Of unwritten laws and moral compasses

Cricket's relationship with its rules is a constantly evolving flirtation, unlike in golf, say, where things are more cut and dried

Jon Hotten

Apr 17, 2013, 8:19 AM

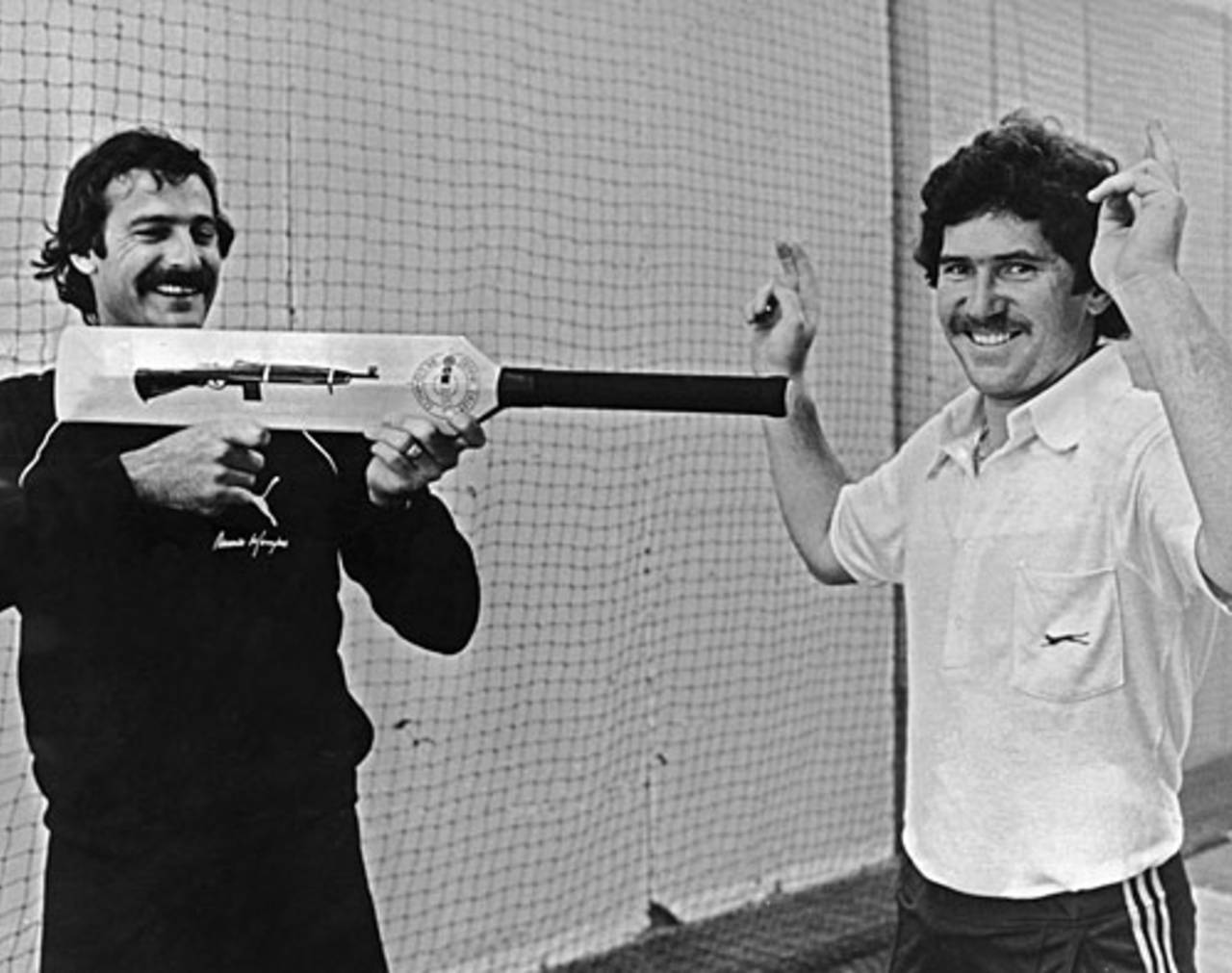

Dennis Lillee and his aluminium bat: legal but controversial • Adrian Murrell/Getty Images

In the first round of the 1925 US Open at the Worcester Country Club, Bobby Jones, then the best golfer in the world, was preparing to play his third shot from the rough around the 11th green when he inadvertently brushed the grass close to his ball and caused it to move. Only Jones was aware that it had happened but he immediately called a penalty on himself, added a shot to his final score and went on to lose the tournament in a playoff. When he was congratulated on his sportsmanship, Jones replied, "You might as well praise me for not robbing a bank."

For Bobby Jones, the rules were there for a reason, and they were implacable and unambiguous. He became the golfer upon whom the Masters tournament was founded. Glorious Augusta this year found itself embroiled in chaos of its own making: the 14-year-old Chinese wunderkind Tianlang Guan was docked a shot for slow play, a penalty that was last imposed almost 20 years ago, and the Tiger was lopped two, but not disqualified, for dropping his ball in the wrong place following an outrageous piece of ill fortune on the 15th green.

What was interesting was how the rulings exposed the powerful internal culture of the sport. Golf is policed not just by the officials, the other players and TV viewers watching at home (one of whom, it emerged, had phoned Augusta and dobbed Woods in), but by the competitor's own moral compass. And on the latter, everyone has an opinion.

It was of course irresistible to compare it to cricket, whose own founding father, that old rogue WG, enjoyed a somewhat different relationship with the laws of the game. "They've come to watch me bat, not you umpire…" ran his famous line, and his ability to cow officials into accepting his will travelled before him.

He was almost 50 when he engaged in battle with Charles Kortright of Essex, a bowler so fast he is said to have once bowled a bouncer that went for six byes. Grace had already created some bad feeling by claiming a catch from an obvious bump ball while fielding, and during his first-innings 126 had survived being caught and bowled by simply resuming his stance as if nothing had happened and then roaring an indignant "What?" at the umpire when he went to raise his finger.

In the second innings he had made 49 when Kortright roared in again. First Grace was struck on the pad, plumb in front: not out. He edged the next ball to the keeper and again held his ground, glaring down the pitch and daring the umpire to raise his finger. Kortright then found an unplayable one that uprooted middle and off. "Going already Doctor?" he asked. "There's still one stump standing."

No man, not even one as influential as Grace, can socialise an entire game, yet cricket has maintained an arbitrary and nuanced relationship with its laws, entangling them at times with an amorphous "spirit of cricket" that is intended to code certain types of behaviour. Bodyline, Trevor Chappell's underarm delivery, Dennis Lillee's aluminium bat, Vinoo Mankad running out Bill Brown while backing up: all were legal at the time they happened but all seemed to transgress unwritten rules, too.

When I was 13 or so, I spent what seemed like an entire winter studying the laws of the game because our club had entered a fortnightly quiz in which the first prize was some bit of equipment or other that I'd decided I couldn't live without. As we got through each round the questions became increasingly unlikely, based on speculative events like trees growing on the outfield, birds struck by the ball in flight and so on (the only one I remember clearly is, "What should the umpire do if the opening batsmen refuse to choose an end until the fielding captain says who is bowling?" I'd still like to know the answer to that.)

All of this had the unexpected side effect of developing a deep and irrational terror of the obscure ways of being dismissed. "Is it all right?" I'd almost screech before touching the ball if a defensive prod resulted in it dropping at my feet with no fielder around (Law 33 - out handled the ball). Waiting to go in, the bat and gloves would not leave my side (Law 31 - timed out). Was the standing umpire (usually someone's dad) fully conversant with Law 34 (hit the ball twice) and how it interacted with Law 37.1 (out obstructing the field)?

I've forgotten it all now, of course. Most players - and I suspect, most professionals - don't really know the laws, certainly in the way that a golfer has to know the rules of their game. But then golf has Bobby Jones as its ghostly conscience. WG is an altogether freer spirit, and cricket's relationship with its laws, which to the outsider might seem arcane and rigid, continues as a constantly evolving flirtation.