC, voted almost unanimously for the tour to go ahead. "It was agreed in the long term this policy was in the best interests of cricket, and of cricketers of all races in South Africa," explained the secretary, Billy Griffiths.

Bizarrely, the council stated there would be no further series involving South Africa "until SA cricket is played and teams selected on a multi-racial basis". If it was a sop to try to appease opponents, it failed. "The rulers of cricket stonewall on," said an editorial in the Daily Mirror. "If this is their last word, they are assuming a terrible responsibility."

But events were moving quicker than anyone realised. Three days later the Cricket Council called the tour off "with deep regret", following an official and strongly worded request to do so from James Callaghan, the British home secretary. Griffiths said he "regretted the discourtesy" to the South African board and went on to say he "deplored the activities of those who intimidate".

Wilson's government had decided that with a general election less than a month away the massive disruption and negative publicity that would result from allowing the tour to carry on could only harm Labour's chances of re-election. There were also fears it would trigger racial unrest within the country. The Commonwealth Games also risked being reduced to involving a few white countries, such was the level of threats to withdraw. Despite the endless mantra from those running cricket that sport and politics should not mix, it was politicians who took the final call.

John Vorster, South Africa's prime minister, was predictably angry. "For a government to submit so easily and so willingly to open blackmail is to me unbelievable." Ali Bacher, South Africa's captain, was more resigned: "I regret the manner in which politics have become involved in cricket… [but] unless we broaden our outlook we will remain forever in isolation."

As it turned out, that isolation, like the apartheid regime that caused it, was to last much longer than anyone feared.

What happened next?

- A hastily arranged five-Test series between England and Rest of the World was held in 1970. Ironically, several of those who would have toured with the South Africans played for the world side.

- South Africa's proposed tour of Australia in 1971-72 was cancelled in advance after widespread protests

- In September 1973 the planned tour of England by South Africa was cancelled (although it was still intended for England to tour there in 1976-77) and in its place it was decided to host the inaugural World Cup.

- Harold Wilson's Labour party lost the election in June 1970

- Vorster remained prime minister of South Africa until 1978, when he became president, but was forced to resign a year later, after a political scandal

Is there an incident from the past you would like to know more about? Email us with your comments and suggestions.

Martin Williamson is executive editor of ESPNcricinfo and managing editor of ESPN Digital Media in Europe, the Middle East and Africa