Classic cricket books aren't all ancient

The best cricket writing didn't end with Fingleton, Arlott and CLR James. Today's writers have tackled difficult topics the old masters couldn't

Suresh Menon

Nov 24, 2012, 3:12 AM

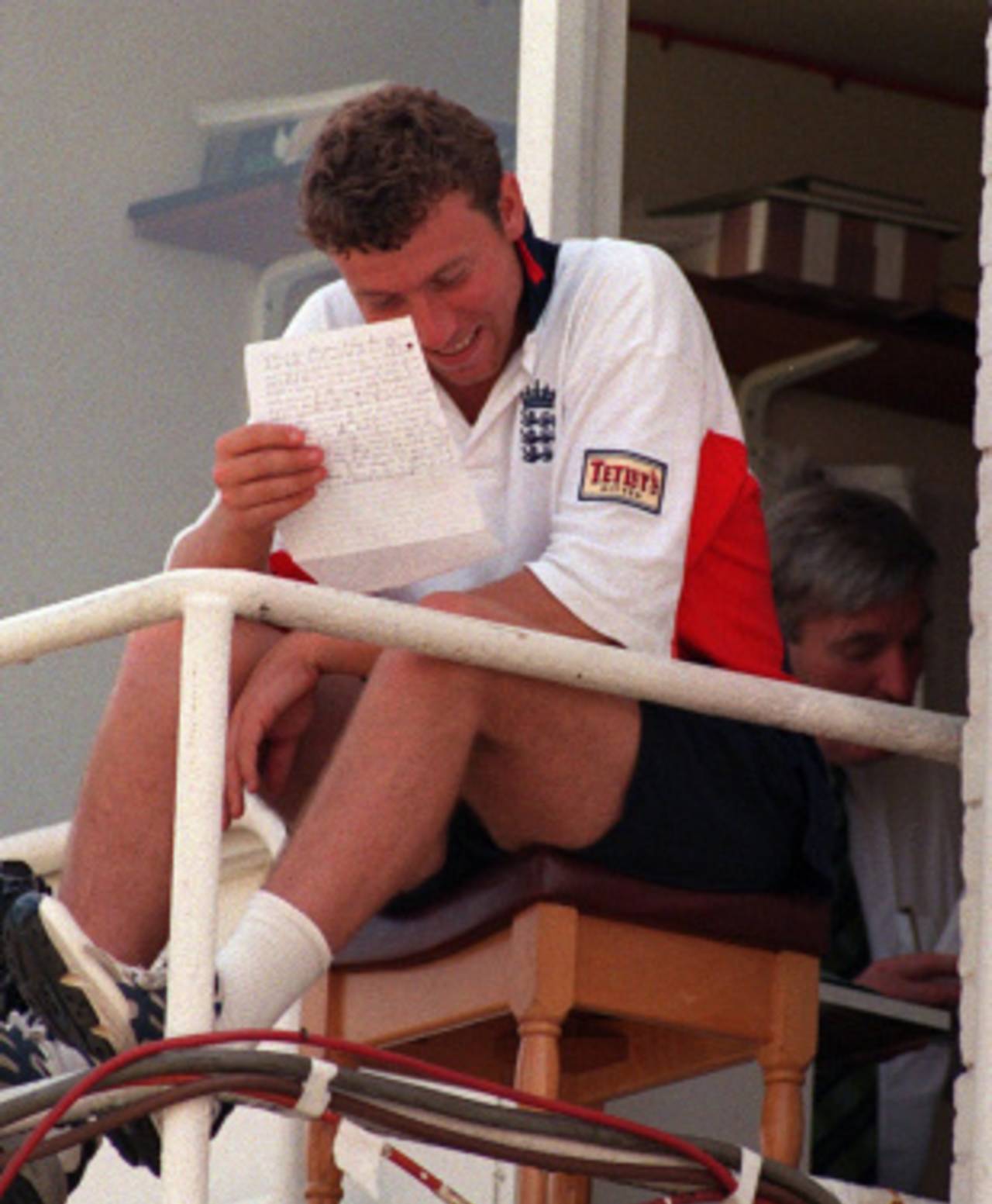

Mike Atherton's autobiography is one others cricketers would do well to emulate • Getty Images

First came the letters, then the phone calls (a nice reversal of the usual order of these things, say, 20 years ago). Why Fingleton? No good books since Robinson or Robertson-Glasgow? All wonderful writers, but what about the modern giants: have they no hope of being elevated to the Arlott-James-Cardus class till they have been gone for at least two decades? When ESPNcricinfo's editor commissioned pieces for The Jury's Out series on favourite cricket books, there was only one condition: keep Beyond a Boundary by CLR James out of the reckoning. The jury didn't need to go out to decide on that one: the finest book written on the game.

Fingleton died in 1981, James in 1989, Arlott in 1991. To imagine that cricket writing came to a standstill after that is an insult to the modern masters: David Frith, Gideon Haigh, Peter Roebuck, Mike Coward, Ramachandra Guha, Scyld Berry, Rahul Bhattacharya, Mike Atherton, Ed Smith, Frank Keating, Mike Marqusee, Lawrence Booth, Simon Barnes. (And a host of others I have inadvertently left out - thus ensuring fewer Christmas cards this year.)

So here's a list of books written after the passing of Arlott that have the twin virtues of being wonderful reads and are easily available (for that was the other grouse expressed by some: many of the books mentioned are out of print). The only rule I have followed is: no books that were already mentioned in the original series.

The autobiography is the form that gives cricket writing a bad name. Ghost-written, it veers between the desperately boring recitation of facts and figures and safe gossip that makes the headlines for a day or two and then is forgotten. Yet, even without that disclaimer, the best one in recent years, Opening Up, would have made the grade. Written by the player whose name appears on the cover, Mike Atherton, it is the story of the life and times of the university-educated modern player (a breed that is becoming increasingly rare as the cradle-to-the-pitch movement gains momentum) whose world view is engaging.

Ed Smith's On and Off the Field is not an autobiography but details a season in county cricket with the erudition and humour one has come to associate with his writings. It is an early effort, written before he decided to tackle more philosophical questions connected with sport.

Aakash Chopra's Out of the Blue, about the rise and rise of Rajasthan, who won the Ranji Trophy twice in a row, has been praised as the first subaltern view of Indian cricket, but it is more than that. Part autobiography, part biography, it is full of warmth and humour.

The biography is a rich vein mined by some of the finest writers of our time. It is not necessary that only books about great players make for great biography, as Gideon Haigh showed with books on Warwick Armstrong and Jack Iverson. The latter's story, in Mystery Spinner, is a manual on research and interpretation about one of the most interesting bowlers to have played the game (but not long enough or often enough). Haigh, whose biography of Shane Warne has just been released, answers the what and the how; more interestingly, he suggests the why. His wide range of interests ensures that he both lays out the dots and connects them in fascinating ways.

Of the two biographies he wrote of difficult subjects, David Foot's Wally Hammond: The Reason Why is, in the author's words, "an attempt to interpret the paradoxes and the darker mental caverns which dogged and distracted him". In The Tormented Genius of Cricket, Foot examines the life and death of Harold Gimblett, the Somerset and England batsman who took his own life. The theme of suicide is dealt with by David Frith in Silence of the Heart, one of the most thought-provoking books on the game. It asks the question "Does cricket actually attract the susceptible?"

The Big Questions have been asked thus. By Mike Marqusee in Anyone But England, the historical attitude of England to the colonies even long after the latter gained independence. It captures the early days of the waning of power and the arrival of India as the new kid on the block, providing context and perspective. Frith's Bodyline Autopsy revisits an old Test series and provides fresh glasses to view it through, while Simon Wilde's Caught has to be the starting point for all future books on the match-fixing scandal. The politics that led up to and followed the D'Oliveira affair are captured by Peter Oborne in Cricket and Conspiracy: The Untold Story, while the best exposition of another problem, depression, is handled with rare honesty by Marcus Trescothick in his Coming Back to Me. These are issues the Carduses and the Thomsons of another era did not get into at all.

But what of the madness of the game, the humour, the teams whose passion is not matched by their talent? Cricket, Lovely Cricket by Lawrence Booth is not strictly a book you will find on the humour shelves, for it is a serious book written with a lightness of touch that only the truly obsessed can bring to their calling. The subtitle says it all: "An Addict's Guide To The World's Most Exasperating Game".

Marcus Berkmann's Rain Men brings together obsession, resignation, frustration and a batting average that reads like a shoe size. "To be treated with the respect you aren't due is the dream of every talentless sportsman," says the author. And you can't argue with that.

That's it, then, a thoroughly incomplete and purely subjective list. Let the arguments begin.

Suresh Menon is the editor of Wisden India Almanack, and author, most recently of Bishan: Portrait of a Cricketer