When substitution adds up

Had RP been fit to bowl the 23 overs sent down by Tendulkar, Sehwag and Ganguly, in addition to the four to which he was confined, his strike-rate suggests he might have taken three wickets

Rob Steen

25-Feb-2013

Getty Images

For some of us, the only sports that count, that really hit the spot, are strictly team affairs. Those that draw on the collective spirit and - however fleetingly, in however delusory a fashion - persuade us that, contrary to Maggie Thatcher’s wicked self-fulfilling assertion, there is still such a thing as society, as community.

Utopian and fanciful as it may sound, there is evidence to back up this theory. Why else are the biggest sporting audiences, in the flesh and on the couch, generally those for baseball, cricket and sundry football and rugby codes? And no, the exclusion of Formula 1 is not an oversight. When did you last attend a Grand Prix and hear mass chants of “Go on Ferrari!”? Or, for that matter, “Give us an M, give us a small c, give us an L, give us an A, give us an R, give us an E, give us an N - come on you McLarens!”? And don’t get me started on cycling.

Several things separate cricket from other team sports, most obviously its rubbery adaptability, its refreshing 19th-century languor and the way it is held up – with varying degrees of conviction and good cause, admittedly - as a model for considerate and proper behaviour. Sure, there’s plenty of verbal abuse, but how grateful we are that dissent, sin-bins, red cards and early baths have no place in its lexicon. How thankful we are that the most famously disgraceful misdeeds in an international – Javed Miandad threatening to decapitate the provocative and equally culpable Dennis Lillee, Colin Croft shoulder-barging an umpire – both occurred the best part of three decades ago.

Nevertheless, there is one aspect in which cricket ploughs its own furrow with reckless abandon, and without so much as a scintilla of a decent excuse. And no, I’m not talking about the lack of a universally understood drug policy, or even plastering players’ nicknames on the back of their shirts (Okay, the revelation that Adam Gilchrist is known as “Churchie” did tickle a bit). No, I’m referring to substitutions.

Pinch-hitters and relief pitchers have long been part of baseball. It is now more than 40 years since the mandarins of English soccer, eventually softening after a string of FA Cup finals ruined by sides being reduced to 10 fit players, bowed to the principles of commonsense and permitted the use of substitutes. Three years later, in 1969, international rugby union, whose only passable alibi had been its supposed “amateur” status, followed suit by adopting what was known, amusingly, as “the Australian dispensation rule”. Mind you, by way of distancing themselves from that grotty, profoundly oiky, round-ball nonsense, the rugger-buggers did insist on the term “replacements”, a distinction that persists to this day. And still cricket, the most time-consuming of games, stubbornly, crassly, resists.

Instances where an injury has affected the tide of a Test do not spring all that readily to mind, I confess. Those five “absent hurt” Indians at Sabina Park in 1976; Ray Illingworth and Don Bradman falling foul of the footholds while bowling at The Oval, in 1972 and 1938 respectively; Terry Alderman coming off second-best after rugby-tackling an invading “fan” at Perth in 1982; a be-slinged Colin Cowdrey padding gingerly down the Lord’s pavilion steps for that goose-bumping climax against Frank Worrell’s West Indies in 1963. By the same token, how many hundreds of times has a bowler bowled half-fit, or a batsman taken guard with a busted finger?

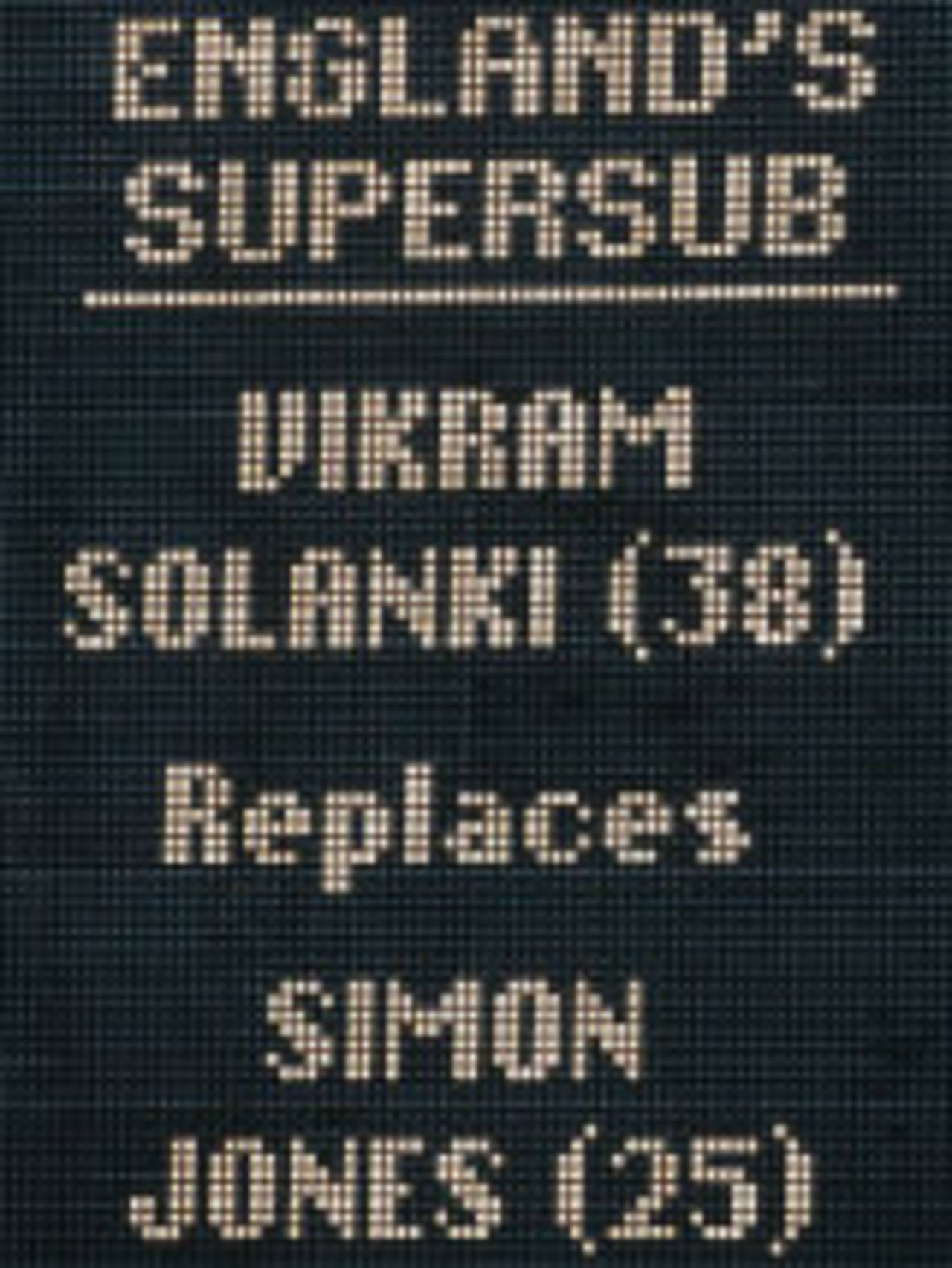

The irony is two-fold. For one, it is the shorter form of the game that has experimented with fully-fledged replacements. For another, cricket’s statutes are littered with references to substitutes. However, while the 12th man is a time-honoured concession – if only to the need for refreshment, glove changes and curt messages from skipper and/or bookie - it took centuries before he was even entitled to field in the slips. Only by special dispensation [the Anglo-New Zealand dispensation?] were Bob Taylor and Bobby Parks permitted to keep wicket in Bruce French’s stead at Lord’s in 1986. For heaven’s sake, even when the 12th man does manage to secure a scorecard entry, he is credited, merely, generically and demeaningly, as “sub”.

India were lucky in Adelaide last month. Having cocked a snook at fashion by picking five specialist bowlers, RP Singh’s early exit with hamstring problems was not the blow it might normally have been, but they did fail to secure a first-innings lead after exceeding 500. Had RP been fit to bowl the 23 overs sent down by Tendulkar, Sehwag and Ganguly, in addition to the four to which he was confined, his strike-rate suggests he might have taken three wickets. More importantly perhaps, while I do not know whether he would have been fit to bat in the second innings had he been required to do so (thank heavens for Sehwag!), the very idea that a team has to bat a man or more short in the event of injury offends all notions of fair play.

And yes, I can hear the harrumphing: what if players feign injury in order to allow tactical substitutions? Well, they shouldn’t have to. What, pray, is wrong with tactical substitutions? You don’t have to be Stephen Hawking to work out that, even in a non-contact sport, the longer a game lasts, the better the chance of 1) one or more players losing form; 2) the opposition’s form and tactics mocking your selection, or 3) the weather compelling a change of approach. Flexibility on this front can only make the game a better spectacle, rewarding quality rather than luck. It will also enhance the prospects for natural justice. Hands up those who crave neither.

So, please David Morgan, sir, make it one of your first orders of business, when you take over as ICC head honcho, to address this severe and blatant shortcoming. Stamp your foot if you wish, and bang a few heads together if you must, but I entreat you to do your level best to persuade your colleagues that teams should be entitled to select a squad of substitutes for every Test, with each member permitted to bat, bowl or even mind the stumps. You know it makes sense.

Besides, consider the wider context if we extend this principle to other realms of the game. Just imagine what difference a substitution might have made to one of the most controversial decisions of recent times. As soon as it became apparent, earlier this week, that Justice John Hansen, curiously, had not been fully apprised of Harbhajan Singh’s previous Code of Conduct breaches, he could have been whisked off and replaced by someone bearing less resemblance to a puppet.

Rob Steen is a sportswriter and senior lecturer in sports journalism at the University of Brighton