Step forth, über-quicks

Pat Cummins' arrival has caused excitement among fans of the game. Cricket must do everything it can to preserve and nurture fast-bowling talent such as his

Ian Chappell

23-Oct-2011

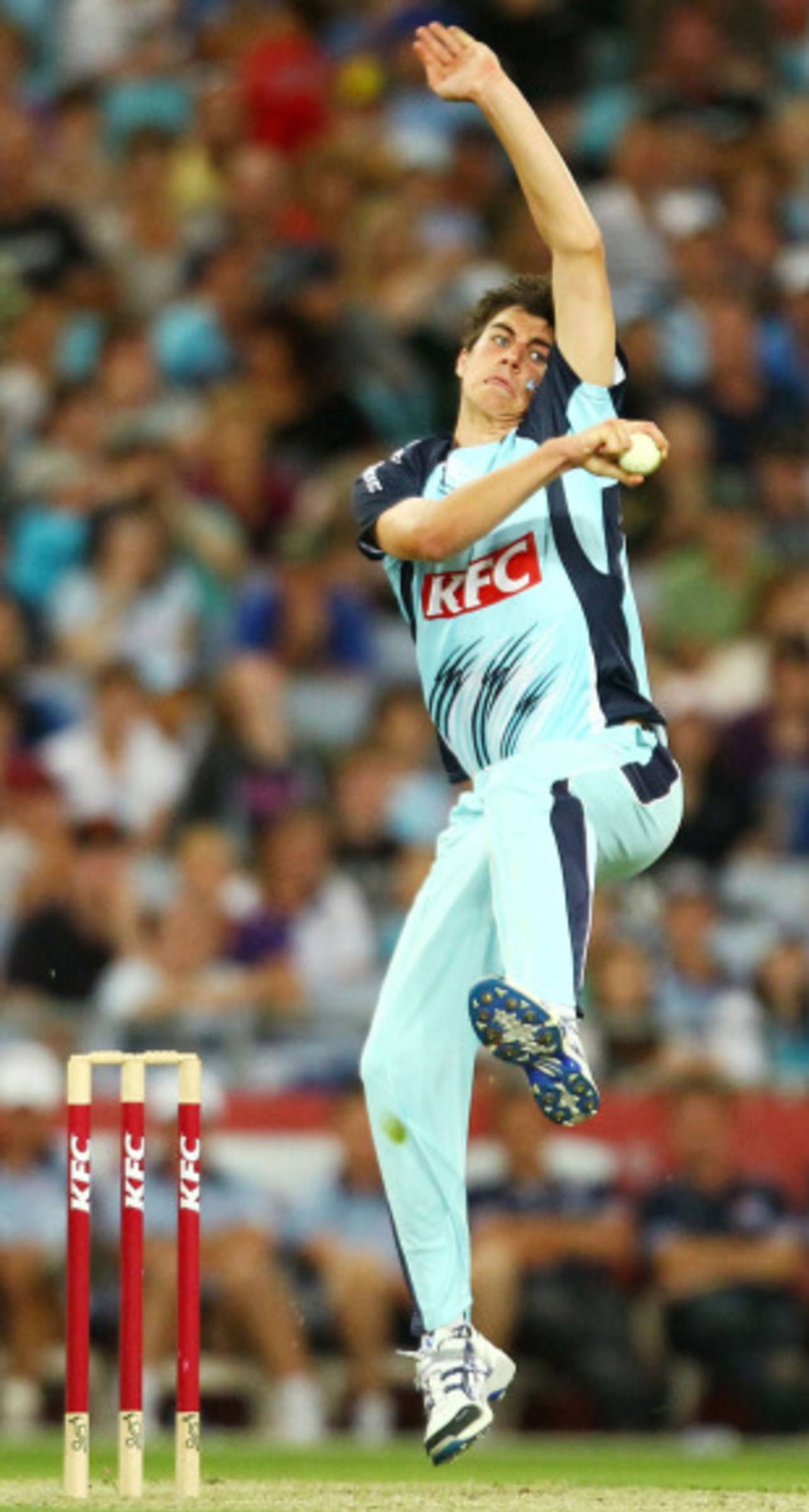

Most genuinely fast bowlers have a short shelf life, so they should be picked while they are still quick • Getty Images

It's not surprising young Patrick Cummins' arrival in the Australian team has created a lot of interest. Genuine fast bowlers are only slightly behind swing bowling and legspin as vital factors in cricket's success.

While swingers and leggies add to the variety of entertainment, the genuine fast bowler puts the test into Test match cricket. He tests the courage of batsmen, and whilst this has been diluted in the era of substantial protective equipment, any player who is the slightest bit apprehensive will still be found out. Nothing stirs the excitement of the crowd like the sight of a Brett Lee charging in off a long run to be confronted by a belligerent Virender Sehwag. The mystique surrounding the first ball of a Test match is built on such confrontations.

The fact that Cummins' hasty arrival has created such interest is proof of the need for genuine fast bowlers. That he's being hailed as a prospect, though he has very little prior history, is also an indication there aren't enough of his type in the game at the moment.

In the 1990s the game was blessed with a boatload of good fast bowlers: the obligatory four from the West Indies, the two Ws from Pakistan, and those in South Africa and Australia.

Currently there are good pace bowlers around, with Dale Steyn and Jimmy Anderson heading the cast. However, they rely more on swing to ambush the batsmen and don't create the same ripple of anticipation that buzzes around the ground when a genuine paceman measures out his run. There's nothing to match the thrill one feels at the sight of 60 metres of ground (40 of grass and 20 of turf) between the bowler and the wicketkeeper.

While there are concerns about the adverse effect Twenty20 might have on the technique and artistry of batting, a close watch also needs to be kept on what it does to fast bowlers. Already we are witnessing a variety of slower deliveries being paraded by the quicker bowlers. Consequently it's good to occasionally see a bowler like Shaun Tait, who works on this simple principle: "Here it is, see if you can hit it."

I once suggested to Jeff Thomson that he have a chat with his fast bowling team-mate Dennis Lillee about how to bowl on slower pitches. "Mate, if you don't mind," replied Thomson, "I'll do it my way." After some thought I realised Thommo was right; he was a fast bowler and he was going to live or die on his pace.

While a bowler needs to vary his pace in a fast-scoring game like T20, the wise words of former West Indies fast bowler Andy Roberts should be required learning for any budding quick. Roberts once asked: "Why don't fast bowlers change up instead of down?" That's how Roberts and a few other good quick bowlers operated; their pace variation was up a gear, and if it was well disguised, it was damned difficult to handle.

In picking 18-year-old Cummins, the Australian selectors have adhered to another of Roberts' pearls of wisdom. Roberts believed that fast bowlers only had a few years of genuine pace and it was important to "pick them while they're still quick".

It will be a pity if the hectic international scheduling leads to a reduction in the number of such fast bowlers. There aren't enough of them around now that the game can afford to turn those few who dream of bowling quick into medium-fast trundlers.

Fast bowling is a state of mind as much as a physical skill. Lillee once said: "As I stopped at the top of my mark, I imagined the ball still rising as it smacked into Rod Marsh's gloves."

Let's hope that Cummins and many other youngsters like him in every cricket-playing country are born with similar vivid imaginations. It takes a lot of courage to imagine that scenario when in reality what the bowler often sees in the distance is an armour-clad batsman standing at the end of 20 metres of lifeless turf.

Former Australia captain Ian Chappell is now a cricket commentator and columnist