The bespectacled army

A XI that may not have always seen the ball like a football, but would have done well nevertheless

Bill Ricquier

23-May-2014

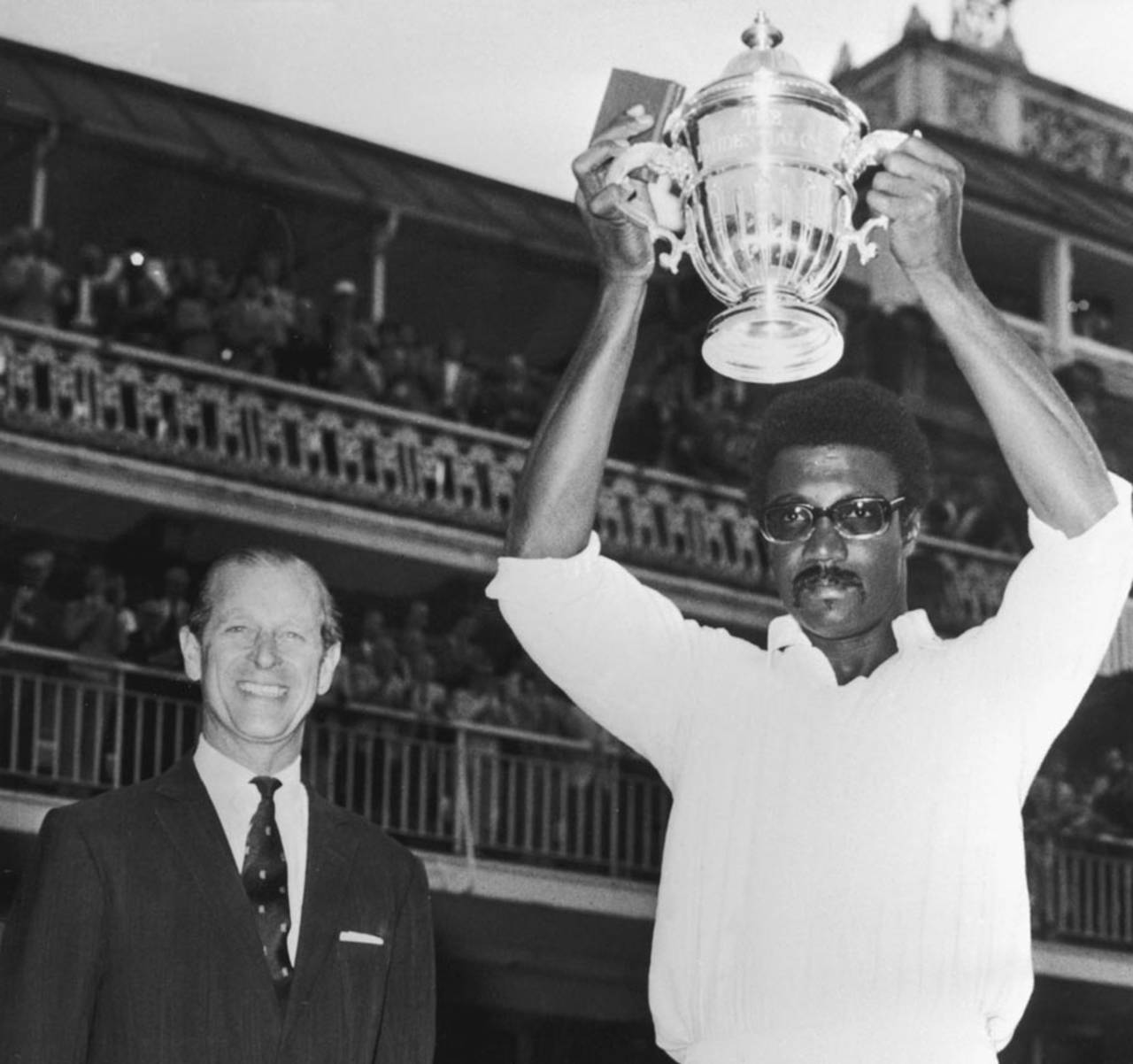

Clive Lloyd. Bespectacled. Spectacular. • Getty Images

Watching Virender Sehwag wearing spectacles in the IPL, made one think of Test cricketers over the years who have been similarly adorned. It is odd in a way, given the number of cricketing clichés suggesting the desirability of Twenty20 vision, that one can put together a highly competitive unit of the optically challenged.

There seems to be a belief in the blogosphere, particularly in Asia, that the great West Indian opener Gordon Greenidge wore glasses. Well, maybe he did, once in a while. All I can say is that, having watched him on numerous occasions playing for Hampshire from his debut season in 1970 to his last season in 1987, I never witnessed him wearing spectacles on the field. Either way, Greenidge was not a bespectacled cricketer; that is what we are talking about here.

The openers

Now, the openers (Virender Sehwag, like Greenidge, does not qualify as he has not played enough with glasses). They pick themselves - Roy Marshall and Geoffrey Boycott. Apart from the fact that they were both right-handers, one cannot imagine two more different batsmen, picking them to bat together is a bit like hosting an imaginary dinner party for Dorothy Parker and Gordon Brown.

Marshall, perhaps the greatest of all West Indian batsmen - enjoyed a stint with Hampshire after making a big impression on the West Indies' tour of England in 1950. He played very little Test cricket like his successor as Hampshire opener - Barry Richards. But, like Richards, there were fewer more enjoyable players to watch. Both exuded authority at the crease, but while Richards was grace and timing personified, Marshall had a power and flair that were typically Caribbean. His strengths were the front-foot drive and the square cut. In John Woodcock's 'One Hundred Greatest Cricketers', he said that if he had would select players purely for the pleasure they gave, Marshall would have made the list. I can testify to this, the feeling of disappointment when Marshall failed is something I have never quite sensed since.

To say that the feeling was exactly the opposite with Boycott would be unfair, but he could be a bit turgid. He wore glasses for the first six years or so of his professional career, switching to contact lenses after the 1968 season. One of his biographers, Leo McKinstry, says that this had a liberating impact on his batting. It is true that, like Bob Dylan, Boycott started old and got younger, at least up to a point. In 1967, he made a double-century against India and was dropped for slow scoring. Many believed that one of his most exciting innings ever was his memorable 146 for Yorkshire, in the Gillette Cup final against Surrey in 1965.

Reserves include Pankaj Roy and Anshuman Gaekwad.

The middle-order

Zaheer Abbas was a leading batsman for Pakistan for most of the 1970s and into the mid 1980s. He displayed a calmness at the crease that made him very easy on the eye. He made an immediate impact on his first tour of England in 1971, making 274 in the first Test at Edgbaston, and following it up with 240 at The Oval in 1974. He was prolific in first-class cricket, especially for Gloucestershire, and is the only batsman from the subcontinent to have scored 100 first-class centuries.

Mike Smith was another highly effective run-getter, principally for Warwickshire and England, from the late 1950s to the mid 1970s. He had a distinctive, open faced style and could smash anything that was even remotely loose. He led England with quiet authority in tours of India, South Africa and Australia in the mid 1960s. South African, Peter van de Merwe, was another bespectacled middle-order batsman, who was also the last man to represent England at both cricket and rugby union.

Clive Lloyd, was undoubtedly one of the most daunting opponents in the 1970s and early 1980s. Tall and powerful, he had a languid demeanour that did not give the sense of prowess, both as an attacking left-handed batsman and as a predatory cover fielder. But it was his ascent to the captaincy of West Indies in the mid 1970s that set him apart. A genuine father figure, he and his young brigade had to first endure the trauma of a 5-1 defeat to the Chappells. It was that defeat, however, which convinced Lloyd of the way forward, which was to use four fast bowlers. West Indies' dominance was unchallenged for a nine-year period starting from 1976 leading up to Viv Richards' ascension to captaincy in 1985.

Other middle-order batsmen include Dirk Welham and David Steele. The latter was distinct for his premature grey hair to go with his glasses, and he was also dubbed 'the bank clerk'.

The allrounders

The No. 6 spot goes to the indefatigable South African, Eddie Barlow. He played 30 Tests, averaging 45 with the bat and 34 with the ball. He was a solid and pugnacious batsman, and a tidy and resourceful medium-pace bowler. He was one of the stars of the series between the Rest of the World and England in 1970, staged to replace the cancelled South African tour. Barlow scored 353 runs at an average of almost 40, and took 20 wickets, including a hat-trick.

Jack Crawford was another terrific allrounder, who played for England and Surrey just before the Great War. He had been a cricketing sensation at Repton School, and played his first season for Surrey while still a schoolboy. He was England's youngest debutant before Brian Close, and although he had a rare talent as a hard-hitting batsman and fast bowler, other interests drew him away from cricket.

The wicketkeeper

Two leading wicketkeepers, Paul Downton and Mark Boucher suffered serious eye injuries, the latter's being career-ending. Dennis Gamsy played two Tests for South Africa against Australia in 1969-70. But my choice is Paul Gibb, a highly eccentric cricketer. He wore glasses for a large portion of his career and was England's wicketkeeper on several occasions. A Cambridge Blue, he opened the batting for Yorkshire and gained selection for the MCC tour of South Africa in 1938-39 when he scored two Test centuries, including one in the 'timeless Test' at Durban. He went to Australia with Wally Hammond's side in 1946-47, where he shared the wicketkeeping duties with Godfrey Evans. He then disappeared completely from view before returning to play for Essex in 1950. Gibb later became a first-class umpire.

Remember when Anil Kumble bowled with glasses?•Mike Hewitt/Getty Images

The bowlers

It is perhaps not surprising that there is a veritable cornucopia of bespectacled slow bowlers - Tommy Mitchell, the Derbyshire leg spinner, Geoff Cope and Eddie Hemmings, also from England, Dilip Doshi and Nirendra Hirwani of India and Murray Bennett of Australia.

Daniel Vettori turned himself into one of the most useful cricketers of modern times. An outstanding slow left-arm bowler, who took wickets with subtle variations of pace and flight, he also became an immovable object in the New Zealand lower-middle order. He was a match-winner in the limited-overs game.

Vettori is unusual among modern cricketers, in having persisted wearing spectacles. The great Indian spinner, Anil Kumble, is far more typical, having abandoned glasses quite early in his career. Kumble was quite different from his outstanding contemporaries - Shane Warne and Mushtaq Ahmed, who relied predominantly on big turning legbreaks. Although billed as a legspinner, Kumble dealt almost exclusively in subtly varied googlies and top-spinners. He finished up as Test cricket's third-highest wicket-taker.

An honourable mention has to go the Jamaican slow bowler, Alf Valentine. As a 19-year-old, Valentine helped the West Indies to their first victory over England in 1950. He started wearing glasses during that tour, no one realised he needed them until it was discovered that he could not read the scoreboard from the middle. Valentine remained a force throughout the 1950s, but he found his second tour of England in 1957 a challenge.

Not surprisingly, bespectacled pace bowlers are not quite so plentiful. But Bill Bowes, a strapping Yorkshireman, played a minor yet memorable role in the Bodyline series in 1932-33, when he bowled Don Bradman of the first ball of the second Test at Melbourne. He took over 1600 first-class wickets at an average of just over 16. He became a highly regarded cricket correspondent and his autobiography, Express Deliveries, is one of the best of its genre.

If you had to invent a bespectacled cricketer, it would be something like Devon Malcolm, although he too in time opted for contact lenses. Take him to the end of a long run-up, put a ball in his hand and point him in the general direction of the stumps and he could do some serious damage. Never was this seen to better effect, than at The Oval in 1994 when he demolished a strong South African batting order with 9 for 57. Sensitively handled, he could have performed like that more often.

If you have a submission for Inbox, send it to us here, with "Inbox" in the subject line